hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] Labor law tumbles in favor of mean-spirited employers

Once again, a company has put pressure on a married couple to resign from their jobs. The wife, who was about to give birth, went on pregnancy leave after her doctor expressed concerns about the fetus’s weak movement. This left the husband to put up with pressure to quit by himself.

The wife had been working in management, but after returning from her pregnancy leave, she was reassigned to the butchery department. Picking up heavy chunks of meat and using a sharp knife to chop the bloody chunks into various cuts brought the wife, who had given birth not long before, to tears. Even so, she received full points on her customer service satisfaction review not once but twice.

A few months later, the wife was reassigned to financial services once again, but she was placed on standby. Since there were no open desks, she had to sit in an extra chair in front of the executive offices.

In the end, the husband informed the company that his wife was resigning, and the company wrote up the letter of registration and even signed it on his wife‘s behalf. After a lot of deliberation, the couple made up their minds to fight the company, but the challenges awaiting them will be even tougher than the ones they have faced thus far.

After South Korea was hit by the Asian financial crisis in 1997, this kind of behavior was quite common. One insurance company that employed 88 couples forced one spouse to quit in 86 of those couples - and most of the spouses who quit were women.

These employees filed a lawsuit asking for their termination to be invalidated, but the courts’ rulings were inconsistent. In the end, the Supreme Court found that the terminations were inappropriate, but the primary reason it gave was not that wives had generally been forced to resign but rather that the resignations had not reflected the employees‘ actual intentions.

Recently there was uproar about the way a company in Changwon, South Gyeongsang Province treated an employee who was on standby. When a certain employee refused to resign voluntarily, the company relocated him to a seat in front of the storage lockers next to one of the office’s walls. After several days without being given any work, he was relocated to a round table.

After going to work in the morning, this employee had to sit in his seat and just stare at the wall all day long. He had to obey a number of behavior rules, such as no personal phone calls, no games or texting on his smartphone, no using the internet, no personal reading material and no studying foreign languages. He was also told that he would be reported to his supervisor if he left his seat for more than 10 minutes at a time.

The employee asked the local labor board for relief from an unreasonable standby assignment, but his petition was denied. The board concluded that the assignment was actually not unreasonable.

“Standby assignments are defined as personnel decisions, while disciplinary action is defined separately in the collective agreement or the workplace rules,” the board said by way of explaining why it “could not conclude that this is illegal or a clear departure from the company‘s discretionary authority over personnel decisions.”

The board’s argument was far-fetched.

Article 23 of the Labor Standards Act, which places restrictions on dismissal, states that “an employer shall not, without justifiable cause, dismiss, lay off, suspend, or transfer a worker, reduce his/her wages, or take other punitive measures [. . .] against him/her.” It would be appropriate to regard the standby assignment in this case as corresponding to the “transfer” or “other punitive measures” mentioned in the law.

A standby assignment that is not disciplinary in nature would mean, as the phrase suggests, placing an employee on standby for a short period while the company is carrying out standard personnel assignments. A standby assignment such as this one, however - one that is clearly detrimental to the employee - obviously qualifies as a disciplinary action.

The problem is that the people in South Korean society who have the authority to make the decision in such cases do not interpret labor law properly.

Labor legislation is one of the best examples of social law in South Korea. In contrast with civil law, which is based on the principle that all citizens are equal before the law, social law is based on the principle that equality can also be achieved through an unequal application of the law.

This is the same reason that when a walker on a tightrope leans in one direction, he must hold out his balancing fan in the opposite direction. If he always held the fan in the middle, in some strained effort to be fair, he would immediately tumble off the rope.

Very few of South Korea’s jurists have studied labor law, since they have not regarded it as being necessary for success. The subject was not covered in the bar exam, and it was an elective in law schools and even at the Judicial Research and Training Center.

As an inevitable result, judges have assessed labor issues according to the formal equality of civil law rather than according to social law, the area to which they in fact belong. Such judges wrongly believe that it is “fair” to assume that the employer, who has the authority to give someone a standby assignment, and the employee, who has to receive a standby assignment, are in a formally equal position.

In what direction ought we to hold out our fan?

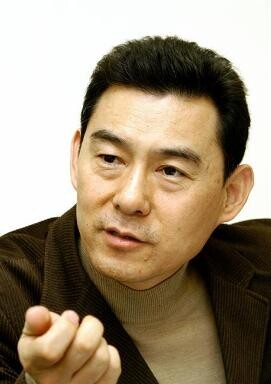

By Ha Jong-gang, dean of the labor college at SungKongHoe University

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 2N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 3Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 4Kim Jong-un expressed ‘satisfaction’ with nuclear counterstrike drill directed at South

- 5[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 6[Cine feature] A new shift in the Korean film investment and distribution market

- 7[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 8[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 9[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 10Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government