hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] Would Moon recount Kim Gu’s acts for independence and unification as against God’s will?

By Kang Man-gil, professor emeritus at Korea University and author of The Pain of Division and History of Prospects for Unification

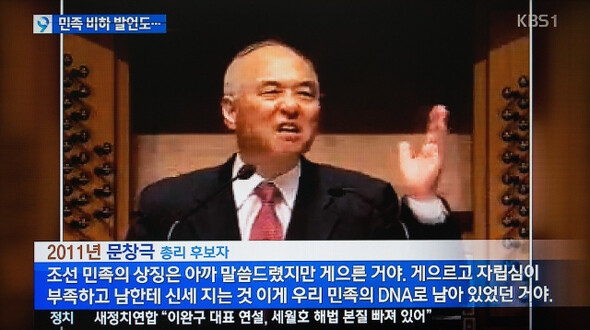

Now that I am well past one decade out of my work on the front lines of research and education regarding Korea’s modern and contemporary history, I have resolved to avoid throwing my two cents in on every issue that surfaces. However, the country has been abuzz recently with stories about how the person who is slated to become the second most powerful in the country after the President allegedly talked about Korea’s occupation by Japan and division into North and South as being “God’s will.” I have not had the opportunity to verify these statements with the man himself, but if his ideas and words are what the news says they are, then I feel that I must say something as someone who has studied and taught Korean contemporary history.

As a specialist in history, I am going strive to ground my statements about Korea’s history in concrete facts. Let’s begin with the issue of the Japanese occupation being God’s will. In point of fact, Korean Empire’s soldiers, who were forcibly dissolved by Japanese imperialists in 1907, numbered at around 8,000. The Japanese Imperial Army’s own statistics places the figure of Korean volunteer patriot fighters who risked their lives to stop Japan’s occupation of Korean territory at 140,000, of whom 20,000 to 30,000 lost their lives in battles that year. In terms of historical perspective, there is a question not about the “will of God,” but whether the Japanese imperialists’ control of Korean territory is to be seen as the either result of the 1910 Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty or the failure of the volunteer army campaign.

If one is going to say that the half-century of Japanese imperial rule was the result of the Annexation Treaty rather than the volunteer patriot fighters’ anti-colonial war failure, then this would mean that Japanese rule was not an invasion or occupation, but instead a lawful government. In turn, the Korean people’s struggle for independence against that rule becomes classified, unjustly in my opinion, as an illegal act of resistance against a lawful governing power. Indeed, the military dictatorship of Park Chung-hee, a former officer in the Japanese empire’s Manchurian puppet state who came to power in a coup that deposed a democratically elected government, never did specify the illegality of Japanese imperialists’ half-century of forcible rule over Korean territory when he pushed through the 1965 Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea.

In 2010, the 100th anniversary of the “annexation,” conscientious individuals in both countries drafted together a declaration nullifying the Annexation Treaty, but without the two governments joining, this action did not have any real effect. If the Japanese occupation was God’s will, then the declaration by these minor figures would never have any true validity. Moreover, one imagines that even if the two governments were to also declare the treaty invalid, it would somehow be in defiance of God’s sacred will.

Indeed, I do not think Moon would have been able to present Japan’s forcible rule over Korean territory as God’s will, as he has now a half-century ago, even had Park’s military dictatorship not traded it for a few hundred million dollars when he forced through the Treaty on Basic Relations. As someone who has spent a lifetime studying and teaching Korean history, it leaves me dumbfounded at how meaningless a historical education can be.

If one thinks that the Japanese occupation was God’s will, one could also hold the opinion that the division of Korea after liberation and the fratricidal Korean War were also the will of God, considering that the peninsula would have gone communist if had not been divided and a unified government had been established. Indeed, facts show that in the chaos that followed liberation, there were some collaborators who betrayed their nation to support the Japanese during the colonial occupation, and who were afraid that they would be brought to justice if the leftists took control of a unified country. It is also true that, for those people, it was extremely fortunate that the government of Syngman Rhee was established in half of the country, pardoning their treacherous support of the Japanese.

History makes clear, however, that left and right were not the only options for a unified government after liberation, since there were also a considerable number of people attempting to set up a government that brought the two sides together. In modern Korean history, there is no denying that Kim Gu was a rightist, even among the right wing leadership. However, even Kim changed the Korean provisional government into a coalition government of left and right in preparation for liberation, after he foresaw that liberation was imminent after the Japanese Empire provoked the war in the Pacific. Kim’s view was it was only natural that they would build a single country together after liberation though the leftists and rightists were rivals inside the independence movement.

Seeing that the liberated nation was in jeopardy of being divided, Kim Gu, who was a preeminent independence fighter as well as a Christian, and Kim Kyu-sik, also a preeminent independence fighter as well as an elder in a church, braved numerous difficulties to cross the 38th parallel into North Korea. Would their attempts to set up a unified government be understood by a younger Christian as defying the “will of God?” Kim Gu started out as a royalist, so loyal to the crown that he killed a Japanese soldier who he thought had assassinated Queen Min, but later became a republican and a Christian, faithfully guiding the provisional Korean government until liberation. It was Kim Gu’s contention that the U.N. had allowed the Korea to be divided into two countries despite promising to make a single country, and he continued to protest until he was assassinated. Kim Kyu-sik, despite being a Christian leader and a graduate of a U.S. university, did not work for independence in the safety of the distant land of U.S. (unlike someone else we could mention), instead dedicating his life to the cause of independence on the ground in China, where he was on the run from the Japanese security forces.

Today, there is another Christian who thinks that the motherland that these two endured so much for was subjected to a forced colonization of the Japanese imperialists, and later a bloody civil war?both of which were inevitable. If the Japanese occupation was the will of God, the patriots who laid down their lives for the liberation of the motherland were defying the sacred will of God. If the division of the country was the will of God, Korea must remain split into two as a powder keg of the Far East and one of the places in the world with the greatest risk of war until that will is fulfilled. Today, this person is about to become the second most powerful figure in the country. While this is embarrassing, I find myself really wondering what these two figures would say, if they could see what was happening today.

It makes sense for there to be people with all kind of opinions in the world. However, if it is true that this appointee thinks that both the failures of history and the successes of history are all the will of God, it is only too clear that he must not be appointed to a major position in government at a difficult time such as this. To put it bluntly, he could simply place all of the responsibility for governing on the will of God instead of on his own ability.

The views presented in this column are the writer’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those of The Hankyoreh.

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 4US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 5[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 6[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 7Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 8All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 9More South Koreans, particularly the young, are leaving their religions

- 10John Linton, descendant of US missionaries and naturalized Korean citizen, to lead PPP’s reform effo