hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[News analysis] Breaking down the success of Starbucks in Korea

Whenever “S,” an office worker, got off at her subway stop, she would load up her Starbucks app and activate the mobile payment system called Siren Order. She wanted to get her drink as soon as she arrived at the coffee shop. She was craving a Cookies and Cream Frappuccino, even though the drink wasn’t technically on the Starbucks menu. So she put a Vanilla Cream Cappuccino in her shopping cart. Then she went into the “personal options” menu and selected “java chips” and “chocolate drizzle (a lot)” as her toppings. She also chose “fat-free milk” under the milk options. Voila — she’d created her own Cookies and Cream Frappuccino. She went into the Starbucks branch that was closest to the subway stop and picked up her drink. Just as she was about to head out the door, something came up that she had to deal with immediately. So she took a seat, fired up her laptop and plugged the power cord into an outlet. Signing onto Starbucks’ free Wi-Fi network, she was able to take care of business in no time.

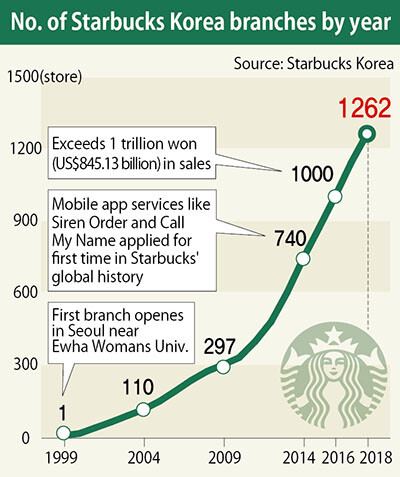

A customized approach to service, in which orders are prepared just the way customers want them; the Siren Order in-app feature, which lets customers place their order before they even get to the coffee shop; and the trend for people to take advantage of power outlets and free Wi-Fi to study or work at a café — these are just some of the changes that Starbucks has brought since its arrival in South Korea, 20 years ago as of next month.

Starbucks Korea has grown steadily over the past 20 years and is now ranked fifth in Starbucks’ global ranking, after the US, China, Canada, and Japan. Some of the strategies that have helped Starbucks succeed in Korea are its high-end image, its embrace of the café study crowd, and its localization.

From “equal parts coffee, sugar, and creamer” to Americano

Since it was established in Seattle in 1971, Starbucks has expanded into 78 countries around the world. The first Starbucks branch in South Korea opened near Ewha Womans

Starbucks is thought to have created a new coffee culture in Korea by providing an alternative to Korea’s traditional “dabang” (coffeehouse) culture. Coffee culture in Korea originated at dabangs in the 1960s and 1970s. Since there were few cultural spaces at the time, dabangs served as the center of popular culture. They even hosted book launch events and poetry readings. The formula for coffee at a dabang was coffee, sugar, and creamer, in equal parts. Starting in the 1980s, coffee gained widespread popularity. Thanks to the development of coffee vending machines and instant coffee, it was now possible to drink affordable coffee whenever and wherever you wanted to. In the 1990s, there was a brief trend of coffee shops selling hazelnut coffee.

The appearance of Starbucks served as a turning point in Korea’s coffee culture. Dabang-style coffee gave way to Americanos and café latte, while people began getting coffee to go, carrying it in disposable cups and drinking it as they walked along the street. That unleashed a flood of coffee chains, including Coffee Bean and Tea Leaf, Ediya Coffee, Tom N Toms, and Twosome Place.

Starbucks didn’t win Koreans over all at once. An Americano brought a frown to the face of those accustomed to coffee served at dabangs, sold in vending machines, or prepared from an instant mix. At a time when people took it for granted that an employee would serve their coffee, it wasn’t easy to adjust to “self-service,” the idea that customers had to pick up their drink themselves. Others were repelled by unfamiliar names on the menu, like “caramel macchiato,” and by the shock of a cup of coffee costing upwards of 3,000 won (US$2.53).

Haters had a field day with Starbucks, lampooning the company for selling coffee that cost as much as a meal and alleging that only ostentatious, image-conscious women went there. But the number of customers who preferred Starbucks’ unique vibe and its friendly employees gradually began to increase. Paradoxically, the mockery about ostentatious women only served to reinforce the brand’s high-end image. In 2016, Starbucks created “reserve branches,” where the drinks cost 2,000 or 3,000 won (US$1.69-2.53) more than ordinary ones. Currently, the number of reserve branches has risen to 50, confirming that Starbuck’s high-end strategy is working.

Absorbing the café study crowd instead of insisting on quick turnover

Another strategy that Starbucks adopted was accepting customers who linger for a long time. Since coffee shops and restaurants need to have quick customer turnover if they want to increase sales, they typically frown on customers staying for hours at a time. But Starbucks created an environment conducive to customers who want to stick around. It was the first coffee chain in the country to provide free Wi-Fi service in its branches, and it also installed power outlets at every branch to make it convenient for anyone to study or work. By welcoming customers who enjoy studying at cafés, Starbucks gained a competitive edge in the café market. Coffee Bean and Tea Leaf, an early rival, lost ground after it chose the opposite course as Starbucks and refused to install Wi-Fi or power outlets. As word spread that Starbucks was a good place to work or study, it picked up more loyal customers who did everything at Starbucks.

“At Starbucks, no one gives you a bad look if you stay there too long, and the high speed of the Wi-Fi is good for working. The music they play also seems to be selected to aid concentration,” said Lee Na-hyeon, a 29-year-old office worker.

In recent years, however, some have observed that more and more Starbucks branches are decreasing their number of power outlets or eliminating them altogether. In fact, there are no outlets at Starbucks branches at the main Shinsegae Department Store in Seoul, at Incheon Airport, or at Starfield Hanam, a shopping complex in Gyeonggi Province.

“All we’ve done is make some changes at branches with a large transient population or with a lot of customers who want to take a quick break from shopping — at department stores, for example. Customers at such branches tend to prefer comfortable seats, such as sofas, and few of them are looking for power outlets,” said a spokesperson for Starbucks. “On the other hand, we’ve installed power outlets and USB ports at our one-person seats.”

Starbucks has also reaped dividends from its localization strategy of swiftly adopting services that are suited for Koreans’ preferences and propensities. Siren Order can be seen as mirroring Koreans’ “ppali ppali,” or “fast fast,” culture — the tendency to want things done right away. Starbucks Korea developed Siren Order independently in 2014, before Starbucks in other countries. The service was designed to keep customers annoyed with long lines at busy times from defecting to other coffee branches. Customers load up to the app to select their item and branch and then pay for their order. Next, Starbucks uses location-based high frequency beacons to alert the branch when the customer is approaching so that the customer can pick up their drink as soon as they arrive. In the summer of 2015, Starbucks’ headquarters launched Mobile Order and Pay in their US branches, modeling the service after Korea’s Siren Order.

Starbucks has also developed menu items that cater to the Korean palate. Since 2007, it has employed local Korean products in a wide range of drinks, including the Mungyeong Omija (Magnolia Berry) Fizzio, Gwangyang Yellow Plum Fizzio, Gongju Chestnut Latte, and Icheon New Rice Latte. Each year, Starbucks launches an average of 35 new drinks, 90% of which are produced independently in Korea.

“Headquarters in Seattle also develops drinks for distribution around the world, but those tend to be too sweet for Koreans. We do implement some of those drinks after adjusting their recipes, and our in-house beverage development team also creates new menu items,” said a Starbucks spokesperson.

[%%IMAGE3%%]

A coveted tenant for building owners

Every year, Starbucks adds at least 100 new branches. While common sense would suggest that value would go down as quantity goes up, Starbucks has instead become one of building owners’ favorite brands over the past few years. Since all Starbucks branches are operated directly by the company, they make long-term contracts, generally for at least five years, which gives building owners little reason to worry about the café vanishing and leaving a vacancy. On top of that, Starbucks branches bring in a large number of customers, which has the effect of giving the building a youthful and energetic atmosphere. There’s even talk about a “Starbucks impact area,” rather like the “subway impact effect” that describes the brisk business enjoyed by establishments located close to a subway station. When a Starbucks moves into a building, it’s thought to increase sales in the stores nearby and to even raise the market price of the building itself.

There are reportedly quite a few building owners who have taken the initiative to contact Starbucks about opening up a branch in their building, with the hope of taking advantage of the “Starbucks impact area.” But since all Starbucks branches are directly run, the decision to open a new branch is made in line with standards created by the in-house branch development team.

After finding areas with sufficient demand and setting priorities, the branch development team looks into new buildings and properties for sale to narrow down the potential spots for a new branch. The team has also drawn up a map that charts Starbucks’ national development plan, plotting every potential site for a new branch in the country. The map marks all the subway stations around the country and areas where new stations are supposed to be built, calculating the number of potential branches according to the size of each station. There are four potential branches allotted for each subway station in Seoul and two for each station in Busan. The team has used the same methods to look into the number of bus stops, while taking into account the volume of passengers who embark or disembark at each stop.

“The areas we’re focusing on are subway stations, where there’s a large floating population, and commercial zones downtown with a lot of office workers. Next, we look at concert halls, movie theaters, sports facilities, KTX stations, and airports — basically, buildings where a lot of people get together,” a Starbucks spokesperson said.

One of the reasons Starbucks has been able to expand its number of branches so quickly is regulations. Unlike franchise café chains, Starbucks isn’t subject to regulations about opening branches because all its branches are directly operated from headquarters. According to the Franchise Business Act, franchise chains such as Ediya and Twosome Place are required to keep a certain distance from existing franchise outlets so as not to jeopardize their business. That has prompted the small business community to call out Starbucks for cleverly exploiting a loophole in the regulatory scheme.

Yu Seung-ho, a professor of video and culture studies at Kangwon University, is the author of “Starbucksization,” a book that analyzes the phenomenon of Starbucks’ success in Korea. “Starbucks has been benefiting from a recent trend in Korean for people to seek a comfortable lifestyle amid our complicated world. It fits with the psychological desire for protection and respect, along with gaining recognition from other people,” Yu said.

“Korea isn’t like Italy, where cafés are an integral part of everyday life and culture and where there’s low-level competition between baristas who each have their own technique for brewing coffee. That has paved the way for the success of Starbucks, where customers can count on a certain standard of taste and quality [even if that’s not outstanding] whichever branch they visit.”

By Shin Ji-min, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 2Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 3Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 4Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 5‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 6[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 7N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 8[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 9[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 10Kim Jong-un expressed ‘satisfaction’ with nuclear counterstrike drill directed at South