hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Shipping industry is sinking, and it may be the wives’ fault

The South Korean shipping industry is on the verge of going under, and it blames its current financial difficulties on external factors, including a downturn in the global shipping industry. But internal management failure may have been an even more devastating factor. The industry may have brought the crisis on itself by allowing group chairmen’ wives to become chairs of the board of directors after their husbands’ death without assessing their management ability, to employ a dictatorial management style dependent on close associates and to indulge in a variety of dubious practices aimed at lining their own pockets.

Hyundai Group Chairwoman Hyun Jeong-eun is regarded as a prime example of this. When former Hyundai Group chairman Chung Mong-hun committed suicide during an investigation into his connection with a transfer of funds to North Korea in 2003, Hyun was appointed chairwoman in his stead.

But at that point, Hyun had no management experience. While some both inside and outside the group called for the selection of a skilled professional manager and the adoption of a system that would separate ownership and management, Hyun insisted on maintaining the owner-management system.

“Shipping is a business that requires sophisticated management expertise about trends in the global economy; changes in oil prices, have a significant effect on revenue; knowledge about how to finance ship construction; and strategic judgment for chartering ships, since contracts can last as long as 20 years. This kind of management is hard for a beginner,” a former executive at Hyundai Merchant Marine said on Apr. 27.

Since Hyun knew little about management, she ought to have taken advantage of more experienced professional managers, but she did just the opposite.

“A president of Hyundai Logistics surnamed Park was replaced just one year after being appointed because he was reluctant to provide a payment guarantee to secure the outside funding needed to acquire Hyundai Engineering and Construction in 2009,” said a former executive at the Hyundai Group. “A president of Hyundai Merchant Marine surnamed Noh was one of the top professional managers who had assisted former chairman Chung Ju-yung, but he had to step down because he was said to be too close to segments of the group who were squabbling over the management rights.”

From the time that the shipping industry entered a downturn in 2010 until last year, a total of six people had served as head of Hyundai Merchant Marine, with an average tenure of just one and a half years. The Hyundai Group explained the churn as the consequence of presidents being held accountable for their poor performance.

Since Hyun became chairwoman, all the advertising work for its affiliates has gone to ISMG Korea. After it turned out that company president Hwang Du-yeon had embezzled more than 10 billion won (US$8.8 million) from the company for several years, he was given a three-year prison sentence (suspended for four years) in 2014, but Hyundai is still doing business with the company.

While it is unusual enough for a huge chaebol like Hyundai to provide all of its advertising assignments for more than a decade to a small company, what is even stranger is the fact that it has continued to do so even after that company’s president was convicted of illegal behavior.

The reason for this, according to a former executive at the Hyundai Group, is Hwang’s close ties with Hyun, the chairwoman. “Even though Hwang doesn’t have any official title at Hyundai, he controls the management of the group and behaves like he’s the number two at the group,” the former executive said.

The labor union at Hyundai Securities made a big splash in 2012 when it released a transcript of recordings showing that Hwang had called presidents of group affiliates into his own office to receive reports and to give instructions. Hyundai Group responded by describing the people who had gone to Hwang’s office as being not company presidents but other executives.

Allegations that were raised when the prosecutors were about to investigate Hwang – which concerned his improper involvement in the merger of Hyundai Securities with Hyundai Savings Bank and his creation of a slush fund during the construction of the training institute for the Hyundai Group – were just the tip of the iceberg.

“It’s widely rumored in the group that Hwang was involved in acquiring the Banyan Tree Club and Spa Seoul for 160 billion won in 2012, when it was already starting to struggle financially, and that he was pocketing money not just from advertising but from a variety of business opportunities at the group, including building and parking lot maintenance; supplying office materials; and supplying the gas, food and parts needed on ships,” said a former executive at Hyundai Merchant Marine. “In 2009, Hyundai Global acquired a 40% share of ISMG Korea, and 100% of stock in Hyundai Global is held by Hyun’s family.”

When Hyundai Heavy Industries and KCC Corporation started squabbling over management rights after purchasing shares in Hyundai Merchant Marine, Hyun used Hyundai Elevator Company, a group affiliate, to sign a derivative contract with investors both in South Korea and other countries. This contract guaranteed that those investors would receive high profits even if the company’s stock price fell – as long as they promised to side with Hyun when they exercised their voting rights.

Ultimately, Hyundai Merchant Marine’s stock price plummeted, causing hundreds of billions of won in losses for Hyundai Elevator Company and causing Schindler, the second-largest stockholder, to file a lawsuit for damages that is still in the courts.

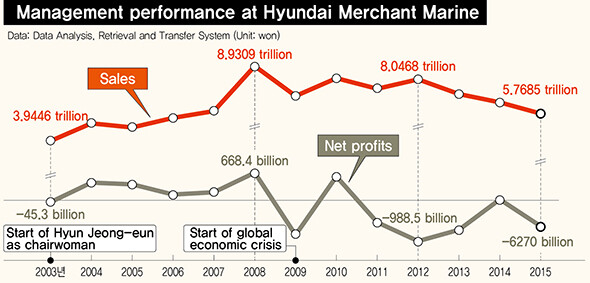

It is not as if Hyundai Merchant Marine has had no opportunities since Hyun became chairwoman. Between 2003, when Hyun became chairwoman, and 2008, just before the global financial crisis, a boom in the shipping industry helped the company make 2.3 trillion won in operating profits and 1.8 trillion won in net profits.

“At the time, our rivals in other countries were placing orders for extra-large ships to increase their competitiveness, but Hyun was focusing her efforts on cutting costs and streamlining the company instead of investing in the future,” said a former executive at Hyundai Merchant Marine. “She brought this crisis upon herself by getting involved in building a new training center for the group, acquiring the Banyan Tree hotel on Namsan and then jumping into the struggle to acquire Hyundai Engineering and Construction even after conditions started to worsen in the global shipping industry in 2010.”

A spokesperson for the Hyundai Group acknowledged that it had missed the boat by not ordering large ships in the mid-2000s but argued that this was not entirely Hyundai’s fault. “The government’s regulation of our debt ratio was one obstacle to investment. Plus, the Export-Import Bank of Korea was no friend of Hyundai Merchant Marine’s when it provided ship financing to overseas competitors at a lower interest rate than it would give us, provided that those competitors ordered their ships from Korean shipyards,” the spokesperson said.

The story of Choi Eun-yeong, former chairwoman of Hanjin Shipping, played out in a similar manner to Hyun’s. After the death of Cho Soo-ho, her husband and former chairman, Choi took over the helm herself in 2007. But she did not have any previous experience in management, either.

Choi came under fire when it was revealed that she and her children had sold all of their shares in Hanjin Shipping just before the company petitioned its creditors for help in restructuring.

Hyun was paid a huge amount last year - 4.53 billion won (a little less than US$4 million) altogether – from Hyundai Merchant Marine, Hyundai Elevator Company and Hyundai Securities, despite the financial problems they face. This is triple the 1.59 billion won that she received one year before.

Behind the catastrophe of countless workers losing their jobs when struggling corporations undergo restructuring is the problem of chaebol owners being responsible for managing their companies.

“The greatest vulnerability of South Korea’s chaebol system is the inadequacy of oversight and checks and balances inside the company to correct for poor decisions by incompetent owners, which weakens the group as a whole. Again and again, this cost must be borne by the national economy,” said Kim Sang-jo, director of Solidarity for Economic Reform. “We need institutional investors like Korea’s National Pension Service to become activist shareholders, and we need the commercial code to be revised to require the appointment of independent external directors.”

By Kwak Jung-soo, business correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 3[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 4Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 5Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 6N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 7[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 8[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 9Kim Jong-un expressed ‘satisfaction’ with nuclear counterstrike drill directed at South

- 10[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent