hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[News analysis] The evolution of S. Korean convenience stores over the 38-year history

“Since convenience stores have the most accessible distribution network and also serve a partially public function, leaving them off the list [of public mask retailers] doesn’t serve the goal of providing consumers with a stable supply of masks,” the National Association of Convenience Store Franchise Owners said in a statement on Feb. 26. The association was responding to the government’s designation the previous day of Nonghyup Hanaro supermarkets, post offices, and pharmacies as the only places for selling public supplies of masks.

South Korea isn’t the only country where convenience stores have been seen as serving a public function at a time of crisis. When the Tohoku earthquake struck Japan in 2011, convenience stores were nicknamed “lifelines”: thanks to their highly extensive distribution networks permeating the nation like capillaries in the body, convenience stories were used to supply relief goods to affected areas. Despite disagreement in South Korea about whether convenience stories should be an outlet for the public distribution of masks, it’s undeniable that the role of the “tiny but mighty” convenience store is getting fresh attention amid the spread of COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus. This article examines how far convenience stores — which were once regarded as little more than a dressed-up corner store — have come during their 38-year history in the country.

Convenience stores once classified as “corner stores”

The earliest convenience stores in South Korea appeared in 1982, when the chain “Lotte Seven” opened up its first branch in front of Yaksu Market in downtown Seoul. According to an article in the Maeil Business Newspaper titled “Korea sees first convenience store, a new type of corner store,” this outlet was open from 7 am to 11 pm, 365 days a year. The main items were food, but it also carried miscellaneous items and household goods, the article said. The store’s area measured about 132 square meters, nearly twice the average size of today’s convenience stores (73 square meters).

But the Lotte Seven chain soon had to close because its prices weren’t competitive enough, and South Korea’s convenience store saga didn’t resume until 1989. That was when a 7-Eleven opened for business at the Olympic Village in Seoul’s Songpa District, the first outlet in Korea to be open 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, under the convenience store’s basic business model. Newspaper articles at the time speculated that these all-night stores were targeting singles and dual-income couples.

It was around this time that both foreign and local convenience store chains took the stage. The dominant convenience store chains in the 1990s were Japan-based Lawson, Family Mart, and Ministop; US-based ampm and Circle K; and homegrown LG25 and By the Way. Backed by huge investments, these chains strove to make convenience stores ubiquitous, opening branches far from the bustling greater Seoul area. Just four years after the convenience store revival, there were 1,000 outlets around the country, demonstrating that they’d established themselves in the country’s distribution network.

Soaring numbers of convenience stores: one for every 1,248 people

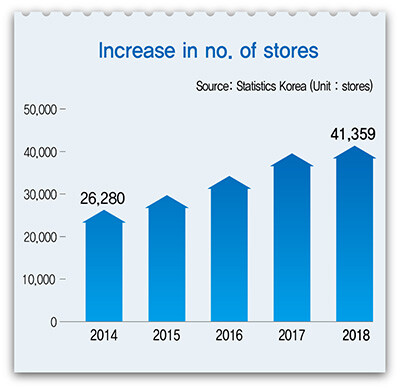

Over nearly 40 years since their first appearance in South Korea, convenience stores have surged in number and been transformed along the way. This growth is evident in the statistics: in the five years between 2014 and 2018, according to franchise data maintained by Statistics Korea, the number of convenience stores rose at an annual rate of between 3,000 and 5,000. The number of convenience stores hit 41,359 in 2018, the first year they’d topped 40,000. That’s one convenience store for every 1,248 people in the country — an even higher concentration than in Japan (one per every 2,249 residents), a country famous for its convenience stores. The Korean market is worth 21 trillion won (US$17.58 billion).

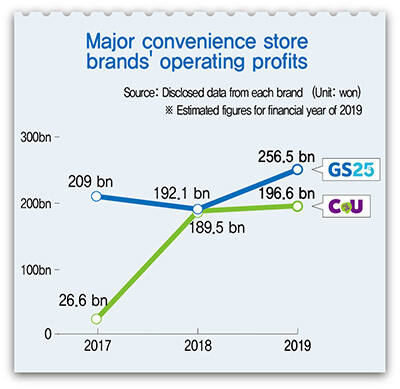

All that growth has brought corresponding changes. As the market expanded and competition grew fierce, convenience stores have begun extending their services into entirely different industries. The most widely adopted extension is banking. After installing ATMs in the early 2000s, convenience stores began functioning as a kind of “mini bank.” At branches that have partnered with banks, customers can get a new check card, change their account password, and pay their bills; the ATMs at some convenience stores even give loans. According to GS25, a convenience store chain with ATMs at some 18,000 outlets, 65.8 million deposits, withdrawals, and remissions were conducted at its outlets in transactions exceeding 11 trillion won (US$9.2 billion). “Every day, 30 billion won [US$25.1 million] worth of transactions are being made at GS25s,” the chain said.

Convenience stores have recently been turning their attention to delivery, a lifestyle service that had previously been limited to hypermarkets. Through partnerships that convenience store chains have forged with delivery apps, customers are able to order essential goods with mobile apps and have them delivered from a nearby outlet for a fee of 3,000 won (US$2.51). The chain CU was the first to introduce a delivery service at a small number of outlets in 2010, with staff taking orders over the phone and delivering the goods themselves. “Over the past few years, revenue from our delivery services has been increasing by an average rate of 25% each quarter,” the company said.

Other services that the convenience store industry has tried out include mediating bill payments, developing photos, selling baseball tickets, selling insurance, collecting mobile phones, collecting dry-cleaning, selling airplane tickets and vehicle sharing. “Since a number of convenience stores are in close proximity to consumers’ range of activity, they’re forced into fierce competition over lifestyle services to provide customers with more convenience,” said one industry insider.

As growth slows, convenience stores strive to develop “killer content”The competition over various services at convenience stores is likely to continue in the future. In 2020 projections for the retail and distribution industry published last year, Korea Investors Service, a credit assessment agency, predicted that convenience stores would maintain decent growth but said the industry needs to develop “killer content,” since its growth curve is gradually leveling off.

“Despite a rising preference for convenience and consumption nearby, the convenience store industry has been so aggressive at opening new outlets that there’s little chance of a major increase in the number of outlets. If convenience stores can’t develop another ‘killer’ item like prepackaged meals, there’s unlikely to be a major increase in the number of items bought or their price,” the report said.

“When there were fewer than 10,000 outlets [in the country], the industry was focused on ‘accessibility’; but now that there are more than 40,000 outlets, chains have to make themselves stand out through ‘content’. We have to induce customers to walk the extra 300m to a specific brand of convenience store in order to purchase services and products that other brands don’t have,” an industry insider said.

By Shin Min-jung, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/8317138574257878.jpg) [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father![[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms? [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/3617138579390322.jpg) [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 2Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 3[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 4Opposition calls Yoon’s chief of staff appointment a ‘slap in the face’

- 5Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan

- 6Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76

- 7[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 8[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 9New AI-based translation tools make their way into everyday life in Korea

- 10Survey: S. Koreans spend more time using smartphones than eating