hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

A Hankyoreh reporter’s adventure with a 3D printer

When Han Gwang-hyeon, senior analyst at Today Maker, told me that he had made his own 3D printer, I could hardly believe my ears. Aligned with the DIY, or do it yourself, movement, Today Maker is an organization that works with communities and helps young people support themselves and find housing.

I asked, “What did you say? You made a 3D printer? You don’t mean you made something using a 3D printer?” Each time I repeated my question to Han he only responded by saying, “That’s right.”

3D printers are a new technology that has been drawing interest recently. I was dumbfounded to learn that such a high-tech item has been created at Today Maker.

But the next thing Han told me was even more astounding. He said that Today Maker was getting ready to offer a public lecture on how to make a 3D printer for materials that only cost 200,000 won (US$174). So I went to the class.

The first class for making a 3D printer was held at Seoul’s Social Economy Support Center on Apr. 18. On that day, fourteen students (including myself) joined the instructor - Kang Dong-ho, a researcher at Today Maker - to make a 3D printer.

“A 3D printer is not high-tech,” Kang declared on that first day of class.

“The fact is, all the really high-tech stuff is in the software. A 3D printer is just a machine that moves along the X, Y and Z axes according to commands from the computer.”

The software and designs - which are indeed cutting-edge - have already gotten into the hands of countless people, as tends to happen in this digital world in which nothing distinguishes copies from the original.

This was made possible by the RepRap project, which Adrian Bowyer, an academic from the UK, has been running since 2004. Sure enough, my class made a 3D printer using a design for a model called Smartrap Mini that had been uploaded by RepRap.

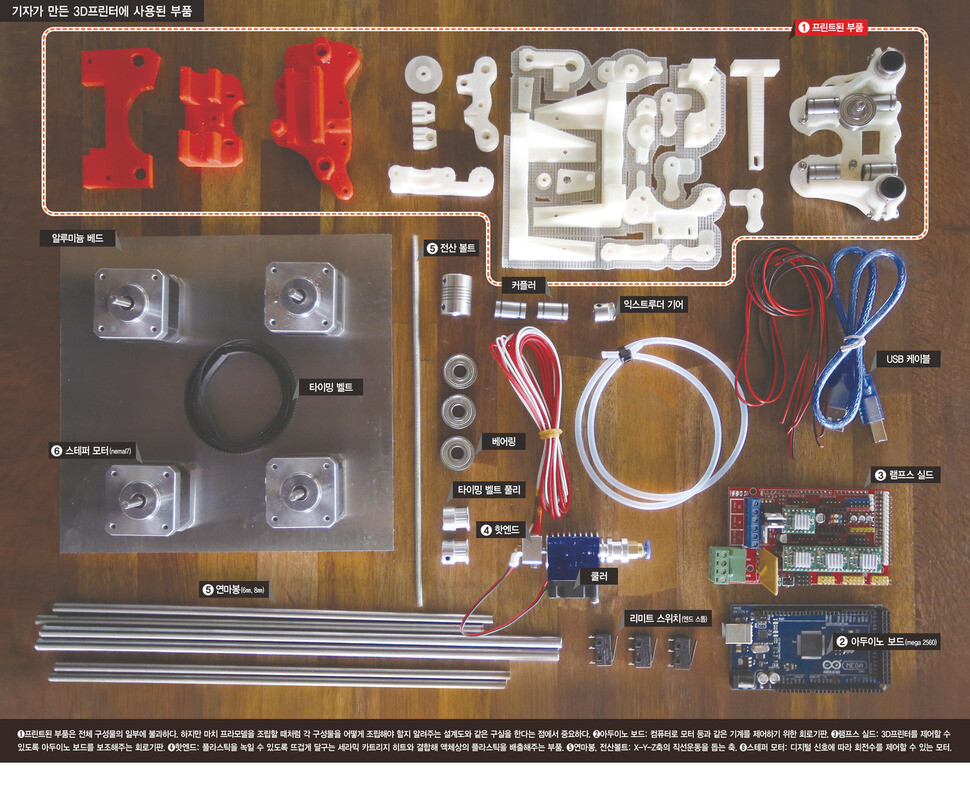

First, we went online to make some purchases: a stepper motor, which rotates in discrete steps according to an electric signal; the hot end, which melts the filament and extrudes it gradually; a 6 to 8mm metal rod and full thread bolt, which serve as the spindle that moves the hot end in a straight line on the X, Y, and Z axes; and a ball bearing.

Including the price of the parts we bought ourselves, it added up to about 150,000 won (US$130). There are also kits including all these separate parts that are sold for between 380,000 and 390,000 won.

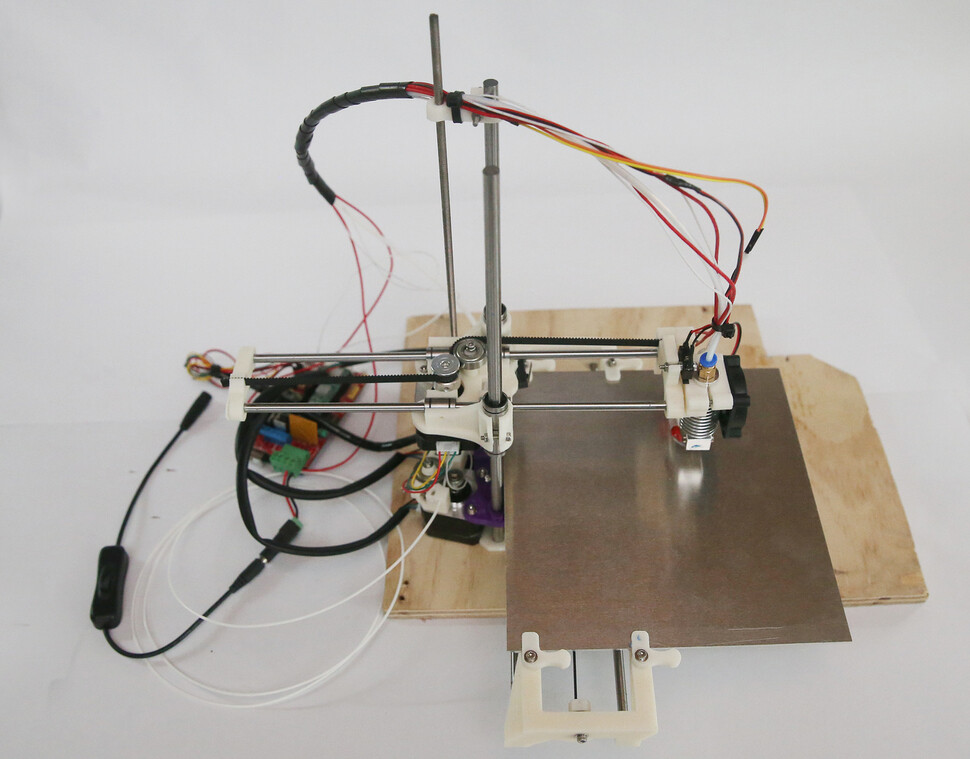

We assembled the parts we had purchased using “printed parts” that we made on a 3D printer at the Social Economy Support Center.

These printed parts functioned as a kind of blueprint. Just as you don‘t have to read the manual when putting together a model kit, the framework of the device took shape as we lined the motor, the metal rod and the full thread bolt up with the holes and angles on the printed parts.

Adding up all the work time, printing out the parts took 12 hours, and assembling them took between 4 and 5 hours.

Admittedly, it was complicated to hook up the Arduino board (a printed circuit board that sends computer signals to the device) and set up the computer interface. Even so, it’s no exaggeration to say that the entire assembly process involved little more than ensuring that the plastic on the spindle wasn‘t warped (since this would interfere with straight-line motion). What reason could there be for calling such a simple machine high tech?

The fact is that 3D Printing is an old technology - it was developed in 1984. While it has been steadily used as a tool for creating product models and prototypes, no one thought about using it for other purposes.

But the establishment of the RepRap project in 2004 and the expiration of a patent on material extrusion, or FDM, in 2009 created a favorable environment for new ventures.

Since then, there has been an avalanche of products for personal use. MakerBot, which has recently been a popular item in the US, Ultimaker in the Netherlands and Open Creators in South Korea are all examples of personal-use 3D printers based on the RepRap project that have been put on the market.

The fact that 3D printing technology has started to be picked up in a number of previously unrelated fields has also spurred innovation.

Products have been developed that represent a break with the past, such as motorcycles with remarkably lightweight frames that take advantage of the ease with which 3D printers can make complicated structures. And the medical world has started releasing products that are tailor-made to meet the needs of individuals.

Moving to outer space, efforts are underway to create space stations using the raw materials on the moon or on Mars.

As Clay Shirky argued in his book “Cognitive Surplus: How Technology Makes Consumers into Collaborators,” the fact that various people have an opportunity to turn each of their ideas into actual products itself is a seedbed for innovation. A large number of people often have better ideas than a small number of experts.

Described by the term “crowdsourcing,” this phenomenon is changing South Korean society.

NASA solved a conundrum related to solar particles that it had been struggling with for 35 years by putting it before the public. The person who solved the problem was not an astrophysicist, but a retired radio frequency technician.

“The reason 3D printers are considered an icon of innovation is because having easy access to 3D printers gives us a chance to imagine the possibility of things that many people have said were impossible,” said Moon Myeong-un, director of the Computational Science Center at the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST).

At the end of 1982, Time Magazine selected the personal computer as the machine of the year. Computers have made it easier to learn about various trends and to listen to music. Through spreadsheet software, they have even enabled us to perform data analysis that was previously impossible.

But since a 3D printer is able to copy objects, it could bring about even bigger changes. On YouTube, you can already watch a cheap saxophone being created on a 3D printer.

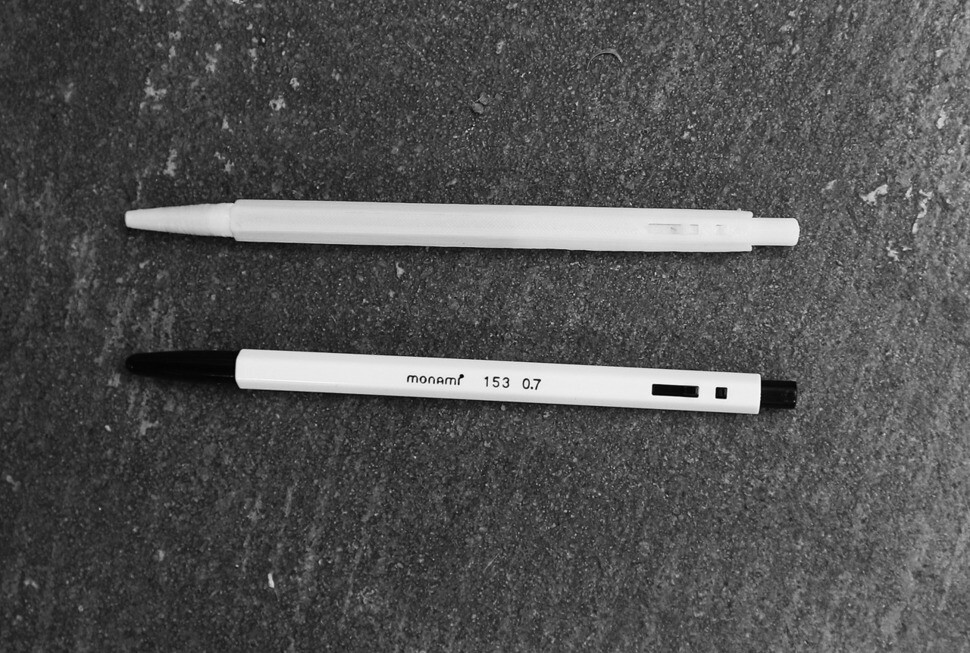

Using our handmade 3D printer, the Hankyoreh sat down with Kang and Shin Ji-ye, president of Today Maker, in an attempt to make a Monami 153 ballpoint pen. The reason we selected a Monami pen is because it encapsulates the historical sea change that resulted from the spread of Fordism, which is symbolized by mechanization, the division of the labor and the conveyer belt. When the Monami pen was first released in 1963, it was a valuable item to be treasured; today, it is a throwaway item. We wanted a chance to reflect on what we’ve lost along the way.

During our discussion, we decided to only copy the shell of the pen and not the refill, concluding that it would be basically impossible to create the ball at the end of the pen.

We modeled each part after measuring them with a caliper and then printed them on the printer. Aside from the time spend modeling and on trial and error, it only took 35 minutes to print the pen.

Printing the pen consumed about 9g of filament. Considering that 1kg of filament costs between 15,000 and 20,000 won, the pen was basically free in terms of material cost (omitting the cost of electricity).

But it wasn‘t easy to perfectly replicate even the simple shape of a Monami 153 ballpoint pen on a 3D printer. That’s because the pen is optimized for traditional manufacturing methods, such as injection molding machines.

And considering that a real Monami 153 goes for 300 won, the cost isn’t that competitive, either.

However, the process of making the pen did give us a lot of food for thought.

“While we were making our own ballpoint pen, I found myself wondering about the manufacturing process, like why the body of the pen is hexagonal. I even came up with the tentative answer that it’s a structurally strong form that won‘t roll across a desk,” Shin said.

“Making the Monami ballpoint pen was kind of like the first stage of machine hacking,” Kang said. Machine hacking is the process of remaking an existing product by replicating the technology behind it.

Ironically, technological development has taken the individual further and further away from the technology. If artificial intelligence is introduced in the future, the alienation of labor is very likely to be taken to the extreme.

“In a situation where capital is monopolizing technology and young people are being alienated from information and resources, it occurred to me that 3D printers might have applications for young people, too,” said Shin, after making the ballpoint pen on the 3D printer.

A 3D printer is a weapon with which people can overcome the Machine Age. As humans strive to use 3D printers to move beyond the age of machines, perhaps we can be called “homo makers,” to show that we are the first humans to make something ourselves.

By Eum Sung-won, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 4Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 5Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 6Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 7Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 8[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 9[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 10‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be