hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] Japan’s “flashy but cool” golden age has ended

In the 1980s, Korean elementary school kids used to go around singing “Gin gira gin ni.”

I was living in Masan, in South Gyeongsang Province, at the time. Rather like Busan, Masan was a port city that saw a rapid influx of Japanese culture while it was growing during the colonial period.

A number of karaoke rooms popped up in the city around that time, though not legally. Until the Kim Dae-jung administration opened up South Korea to Japanese culture in 1998, all Japanese culture and products were illegal.

People tend to crave what they’re not allowed to have. Many elementary school kids in the 1980s carried around what we called “elephant thermoses,” which were brought into Korea by under-the-radar importers. The thermoses were manufactured by Zojirushi, which means “elephant brand” in Japanese.

I carried around an elephant thermos myself. When I unpacked my lunch and popped open the top of the thermos, everyone would be amazed to see the steam rising from my soup. The thermos was indubitably an artifact from an advanced country.

South Korea was akin to a backwater village, with no hope of catching up to Japan. In the 1980s, Korea’s gross domestic product was just one-seventeenth of Japan’s.

Koreans’ per capita income was US$1,686, while Japan was closer to US$10,000. Japan was an advanced country; Korea, a developing country that had just begun to rise from poverty.

Obviously, that led to cultural differences as well. The Japanese culture that was smuggled into the country looked unbelievably advanced, even through the eyes of an elementary school student.

My father, who was the captain of a merchant ship, would sometimes bring Japanese magazines back home with him. I used to stubbornly read through the magazines, even though I didn’t know Japanese. With their glossy pages and bold colors, they were so different from the magazines printed in Korea. I envied Japan so much it hurt.

That brings us to “Gin gira gin ni,” the lyrics I mentioned above.

I can’t remember where on earth the trend got started. At some point, kids started singing a Japanese song, but the only part they got right was “Gin gira gin ni.”

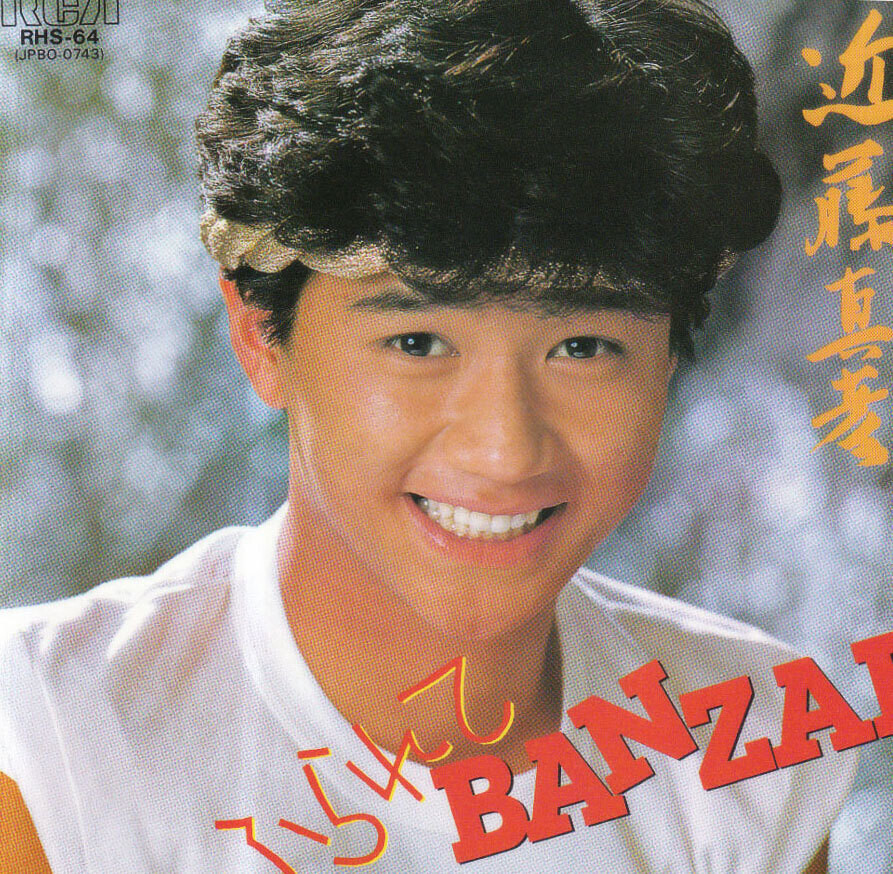

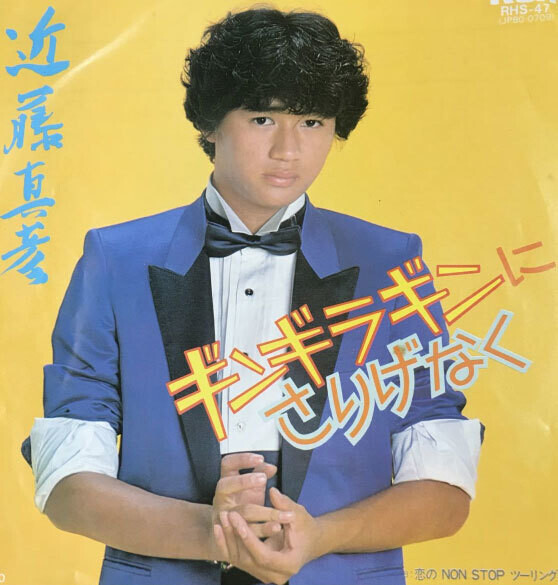

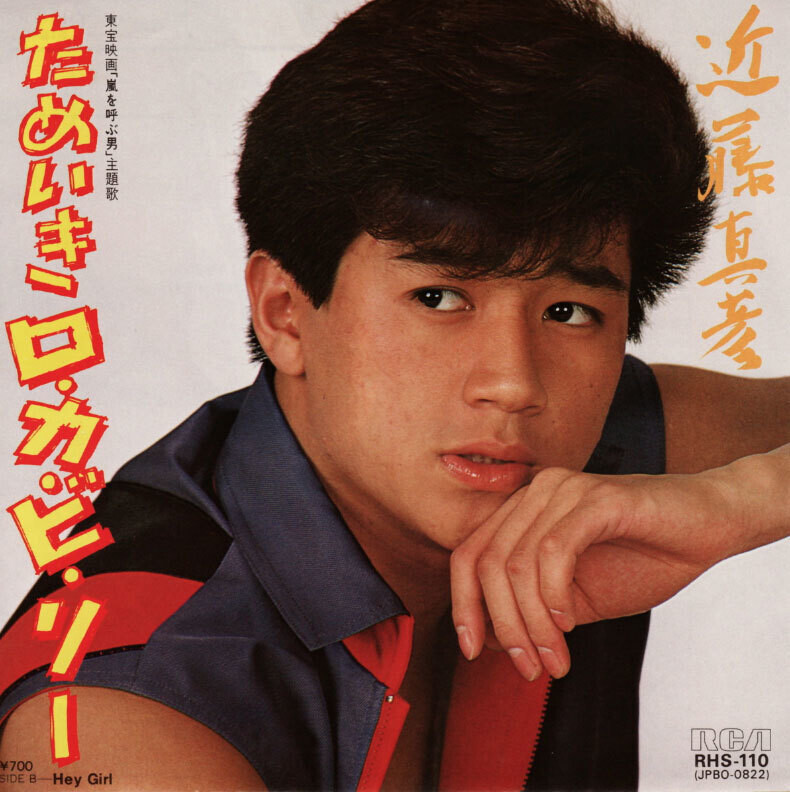

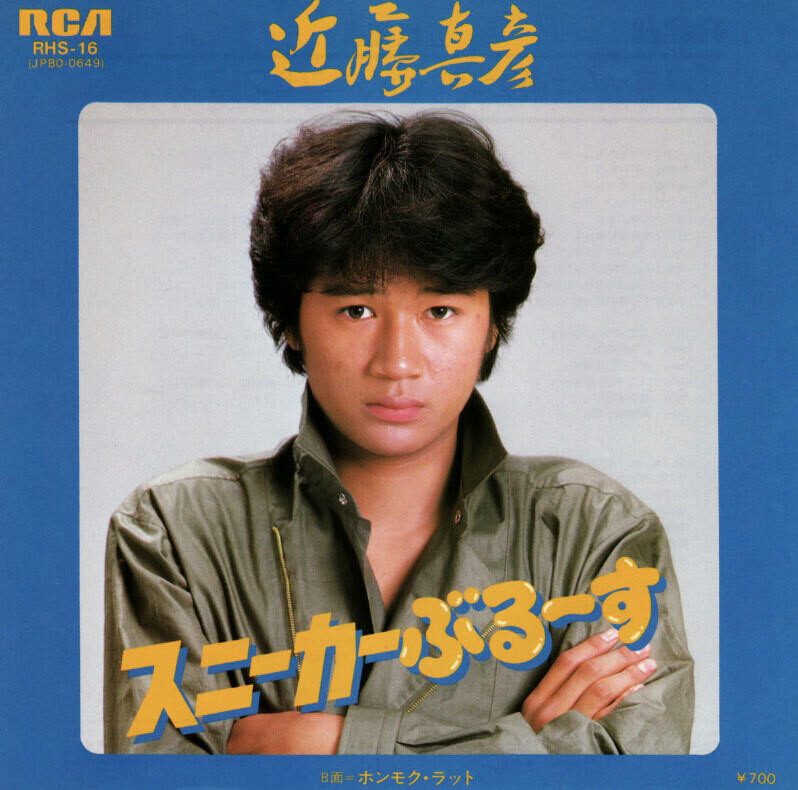

I soon found out that the lyrics were from the song “Gin Gira Gin Ni Sarigenaku,” released by Japanese singer Masahiko Kondo in 1981. The title could be roughly translated as “flashy but cool.”

This funky dance track on our illegal cassette tapes was pretty catchy, and we never got tired of humming it. There were basically no dance tracks in Korean popular music at the time.

It wasn’t until Nami’s “Binggeul Binggeul” (meaning “round and round”) came out in 1984 that I realized that Korea had any music like that. So, you can imagine how much of a cultural shock “Gin Gira Gin Ni Sarigenaku” must have been for a Korean elementary school kid in the 1980s.

Masahiko Kondo was a pop idol who also symbolized the Japanese economic bubble of the 1980s. Soon after Kondo debuted in 1979 with Johnny & Associates — the Japanese talent agency that served as a model for Korean agencies — his hit “Gin Gira Gin Ni Sarigenaku” made him a national sensation. Japanese men imitated Kondo’s hairstyle; he was the person who popularized Nike sneakers in Japan.

Johnny & Associates was founded in 1962, but the modern pop idol industry didn’t begin until the 1980s. And that beginning owes a lot to Kondo.

There weren’t any pop idols in Korea back then. Hye Eun-yi could be regarded as Korea’s first idol, but her songs still belonged to the adult contemporary genre.

Kondo’s popularity kept growing throughout the 1980s. In 1987, he won the “grand prix” at the Japan Record Awards. But his glory days didn’t last for long, as is always the case with manufactured pop idols.

Once the 1990s arrived, new pop idols entered the pantheon. By the time Takuya Kimura (a member of the group SMAP, which was also well-known in Korea) reached the peak of his popularity in the 1990s, Kondo had become a little dated.

“Flashy but cool, that’s how I roll. / Flashy but cool, just playing it cool in my life,” Kondo had sung in his breakout song in an occasionally creaky voice that dripped with confidence.

But those days were almost over. The curtain was falling when the Japanese could sell a home in Tokyo and live in the US on the proceeds.

The bubble burst in the 1990s with a tremendous bang. That was when Japan’s lost decade began.

When I started university in 1994, I would download Japanese TV shows and watch them over and over again. That may be illegal now but bear in mind that this was a time when music website Napster “legally” made every song in the world available for free.

“Long Vacation” (1996) and “Love Generation” (1997) — both starring Takuya Kimura, Japan’s hottest superstar at the time — were a bible of sorts for university students who were closet fans of Japanese culture.

While Korea had started to produce trendy dramas, they still felt pretty trite compared to those being made in Japan.

Both of those dramas were recently posted on the Watcha Play streaming service; they’re worth a watch. They preserve the glittering vision of Tokyo as the world’s trendiest city right before the bubble burst, rather like a fossil of a dinosaur that failed to foresee the asteroid impact.

I’m writing this article while watching a late-night news show. News about the Olympics shows the decay of what I used to regard as the richest, most elegant, and most orderly country in the world.

To be sure, Japan is in the grip of the uncontrollable COVID-19 pandemic. But it seems that Tokyo was totally unprepared for this massive international event.

The Japanese are probably in panic mode. If things had gone as planned, the Olympics were supposed to symbolize the country’s recovery. They ought to have been one big ego boost for the Japanese. But Koreans are the ones getting an ego boost.

Watching Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga’s wishy-washy response to South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s proposed visit to Japan suggested a certain discomfort and dismay. It’s fair to see that as the inability of the Japanese to accept that the rednecks next door, the people who once tried so hard to imitate them, are now becoming their equals.

I read the book “The Era of Overtaking,” which one of my former co-workers co-authored. As soon as I heard the title, I started slapping my knee until it stung.

I’m not sure who came up with the word “overtaking,” but I have to admit that it really is perfectly apt. South Korea truly has entered an “era of overtaking.”

The UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) upgraded South Korea’s status from a “developing” to a “developed” economy. It’s the first time since the organization was founded in 1964 that any of its members has been promoted to developed economy status. I also read in the news that South Korea had surpassed Japan in terms of per capita purchasing power.

As a South Korean in my forties, I always saw Japan as something to be overcome. To those in their teens and twenties, Japan is another country with a similar living standard to South Korea’s — just with more compulsively clean streets.

No one who watches Japanese TV finds themselves longing to live in Tokyo. South Koreans of middle age and older may still have a bit of an inferiority complex when it comes to Japan, but the new generations don’t. They’re already living in the era of overtaking.

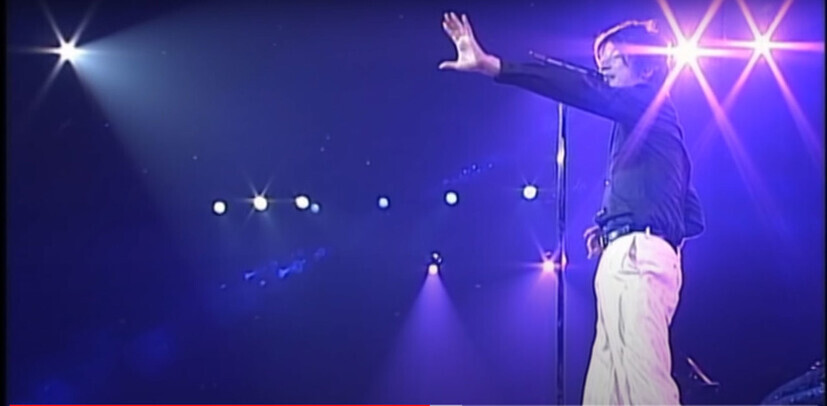

These days, I often re-watch a YouTube video of Masahiko Kondo performing “Gin Gira Gin ni Sarigenaku.” I see a young man fresh out of his acne stage, singing passionately as he bops with dancers on a gaudy stage. Today, it all looks like a bygone symbol of a golden age — “with a flash, but playing it cool.”

Then I flip over to a music video by BTS. They’re a new symbol of a golden age that’s just getting started.

It may be that we’ve finally reached a point in time where South Korea and Japan can look at each other as equal partners and show what’s really on our minds.

The age of callow 20th century “Japan envy” is over. We’re entering a new era of 21st-century friends.

By Kim Do-hoon, former editor of the Huffington Post Korea

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 4[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 5Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 6All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 7US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 8Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 9[Photo] Smile ambassador, you’re on camera

- 10[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes