hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Weak job market and encroaching AI cause headaches for young people

Two recent pieces of news surfaced to bring tears to the eyes of the so-called “2030 generation.” The first was that household income from this age group - people aged 20 to 39 - fell for the first time since statistics have been collected. The second is that the unemployment rate for people aged 15 to 29 stood at 12.9% last month, the highest since unemployment was first tallied by the same standard in 1999.

But there was something even more terrifying to the 2030s: the five-game “clash of the century” series of Go matches between grandmaster Lee Se-dol and the artificial intelligence program AlphaGo. AlphaGo’s win sparked growing fears that artificial intelligence could end up taking jobs away from people. If the income and unemployment figures testifying to the bleak reality facing 2030s today, then AlphaGo’s victory left them worrying about the future too.

Earned income decline now in full swing

Statistics Korea investigates household income factoring in four sources: labor, business, assets, and transfers. The Hankyoreh performed an analysis on Mar. 27 for 13 years’ worth of Statistics Korea trend surveys for nationwide households of two people or more. What emerged was slow growth in earned income, and rapid growth in transfer income. For the years under examination - 2003 to 2015 - earned income grew by an average annual rate of 4.8%. Transfer income grew almost twice as fast, by a rate of 8%. This means that income received from other individuals such as parents and children (private transfer income) or from national, basic, or other public pensions (public transfer income) is accounting for an increasing portion of household income - as opposed to income earned by working.

Earned income does of course still account for an overwhelming portion of income, at around 70%. But if trends of increase identified for different income sources over the past 12 years hold up - or strengthen - then a drop in its percentage seems to be a matter of time. The decline of earned income is becoming a reality.

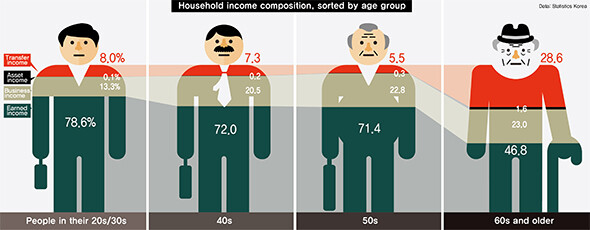

Who is likely to be hit hardest? The answer is people in their 20s and 30s, who depend more on earned income than other age groups. Last year, earned income accounted for 78.6% of ordinary income for households headed by someone aged 39 or younger. It’s a number almost 10 percentage points higher than the 69.1% average for all households. The portion of earned income out of all earnings declines for higher age groups, dipping to 72% for those aged 40-49 and 71.4% for those aged 50-59 before plummeting to 46.8% for those over the retirement age of 60. The decline in household income for the 2030s last year (13,808 won, or US$11.85) was the result of a steep drop in earned income (24,893 won, or US$21.36). People aged 20 to 39 have been the first casualties of the earned income decline phenomenon.

Job market turns its back on young people

The 2030 generation’s earned income decline has followed two paths. One is a lack of jobs as a source of income. The unemployment rate for people aged 15 to 29 stood at 9.2% last year, the highest level since statistics were first collected by the current standard in 2000.

More notable still is the gap between the youth and overall unemployment rates, which has grown steadily since the 2000s. Measured at just under four percentage points as recently as 2000-02, the gap widened to between 4 and 4.5 percentage points over the next ten years; in the past two years (2014 and 2015), it has leapt to around 5.5 percentage points. The numbers mean the pain of unemployment is disproportionately a problem for young people.

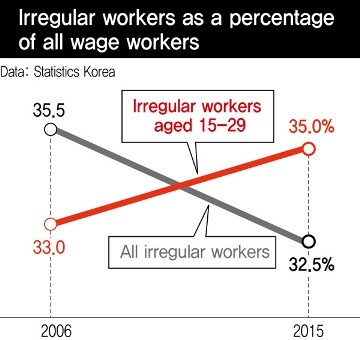

Another factor in the earned income slide is the fact that those who manage to make their way over the threshold are unlikely to find a decent job on the other side. Examination of Statistics Korea supplementary surveys on the economically active population between 2003 and 2015 showed the ratio of irregular work to wage labor positions growing only among young people over the past ten years. In 2006, 33 out of every 1000 positions among employed young people were irregular; by 2015, the number was up to 35. In contrast, the 30-39, 40-49, and 50-59 age groups showed declines of 8.5 positions, 8 positions, and 7.3 positions, respectively.

Why are young people being uniquely mistreated by the job market? One clue can be found in a 2009 pan-governmental campaign to slash wages for incoming company employees.

As the effects of the 2008 global financial crisis translated into job market instability, the government had the idea in 2009 to cut starting salaries for company employees and use the savings to hire more. The trend soon spread rapidly - not only to public enterprises and the financial world, where the government’s influence weighs especially heavily, but also to the 30-39 age group. It’s the reason an employee hired in 2009 or 2010 received 20% to 30% less in pay than a colleague doing similar work received as a new hire before 2009.

It also provides an example of how young people can become the easiest scapegoats when the job market is tough. The same situation has been replaying recently: as the unemployment rate rose once again, financial company user groups suggested starting salary cuts for new hires as a compromise with labor unions. Inside union walls, employees are entitled to protections - but young people either can’t find their way in or have little voice in the workplace.

The AlphaGo factor: the new threat of artificial intelligenceIn any attempt to explain why wages for workers in their 20s and 30s are shrinking, one factor that is always mentioned is the advance of technology. Newly appearing technology has transformed the industrial landscape, and along the way the employment market has undergone tremendous changes.

New technology is having a particularly major effect on the jobs of people in their 20s and 30s. The fact is that, when managers need to downsize, it is much easier to reduce the number of new hires, since these are not protected by labor law and unions.

Such developments can be confirmed in the employment markets of advanced countries, in which technological innovation has proceeded faster than in South Korea.

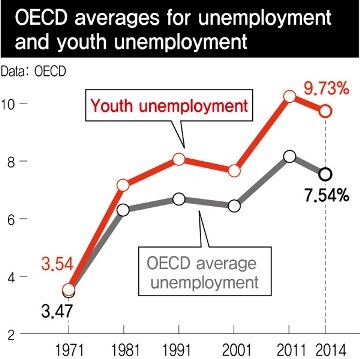

The unemployment statistics for OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) member countries between 1971 and 2014 show that, in the 1970s, unemployment in the total population and unemployment among the youth was virtually the same (0.386% and 0.393%), with just a 0.007 percentage point difference between them. This gap increased to 1.14 percentage points in the 1980s and 1.52 percentage points in the 1990s. Since the 2000s, it has widened still further to 1.71 percentage points.

The match held at the beginning of this month between Lee Se-dol and AlphaGo revealed the groundbreaking progress that has been made in artificial intelligence (AI).

During the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, just a few months ago, the emergence of AI was even heralded as the “Fourth Industrial Revolution.” This suggests that AI‘s economic effect will be comparable to or greater than the steam engine in the First Industrial Revolution, electricity and mass production in the Second Industrial Revolution and computers in the Third Industrial Revolution.

One prediction made during the forum was that AI would result in the disappearance of five million jobs in five years.

Just as with past technological innovation, AI is very likely to threaten the jobs of people in their 20s and 30s.

“During the age of artificial intelligence, the economically active population will shrink, consumption will decrease and the concentration of wealth will become even more severe. Before long, unemployment will rise above 30%, increasing social conflict and instability. We need to be thinking about how to resolve such conflict,” said Lee Gwang-hyeong, a professor of bioengineering and brain engineering at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST).

Beyond increasing jobs for young peopleGovernment policy intended to counteract the drop in wages for workers in their 20s and 30s for the most part is concentrated on finding jobs for young people. The approach taken by the current administration involves introducing a “peak wages” system so that companies can use the money they save to hire new employees.

Whereas the administration of former president Lee Myung-bak (2008-2013) slashed wages for new employees, the Park administration has done the same with middle-aged workers.

Those who are critical of government policy may have different methodology, but their goals are the same. Advocacy groups that call on companies to use their cash reserves to increase investment and hiring want to fund youth employment by taking money from corporate coffers instead of from workers’ pockets.

To be sure, a variety of efforts are needed to increase youth employment. But considering that the issue of jobs for young people and the related decline in workers’ wages has been underway in South Korea for at least 10 years and in advanced economies for decades, such efforts do not appear to be a permanent solution.

In particular, they do not take into account the destruction of jobs that is brought about by technological development. This is why job programs should be accompanied by other measures that can compensate for the limitations of such programs.

One idea that has been proposed as a possible solution to this problem is a youth allowance. The idea is that, instead of focusing solely on increasing workers’ wages, income redistribution could be increased as a way to raise household incomes for people in their 20s and 30s.

In his book “Inequality: What Can Be Done?” Anthony Atkinson, a professor at the London School of Economics and an authority in research into inequality, explains a youth allowance as a kind of “basic capital” or “social inheritance.”

Atkinson emphasizes that a youth allowance could serve as seed money to shore up workers’ wages, which have declined from past levels due to unemployment and unstable jobs, and that such an allowance would be publically funded through taxes and not privately funded through gifts and inheritance from parents.

The youth allowance proposed by Atkinson is 10,000 pounds, which is about US$14,130.

By Kim Kyung-rok, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1Samsung subcontractor worker commits suicide from work stress

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 4No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 5Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 6N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 7Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 8US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 9[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 10[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon