hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Is “sales diplomacy” really just an empty slogan?

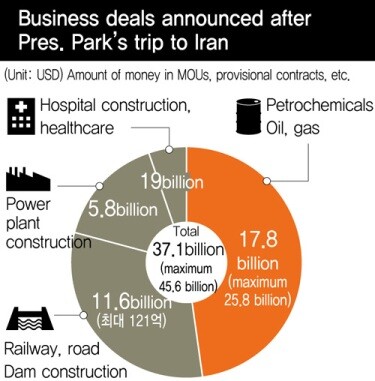

The term “sales diplomacy” is frequently attached to presidential visits overseas. The idea is that meetings between leaders lead to increased overseas opportunities for South Korean businesses. This is what happened when President Park Geun-hye visited Iran on May 2: the Blue House announced that the visit had “laid a stepping stone for 52 trillion won [US$45.6 billion] in infrastructure building and energy reconstruction project orders,” while news outlets trumpeted the “52 trillion won jackpot” and “big sales diplomacy win.”

In contrast, local media in Iran emphasized only the investment aspect, noting the South Korean pledge to invest in infrastructure efforts. The picture they painted - South Korea agreeing to put money toward certain projects - was quite different from the “orders” claimed by the South Korean government and media.

Experts have also been cautious, noting the time needed for those orders from South Korean companies to before a reality and stressing that the profitability will only become clear in the future. Many in the construction industry have stressed the many obstacles to actual orders happening. Why the difference in tone?

Perhaps the most significant fact is that South Korean export financing institutions would have to put forward US$25 billion (around 29 trillion won). Korea Exim Bank has agreed to offer US$15 billion (17.7 trillion won) in loans and guarantees, with another US$6 billion (7 trillion won) in guarantees from the Korea Trade Insurance Corporation (KTIC) and the remaining support covered by the Korea Development Bank (KDB) and Korea Investment Corporation (KIC). In other words, state-run banks would be covering most of the costs for South Korean companies to undertake projects in Iran - since the Iranian government doesn’t have the money for it.

Of the US$15 billion provided by Korea Exim Bank, some US$9 billion is to take the form of loans to commercial banks in Iran for funding of efforts commissioned by different Iranian agencies. Another US$4.5 billion from Korea Exim Bank and the US$6 billion from KTIC is to be used for project financing (PF): provided as loans to special purpose companies (SPCs) established by South Korean businesses or as guarantees on loans taken out by those companies at banks in South Korea and overseas. Interest on loans and surety commissions would be covered by Korea Exim Bank or KTIC.

Coming up with US$25 billion is difficult enough, but it is not the end. Many barriers remain to be cleared before the actual efforts can begin. According to Korea Exim Bank, Iran has agreed to provide just 15% of total project costs, with the remaining 85% to be procured by South Korean businesses or financial institutions. Iran also stipulated that 50% of total project expenses must be spent on facilities or workers at its own construction companies. The problem in this case is that the OECD’s Export Credit Arrangement permits loans and guarantees of up to 115% only on project costs that do not include spending to local businesses by export credit agencies (ECAs) like Korea Exim Bank.

With 50% of total project costs going to Iranian businesses, this means financial support is only possible for up to 115% of the remaining 50%, or 57.5% of the total. This results in turn in a 27.5% gap between the 85% share of costs that the Iranian government is demanding and the 57.5% in permissible support funds allowed by the Export Credit Arrangement. In the case of a US$10 billion project, this would mean US$2.75 billion of the costs would have to come from a third party.

“We‘re trying to explain to the Iranian government right now that its demand that half the total project costs go to hiring local workers is incompatible with a framework where South Korea bears 85% of costs,” said a Korea Exim Bank source.

“We’re looking to whether it would be possible to obtain funds from the European Central Bank (ECB) or a multilateral development bank (MDB),” the source added.

Further complicating the attempt to find funds is the fact that sanctions on the use of US dollars in Iran have yet to be lifted. This complex set of problems would have to be resolved before any orders could actually come to pass.

Examples of project difficulties as a result of these problems are not hard to find. One is the building of the Balkhash coal-fired electrical power plant in Kazakhstan. In 2011, then-South Korean President Lee Myung-bak paid a visit and announced US$4.8 billion (5.6 trillion won) in orders; in 2014, President Park Geun-hye publicized the signing of a purchasing agreement for power from the project. Blue House Senior Secretary for Economic Affairs Ahn Jong-beom cited the Balkhash project - at a scale of US$18.8 billion (22 trillion won) - as a leading example of the US$67.5 billion (79 trillion won) in major projects won through “sales diplomacy” since Park took office.

But just a month after Ahn’s self-congratulation, construction had been halted. Samsung C&T suspended its efforts after frictions with the local government resulted in the cancellation of financial support initially pledged by Korea Exim Bank and KTIC. If construction does not resume, the company could end up losing around 200 billion won (US$168 million) in investments in the project.

“The project costs for the construction order came out to US$4.8 billion, and there have been differences in opinion on the guarantees between financial institutions in South Korea and the government there [in Kazakhstan],” explained a construction company source. On May 17, Korea Exim Bank staffers headed to Kazakhstan to resolve the issue.

Even if the projects do come to pass, it may take a long time for domestic companies or financial institutions to see a profit. Payback periods for profits on hospital, railroad, and highway infrastructure projects in Iran are set at 10 to 15 years.

“Saudi Arabia has used its own money for orders, but Iran doesn’t have money, so the agreement was for the investors to recover profits by operating highways and hospitals after their completion,” explained an official with the International Contractors Association of Korea.

“Some of the projects could require as long as 30 years to turn a profit, so we need to take a long view when assessing them,” the official said.

Another possibility that cannot be ruled out is a change in the Iranian political situation that makes profit recovery impossible.

The OECD has assigned Iran a country risk classification seven on a scale from zero to seven, indicating its lowest level of creditworthiness.

By Lee Jeong-hun, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 3Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 4After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 5[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 6[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 7Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 8US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 9Constitutional Court rules to disband left-wing Unified Progressive Party

- 10Nearly 1 in 5 N. Korean defectors say they regret coming to S. Korea