hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] Jogakbo, the patchwork herstory of Korea

By Chung Byung-ho, Professor Emeritus of anthropology at Hanyang University

The patchwork quilts made by black slave women are still vivid in my memory. I saw them at the National Quilt Museum in Paducah, Kentucky, years ago. My heart trembled as I looked at the ragged quilts made with scraps of cloths. The women, who were treated like animals, had pursued beauty with simple materials. They made me realize how strong the human spirit is that it did not break despite the oppressive reality. Some of them expressed the spirit of fierce resistance by showing the harsh reality of slaves in embroidery, or by patterning the secret Underground Railroad codes that guided the way to freedom.

In front of the museum, a profluent river flowed. It was the Ohio River, where Eliza, a runaway slave woman carrying a baby, jumped across drifting ice as though they were steppingstones. It was wider and faster than I had imagined as a child when reading “Uncle Tom's Cabin.”

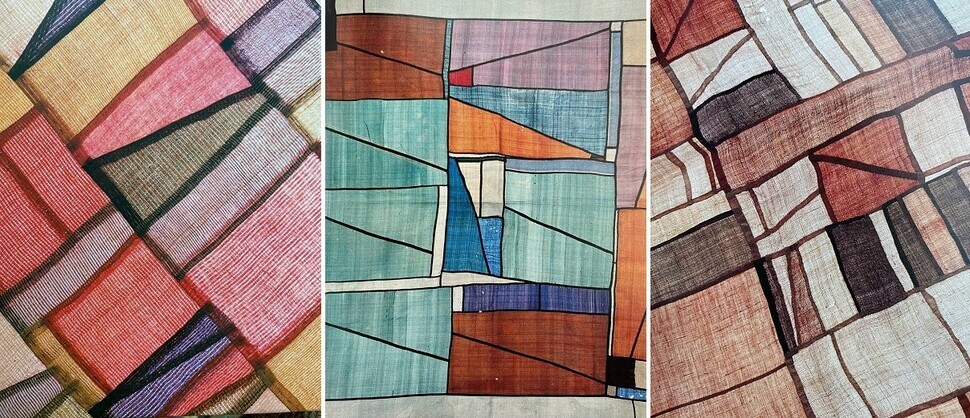

Jogakbo, the Korean traditional patchwork, is drawing worldwide attention as a creative folk craft these days. Several decades ago, it was considered only a relic of the poor past. I didn't particularly like jogakbo; it reminded me of the sewer’s patience as she labored under the oppression of patriarchy regardless of her status or age, whether she was a gentry girl or a poor old maid.

These days, I have come to appreciate the artistic combination of lines and facets in jogakbo. The creativity in stitching fabrics of different sizes and colors is amazing. Perhaps I am just beginning to admire the aesthetics of a free soul that discrimination and oppression could not suffocate.

A feminist peace movement group called Jogakbo has been holding meetings they call “Life Stories of Korean Diaspora Women” continuously for the past decade. It created a place where Korean women who have been forced to live in divided North and South Korea and various neighboring countries in modern history could share their life experiences. They participated in “equal dialogue” where they listened to others’ life stories with equal respect, regardless of their background. They spoke out with no reservation.

When a woman from North Korea said, “No one had a good husband!” not only the participants from China, Russia, and Japan, but also those from South Korea nodded along and laughed. Indeed. In a history marked by colonization and war, men could not play the role of a dependable husband. They were drafted as laborers or soldiers by the state. Frustrated men often became tyrants who tortured their families. Women who had been ignored became the breadwinners as well as caregivers to save their families in those difficult times.

“I did whatever I could!” one woman said. When they lost everything in war and disaster, women, especially mothers, still managed to save their families and raise their children. “By doing any kind of work — whether it was man’s work or woman’s work,” they took root in an unfamiliar foreign land. When the distribution system collapsed, they gathered in black markets and traded goods, crossing the border despite the legality of doing so. Even when the country collapsed, women protected their families in whatever way they could. Thus, they were rightfully dignified and unashamed.

Oppressed by loud men and pushed around by people of high education and status, women could not speak freely at official events. Their life stories were regarded as private lamenting and were not respected as historical facts. Women, accustomed to the reality of discrimination, remained silent in an authoritative setting. But at these “equal dialogue” meetings, where the participants did not criticize or evaluate each other, they divulged the stories that they had kept in their hearts. The women's meetings were passionate and lively.

“Neither the country nor the family matter to me anymore. These days, I come first. It feels so good!” These were the words of a woman who lived under the pressure of multiple layers of responsibility. They talked about love and sex that still made their hearts flutter and described new dreams and plans. One woman confided about her affair long ago, and someone revealed her recent decision to get a divorce. Although they lived in different times and circumstances, they all sympathized with one another’s life stories as women and looked back on their own lives with fresh perspectives.

The life stories of women who crossed many borders were told in various accents and tones. They were the herstories of countless individuals and families that were ignored and cut out of national history. For many Koreans who lived in the era of colonization, division and the Cold War, the transnational migration that crosses borders imposed by the state power was a survival strategy. These women’s stories will finally enable us to complete the national history just like jogakbo is created by linking scraps of cloths in various colors and shapes.

If the Bank of Korea were to issue a 100,000 won bill in the future, I hope it will include an image of the beautiful and tenacious Jogakbo. It will help to do justice to the women of Korea in addition to the portrait of the noblewoman and 16th-century artist Shin Saimdang that now graces the 50,000 won bill.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/8317138574257878.jpg) [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father![[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms? [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/3617138579390322.jpg) [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 2Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 3Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan

- 4[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 5[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 6Opposition calls Yoon’s chief of staff appointment a ‘slap in the face’

- 7Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76

- 8New AI-based translation tools make their way into everyday life in Korea

- 9Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 10Korean government’s compromise plan for medical reform swiftly rejected by doctors