hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special series - part II] South Korea’s sinking shipbuilding industry

By Jeong Nam-ku, staff reporter

On April 11, 2011, the stock price of Hyundai Heavy Industries - South Korea’s largest shipbuilder - was 554,000 won (US$541.20) per share. On July 14, about three years and three months later, it had fallen to 163,500 won, less than a third of its former value.

This year, the stock prices of publicly traded shipbuilders have been trapped in a downward spiral. Through July 11, the shipbuilding index at the Korea Exchange had fallen by 31.1%, a bigger drop than any other business sector. Financial experts are even projecting that Hyundai Heavy Industries will post a loss for the year. Through May, the company had only managed to reach 30% (US$8.7 billion) of its new order goal for the year (US$29.4 billion). The situations at other shipbuilders are largely the same.

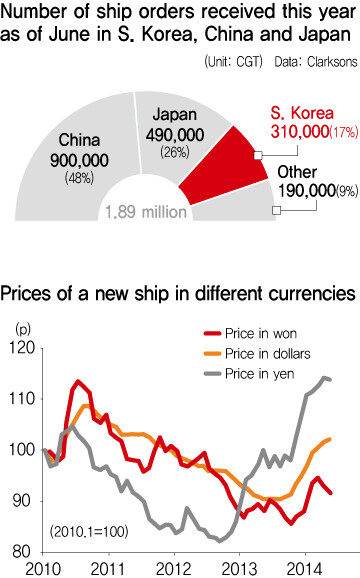

South Korea’s shipbuilding industry, which has been battling China for the top spot in ship orders, is in big trouble. According to data released at the beginning of July by Clarksons, an English firm that analyzes the shipping and shipbuilding industries, the ship orders received by Korean shipbuilders in the first half of 2014 amounted to 5.55 million CGT (compensated gross tonnage, an adjusted figure that reflects the difficulty of construction). This was only 61% of the 9.09 million CGT in orders received by Chinese firms during the same period.

[%%IMAGE2%%]In 2013, Korean companies received US$25 billion worth of orders for LNG carriers, which was US$4 billion ahead of China, but this year the value of orders is down to US$13.2 billion, US$1.3 billion behind China. China is effectively cornering orders for low-cost ships, such as bulk carriers and tankers.

Global shipbuilding capacity has improved greatly, but since the global financial crisis, fewer orders have been made for ships and ship prices have fallen. This drove the shipbuilding industry into a dire recession from which it is still struggling to escape. The number of shipyards worldwide has decreased from 629 in 2007 to 429 in May 2014, and industry analysts believe that the issue of excess facilities is being resolved to some extent. However, ship prices have yet to rebound.

Clarksons’ new shipbuilding price index approached 190 in 2008 before plunging to 126 in May 2013. Today, it has only recovered somewhat, hovering around 140. With the number of orders for ships decreasing, many analysts believe that it is unlikely that ship prices will recover any more in the future.

Worldwide ship orders made in the first half of the year were down about 17% from the previous year. Especially worrisome was the fact that the ship orders in the second quarter were at 54% of the first quarter figures.

“With ship orders decreasing around the world, most of the orders are going to inexpensive shipyards in China. Before long, new ship prices will start falling again,” said Yoo Jae-hoon, analyst with Woori Investment and Securities.

The weak Japanese yen and the strong South Korean won are making things harder for South Korean shipbuilders. Since 2010, a scary prediction made the rounds in the Japanese shipbuilding industry. Known as the “2014 Problem,” the story went like this: China sets up shipyards in various places, and global shipbuilding production capacity in 2011 was three times greater than 2001. Maritime shipping capacity doubles, but the amount of freight only increases by 50%. With ship orders dropping off after the global financial crisis, by 2014 there are no more ships for the Japanese industry to build.

But this prophecy turned out to be false. In 2013, ship orders for Japanese companies increased by 75.9% year on year, recording the highest figure in six years. While people were forwarding the scary tale, a great deal of restructuring took place in the industry, and the weak yen increased the price competitiveness of Japanese shipbuilders, sending their influence soaring. After the nuclear meltdown at Fukushima, Japanese companies ended up placing quite a few orders for LNG carriers, giving Japanese shipbuilders a shot in the arm.

According to data from Clarksons, Japan received 490,000 CGT in orders in June 2014, exceeding South Korea’s 310,000 CGT in orders. After April 2014, this was just the second month that South Korea fell behind Japan in monthly orders. The problem was that South Korean companies received hardly any orders for offshore plants - an area where they have a competitive advantage - while Japanese companies won bids for a slew of big container ships.

“Rather than making an effort to raise ship prices, Japanese shipbuilders are focusing more on redressing the order imbalance, which has taken a big hit because of the lack of orders over the past few years,” said Jeong Dong-ik, analyst with Hanwha Investment and Securities. This could slow the speed at which new ship prices rebound, Jeong believes.

“South Korean companies still retain a competitive edge in LNG carriers and ultra large container vessels,” said Hong Sung-in, chief shipbuilding researcher at the Korea Institute for Industrial Economics and Trade (KIET). Hong says that the South Korean industry is in trouble but that its competitiveness itself has not weakened substantially.

But prospects for an improvement in the industry remain dim. “With Chinese shipbuilders gradually increasing their competitiveness through government support, South Korea has to keep looking for a breakthrough, perhaps by increasing its competitive edge in high value added vessels,” Hong added.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 3‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 4[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 5Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 6[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 7[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 8[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 9Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 10Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?