hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Only 2 out of 10 top S. Korean companies have a female executive

1, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0.

These are the numbers of female board of director members at South Korea’s 10 largest companies by market capitalization. Even among those numbers, the first “1” (at Samsung Electronics) was in response to a shareholder suggestion, with the US-based hedge fund Elliott commenting in 2016 that the Samsung Electronics board was lacking in gender diversity in comparison with competitors like Apple. With the figures embarrassing even relative to the “global standard” of 20.6% representation for female board members, a bill recommending the inclusion of at least one female member when large corporations with assets of 2 trillion won (US$1.69 billion) or more are establishing their board composition is currently awaiting passage in the National Assembly’s regular session.

While the discussions in related standing committees have backpedaled considerably from an earlier draft requiring a minimum female board representation of one-third, many are watching to see when changes the law will mean for South Korea’s uniformly male corporate boards if it does pass.

According to accounts on Dec. 2 from the National Assembly, the Legislation and Judiciary Committee voted on Nov. 27 to approve a partial amendment to the Financial Investment Services and Capital Markets Act, which would create a new provision requiring “efforts to ensure that not all members of boards of directors for listed companies with at least 2 trillion won in assets belong to a particular sex,” as well as “elective reporting of compliance.” While the bill was expected to pass the National Assembly’s regular session on Nov. 29, its schedule now appears unclear following a filibuster request by the Liberty Korea Party (LKP).

The bill, which was presented in October 2018 by chief author Choi Woon-youl of the Democratic Party, has undergone major changes through the presiding National Policy Committee and Legislation and Judiciary Committee due to concerns about the burden it would place on businesses. A provision in the amendment’s draft version stated that “directors of one particular sex should not exceed two-thirds of the total board membership” -- effectively requiring that at least one-third of board members must be women. A requirement was also included for companies to specify the grounds for failure to comply in their business reports.

During a review last month by the National Policy Committee’s legislation subcommittee, members expressed strong support for the bill’s aims, including its attempt to address the glass ceiling for women.

“There are issues with companies and our societal structure failing to groom such [female] individuals, but it seems like it’s too late to do anything about that now,” said Sung Il-jong, an LKP lawmaker. “I think it would be a good idea to introduce this quickly as subject to obligatory reporting.”

But most members raised issues with the one-third requirement being “excessive” and the obligatory reporting terms placing “a major burden on companies.” Kim Jin-tae, an LKP lawmaker, said, “If [a company] says it failed to meet its quota, there will be an uproar with civic groups talking about things like the ‘10 worst companies for misogyny.’”

“I can’t support forcing businesspeople in one direction,” he added.

The obligatory reporting was also opposed by the Financial Services Commission (FSC), which would be the presiding agency for the law. In response, the National Policy Committee agreed on a plan that would reduce the minimum number of female board members to one and institute elective reporting of compliance by companies.

At the Legislation and Judiciary Committee meeting on Nov. 27, even the minimum representation “requirement” was replaced with “efforts.” The opinion was that with regulations mandating “efforts” to achieve a balance of sexes in place with different state and local government organizations, the question of whether to include enforcement regulations in the price sector required consideration in terms of business freedom and private autonomy. While views characterizing the requirements as “reverse discrimination against men” and excessive regulation of business activities gained support, Back Hye-ryun, a lawmaker with the Democratic Party, commented that the “[legislation] investigation have a mistaken understanding of things” and shared some overseas examples.

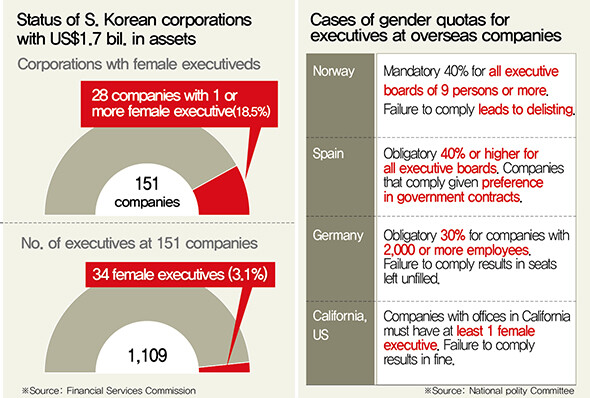

What other countries have done to implement corporate gender equalityNorway, which became the first country to institute a quota for female executives in 2003, stipulates a distribution of at least 40% male and 40% female members in the cases of boards with nine or more members. Failure to comply results in mandatory organizational changes and may ultimately lead to delisting. In Germany, the roughly 110 listed companies with at least 2,000 employees are required to have oversight boards (the equivalent of outside directors) consisting of at least 30% women; in the event that the ratio cannot be met, the seat in question is to be left vacant.

Small and medium-sized businesses must announce independent ratios as business targets. California required that listed companies with a main office in the state according to company law must have at least one female member on their board by the end of this year. By 2021, at least three female board members will be required in cases of boards with six or more members, with noncompliance potentially resulting in fines being imposed.

As of late 2018, the FSC counted 151 listed companies in South Korea with at least 2 trillion won in assets. Of their collective total of 1,109 board members, women represented just 34, or 3.1%. According to an analysis of 3,000 companies around the world published by Credit Suisse in October, South Korea’s 3.1% percentage of female board members ranked it dead last among 40 countries examined, behind Japan (5.7%) and Pakistan (5.5%). The percentage fell far short of the 20.6% average for all countries, let alone the ratios of 44.4% for top-ranked France and 40.9% for second-ranked Norway.

“The overall conclusion of research has been that establishing board diversion in terms of things like gender distribution is helpful in escaping the tendency toward ‘groupthink’ and in managing crises and achieving results,” said Park Kyung-suh, a business professor at Korea University. For this reason, many global institutional investors regard board diversity as a key factor when weighing investment decisions. In other words, the matter was already one requiring active steps in corporate risk management terms ahead of any legal regulations.

Some observers contend that the Capital Market Act amendment “lacks substance,” with its provisions calling for “efforts” and lack of prescriptions for punishments. But Lee Bok-sil, a former Minister of Gender Equality and Family who currently chairs the association Women Corporate Directors, said that the relevant groups would “monitor board appointments by companies with at least 2 trillion won in assets and announce what they find.”

“The companies are going to find themselves facing social pressure,” she said.

In a telephone interview the same day with the Hankyoreh, Choi Woon-youl said, “There are some disappointing aspects, but it’s important to take that first step.”

“I’m looking forward to this bringing qualitative changes to corporate boards,” he said.

By Park Su-ji, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 4Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 5US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 6[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 7All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 8[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda

- 9Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 10More South Koreans, particularly the young, are leaving their religions