hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

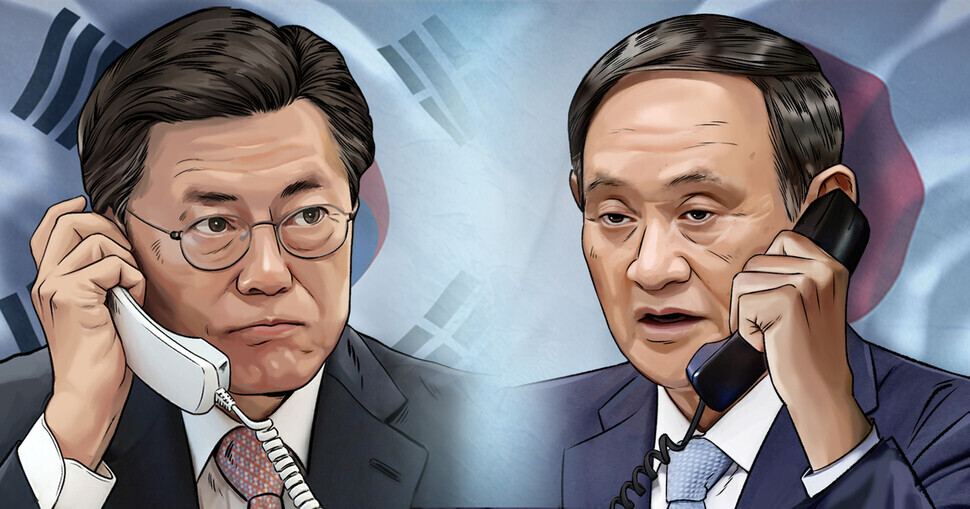

[Column] Dynamic between S. Korea, Japan has fundamentally changed

South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s proposed visit to Japan during the Tokyo Olympics and his summit with the Japanese prime minister have fallen through, placing the two countries’ relationship in even more of a bind.

There are several reasons the Tokyo Olympics couldn’t serve as an opportunity for diplomacy, but the fundamental one is a shift in the nature of Korea and Japan’s relationship. Ever since the two countries normalized diplomatic relations, their relationship has been grounded in Korea’s moral superiority as the victim of colonization and Japan’s shame as the more powerful aggressor state.

The nadir in the South Korea-Japan relationship, at least from Korea’s point of view, was the abduction of Kim Dae-jung in 1973. The Korean Central Intelligence Agency seized Kim, the opposition party’s presidential candidate, while he was visiting Japan.

Kim’s kidnapping was a serious breach of Japan’s sovereignty — so serious, in fact, that it prompted Japan’s opposition party, along with other issues, to bring a vote of no confidence. The affair placed Korea in an awkward position vis-à-vis its relationship with Japan.

But there was a complete reversal of the situation one year later, when Mun Se-gwang, a Japanese of Korean descent, attempted to assassinate then-South Korean President Park Chung-hee during an event on Aug. 15, a holiday celebrating Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule. Mun didn’t hit Park, but a stray bullet did hit first lady Yuk Young-soo, who later succumbed to her wound.

The Park administration pressed Japan to take responsibility for the incident. Japan eventually sent a delegation to convey an apology, distracting attention from the abduction of Kim Dae-jung.

The reason that a deliberate violation of Japanese sovereignty by a South Korean intelligence agency could be overshadowed by a mistake by Japanese law enforcement was the tendency to regard Korea as the victim and Japan as the aggressor.

Mainstream postwar politicians in Japan who were knowledgeable about Korea tended to hold simultaneous feelings of superiority and shame toward their neighbors. Their attitude was that Japan, the “stronger” big brother, should take pains to appease Korea, the “weaker” little brother. That attitude led those politicians to make offensive remarks about past disputes between the two countries, but also to apologize for those remarks.

This relational dynamic saw its heyday in the Japan–South Korea Joint Declaration signed by South Korean President Kim Dae-jung and Japanese Prime Minister Keizo Obuchi in 1998, in which Obuchi “expressed his deep remorse and heartfelt apology” for Japan’s colonial rule of Korea.

As Japanese born after the war became the mainstream of the Japanese political establishment and as the disparity between South Korea and Japan narrowed, the view of Japan as older brother and Korea as younger brother began to fade.

Japan’s postwar politicians have retained their sense of superiority over South Korea, but they’ve lost their sense of shame. The upshot is that old diplomatic patterns no longer work when employed by Koreans, who still harbor anti-Japanese sentiment.

Korea dialed down its expectations for holding a summit with Japan during the Olympics. It wanted Japan to retract the export controls put into place last year in exchange for Korea reinstating its GSOMIA information-sharing agreement with Japan. Even so, Japan rejected the offer.

The Japanese press described this as Korean “brinkmanship” — simply because Korea insisted that the summit with Japan should have results.

The very fact that Korea offered to normalize GSOMIA, which is something that Japan wants, if Japan rolled back the export controls, which would have few benefits for Korea, suggests that the relational dynamic between Korea and Japan has shifted since the time of the Kim Dae-jung kidnapping and the attempted assassination of Park Chung-hee.

There’s something suggestive about the recent remarks made by Hirohisa Soma, deputy chief of mission at the Japanese Embassy. He controversially used a sexual expression while saying that “the Japanese government doesn’t have as much time to worry about bilateral relations as Korea assumes.”

Soma’s remarks could mean that South Korea needs Japan more than vice versa, but they could also mean that Japan can’t afford to be as generous as it used to be.

When asked about the failed attempt to set up a summit with Moon, Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga said that Japan “will continue clear communication with the South Koreans based on our consistent position.”

What Suga means is that he won’t hold a summit unless Korea comes up with a solution to the “comfort women” and forced labor issues that is satisfactory to Japan.

In the past, Japan has solved problems in its relationship with Korea, but now Korea is saddled with that task. That spells the end of Korea-Japan relations as we know them.

By Jung E-gil, senior staff writer

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0422/1717137715201877.jpg) [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far![[Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0422/1517137717613239.jpg) [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

[Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

Most viewed articles

- 1Korean government’s compromise plan for medical reform swiftly rejected by doctors

- 2[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 3[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 4[Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- 5Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 6[Reporter’s notebook] Did playing favorites with US, Japan fail to earn Yoon a G7 summit invite?

- 7All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 8[Interview] “We are in a revolutionary moment”: Art is expanding in the AI era, says scholar

- 9[Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- 10Korea protests Japanese PM’s offering at war-linked Yasukuni Shrine