hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Reportage] Investigating the boom in South Korea’s instant rice industry

Food columnist Baek Moon-young, 29, eats instant rice at least once a day. Part of it is the convenience, but the biggest reason is the flavor.

“Honestly, it’s better than the rice I make at home,” [she] said.

“The uniformity of the taste is one of its strengths. I can’t imagine life without instant rice,” she added.

As Baek’s story suggests, instant rice has become an integral part of South Koreans’ lives. Back when Haetban was launched as South Korea’s first instant rice brand in Dec. 1996, it was marketed as an emergency standby in case a family ran out of home-cooked rice; these days, it has become a regular part of the diet. The instant rice market has grown in scale from 27.8 billion won (US$24.4 million) in 2002 to over 400 billion won (US$350 million) as of 2017, with industry predictions putting it over the 500 billion won (US$438 million) mark this year.

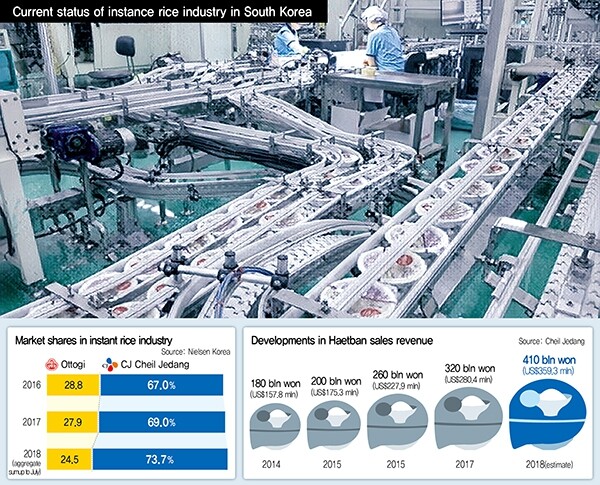

Original maker Haetban remains the dominant force in the instant rice market: the CJ Cheil Jedang brand’s market share stood at 73.7 percent as of July. In 2016, Nongshim ended its instant rice manufacturing efforts after 14 years; Dongwon F&B has just managed to keep hanging on. In practice, the market consists of just CJ Cheil Jedang and Ottogi.

Ottogi’s instant rice registered a market share of 24.5 percent in July, down somewhat from 28.8 percent in 2016. Haetban scored over 300 billion won (US$263 million) in sales and moved more than 300 million units last year; its 2018 sales are predicted to exceed 400 billion won. The Hankyoreh visited CJ Cheil Jedang’s factory in Busan’s Saha district on Oct. 18 to glimpse the secret behind its instant rice success.

The undisclosed secret behind a nine-month shelf life

Before entering the factory, I had to cover myself from top to bottom in cleanroom garments. Even after I had changed, stickers and absorbers were used to remove any remaining extraneous matter. A permanent manager was on staff to supervise the process. With requirements to wear headbands – and even mouth guards – most of the workers had short hair.

The first stop was the polishing area. This is where the brown rice – stored at low temperatures to prevent cracking – is transformed into white rice. Around the polishing stage, rice is passed several times through machinery to filter out extraneous matter. Once filtered, the rice has to pass through a color sorter – described as state-of-the-art equipment capable to detecting matter with other colors mixed in. The now whitened rice passes along the pipes into the production line area where it is to be cooked. The grains are rigorously sealed off to prevent exposure to the outside environment. Here, the rice goes through a process of cleaning and soaking. The cleaning equipment uses a similar motion to rubbing by human hands. Once cleaned, the rice is soaked in degassed water – oxygen having been removed to allow for even absorption by the grains. This step was necessary to ensure uniformity in flavor, I was told.

After the cleaning and soaking comes the cooking. Interestingly, the rice is not boiled and then transferred to a container; instead it is cooked in the container under high temperature and pressure conditions. Used since the product’s launch, this process was influenced by variables of hygiene, flavor, and efficiency.

There is one part of this stage that remains strictly confidential: the tuning of the pressure and temperature are key secrets. The process is optimized to reflect the grains’ condition, the weather, and other conditions, I was told. Pressure and temperature values are constantly being upgraded.

“Some of the researchers only eat side dishes for their meals because they spend all day eating rice to check the flavor,” said factory manager Lee Chang-yong, 48, who supervises the production process.

Another key Haetban secret concerns where the rice goes once it has been cooked. This is the part the company goes to the greatest lengths to conceal. Since it holds the key to its instant rice’s nine-month shelf life, the company was loath to give up the secret – even as it disputes accusations of preservative use. The clean room is where sterilized rice is sealed during cooking. I was the first reporter to set foot in the room, which is off-limits to visitors and photography. It is through conditions on par with a semiconductor plant that Haetban rice is able to last for nine months without the use of preservatives.

“Nothing goes into it besides purified water and rice,” insisted Lee Chang-yong.

Final check for flaws and irregularities

Another unique feature is the cooling process that comes after the packaging and steaming. Although it is intended to cool the rice down, it also allows checking for minute holes in the packaging. Even the slightest bit of water entering the holes would result in deviation from the standardized 210-gram weight. Those who think this is the last step have another thing coming.

Before the final packaging stage comes a process of radiation screening, optical screening, metal testing, and weight testing to filter out any extraneous matter that might have made it through. Just before the final packaging, the sealing is checked by eye, after which the containers are packed into boxes. The entire process is automated, with just 11 workers per production line to check for mechanical problems.

Flaws do occur. With 75,000 tons of Haetban rice produced each year, the defect rate stands at 0.3 percent – most of it errors in weight. Technology development efforts are under way to lower the defect rate.

Rise in single-person households puts instant rice in spotlight

In the distribution industry, Haetban’s growth is seen as the stuff of legend. When it was first launched in 1996 – a time when South Korea had no instant rice market – sales totaled just 4 billion won (US$3.5 million). With predicted sales above 400 billion won this year, the brand has experienced hundredfold growth in the span of 22 years.

The big secret behind the instant rice boom is the rise in single-person households. The percentage of single-person households in South Korea rose from 15.5 percent (2.26 million) in 2000 to 27.2 percent (5.18 million) in 2015. Statistics Korea predicts the number will pass 6 million (30 percent) by 2020 and reach 8.1 million (36.2 percent) by 2045.

Amid this rise in single-person households, Haetban’s annual sales passed 100 million units in 2011. As the home meal replacement (HMR) market began to expand, sales of instant rice took off, with Haetban moving 200 million units in 2015 and 330 million in 2017. Sales since 2011 account for 1.4 billion of the 2 billion units sold by Haetban since its launch.

The weather is another factor closely tied to instant rice sales. The number of households opting to buy instant rice rather than cooking their own appears to have risen amid the protracted hot spells this year. According to the mobile commerce company TMON, Heatban sales through Sept. 2018 were up by 106 percent from the same period in 2017 – more than double.

The company also named widespread adoption of microwave ovens and the employment of married women as factors closely tied to the growing instant rice market. The instant rice companies, for their part, are now targeting families rather than single-person households as consumers – one of the reasons for their emphasis on safety and flavor management.

An instant rice expert in his own right, factory manager Lee Chang-yong offered his own “choice tips.” His simple suggestions? Consumers wanting hard rice should remove the plastic cover entirely before putting the bowl in the microwave, while those who want softer rice can leave the cover on all the way.

By Lee Jung-gook, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 3[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 4After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 5[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 6Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 7US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 8All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 9[Photo] Smile ambassador, you’re on camera

- 10[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda