hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Guest essay] Let not the deaths of hundreds of thousands of laborers be in vain

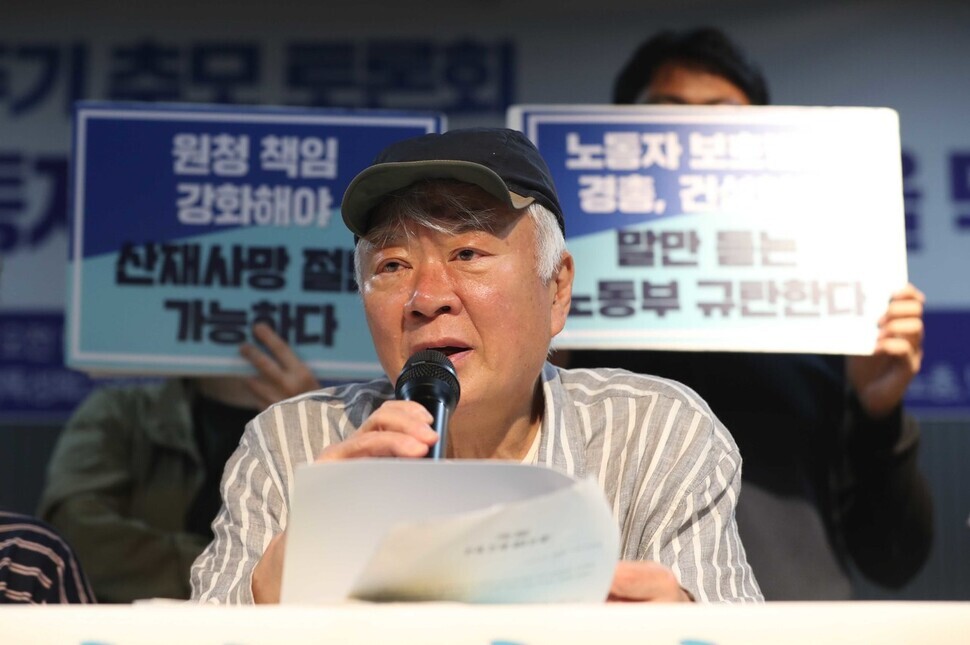

※ Editor’s note: Friday marks the one-year anniversary of the implementation of the Serious Accidents Punishment Act. Labor groups and businesses are still butting heads, the former saying that the law is not being properly enforced, the latter arguing that it has no effect in reducing industrial accidents. Author Kim Hoon, who has been vocal about the issue of industrial accidents (dying or being injured while at work), contributed this piece to the Hankyoreh.

The Serious Accidents Punishment Act defines serious industrial accidents as “accidents involving one or more deaths.” This definition is what determines the procedure for and severity of punishment and sanctions entailing serious industrial accidents.

Right now, businesses are demanding that the definition of serious industrial accidents be changed to “accidents involving two or more deaths.” It’s impossible to know whether businesses will push for their demand until their goal is accomplished, but one thing is clear: The fact that they are demanding such a revision of the law so openly explains why the issue of industrial accidents has become so difficult — if not impossible — to resolve.

The demand that the definition for serious industrial accidents be changed to denote “two or more deaths” demonstrates an underlying view on humans which perceives the lives of laborers as a number indicating expenses and quantifies death in order to do accounting with it. One death is not frivolous because it’s singular, and two deaths are not grave because they are plural. As tragic as it is to say, accidents involving single deaths happen everywhere every day, all year, leading to yearly cumulative deaths of over 2,000 and then 2,200.

The view that single, individual deaths are so trivial as to not require accountability and the death of laborers should not obstruct corporations from seeking profit enables this kind of demand to be made with impunity. This barrier has stymied any and all steps to remedy such fatal industrial accidents.

Even according to government statistics, only 3% of all industrial accidents involving death last year involved two or more deaths. Hence, if serious industrial accidents are defined as those involving two or more deaths, corporations will be able to shirk responsibility for 97% of industrial accidents involving the death of laborers.

The claim that big corporations enjoy a superior position vis-a-vis small and medium-sized businesses, subcontractors, and laborers because they provide for the entire nation, and that eradicating obstacles hindering them from seeking profit and engaging in free competition will increase their profits, leading to more jobs, employment stabilization, increase in pay, and the dawn of paradise has flaunted its tidy logic, becoming a veritable religion in our society. But uniformly applying this logic akin to divine providence to the painful nooks and crannies of the world turns economics into superstition. The world is not as simple and clear-cut as science.

The demand to change “one or more deaths” to “two or more” equals the legislation of such superstition.

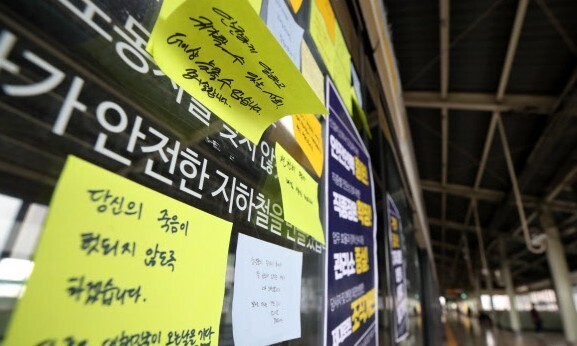

The Serious Accidents Punishment Act did not achieve any results throughout the past year. Industrial accidents involving death increased, and liable business owners were not punished. The government and corporations did not possess the will to realize the spirit of the law from the get-go, and judicial authorities did not apply the law proactively. Corporations did not invest to increase safety. Corporations multiplied their legal spending in order to protect themselves judicially, lobbying politicians in order to nullify a law that already didn’t work.

This lobbying effort was quite successful, leading the government to destroy the foundation of law by making “improvements” aimed towards “self-regulation,” not punishment. The government also announced that it would “improve” who receives punishment, how severe those punishments can be, and how sanctions are meted out. If this law is “improved,” the legal provisions are likely to reflect corporate demand even if “one or more deaths” doesn’t literally change to “two or more deaths.”

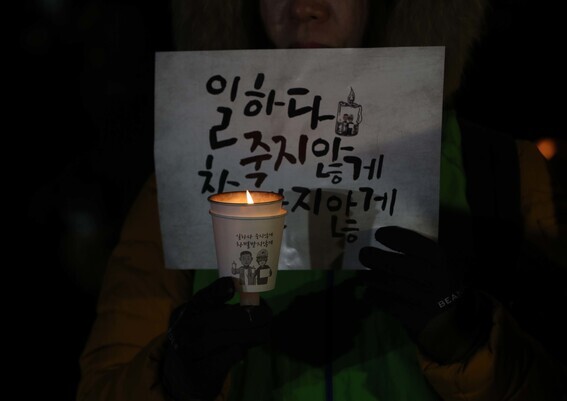

“Industrial accident” is not an abstract phrase. It describes barbaric scenes in which people who go to work to put food on their plate end up getting stuck in between objects, causing their body to crush and scatter (Guui Station accident), having their head and body separated and get all mixed up with coal dust (Taean thermal power plant Kim Yong-gyun accident), and falling from a high altitude, their internal organs and brain spilling onto the ground.

People who narrowly escaped death are abandoned in misery, crippled for life and unable to return to work. By telling forces demanding “one or more deaths” to be changed to “two or more deaths” to resolve the issue through “self-regulation,” the government is merely showing that it sorely needs self-regulation as well.

Industrial accidents and accidents involving death have become incurable endemic diseases in South Korea’s corporate landscape, and these endemic diseases have spread extensively in our society ruled by the superstition of profits. Hoping for this issue to be resolved through entrepreneurship growing on its own within corporations seems like naïve, wishful thinking.

This is not the country countless young people who gave their lives to this nation’s democracy envisioned.

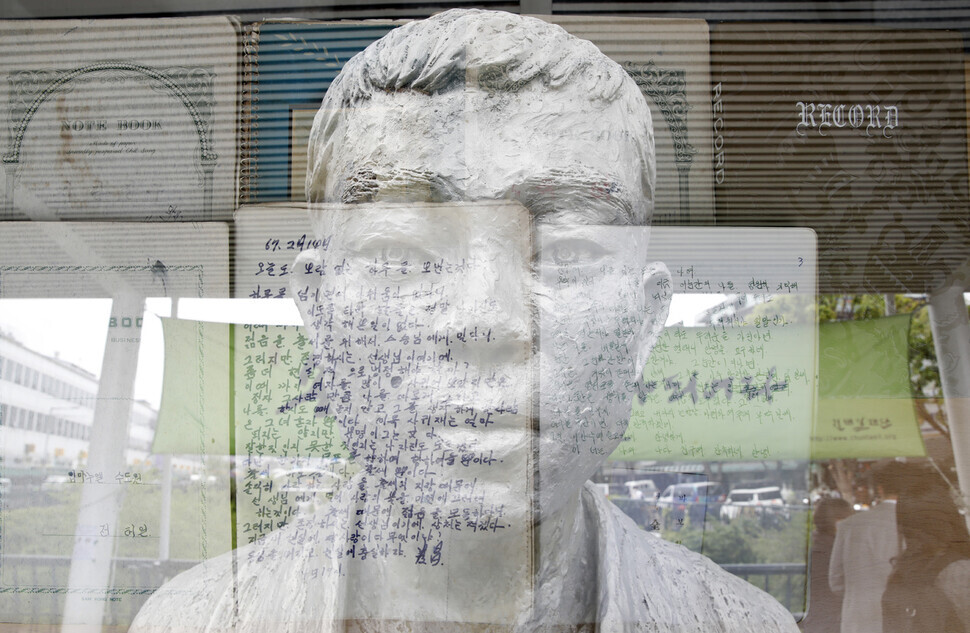

On Nov. 13, 1970, on the road in front of Pyeonghwa Market in Cheonggyecheon, Seoul, Jeon Tae-il shouted while his body burned in flames, “Uphold the Labor Standards Act.”

That a young man who aimed to reform labor’s slavery-like reality had to die crying respect for the law is a tragic paradox of that era. Half a century later, I emulate that paradox: Uphold the Serious Accidents Punishment Act.

With his last breath, Jeon Tae-il also shouted, “Let not my death be in vain.”

I emulate that shout and say again: Let not the deaths of hundreds of thousands of laborers be in vain.

By Kim Hoon, author

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 3[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 4[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda

- 5S. Korea, Japan reaffirm commitment to strengthening trilateral ties with US

- 6All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 7After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 8US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 9[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 10Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76