hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

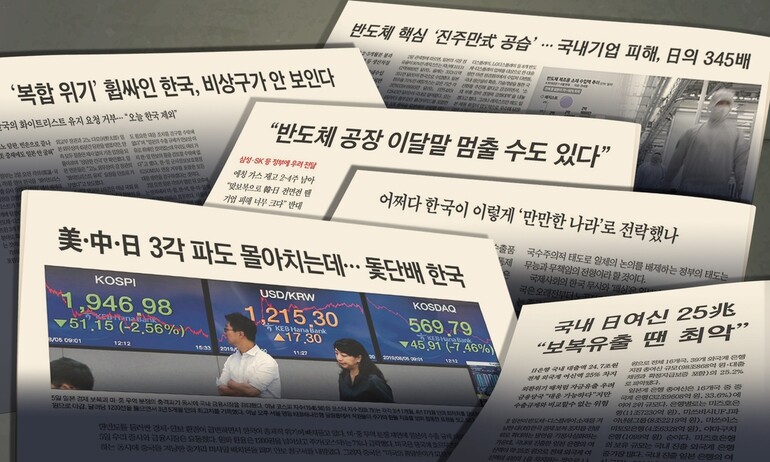

[Column] S. Korea’s economy is no longer that fragile

The front-page headline on the July 6 issue of the Hankyung, also known as the Korean Economic Daily, said, “Semiconductor plants might shut down by the end of this month.” During a meeting with high-ranking government officials, the newspaper reported, CEOs of semiconductor manufacturers said they only had a two-to-four week supply of etching gas and other materials and expressed concerns that their factories could go idle at the end of the month. It’s not clear if the CEOs actually said that, but at any rate those semiconductor factories haven’t shut down. The CEOs now view the dispute with Japan as a blessing in disguise and are urging their staff to treat the crisis as an opportunity.

It’s true that the Abe administration’s economic retaliation, coupled with the escalating trade conflict between the US and China, presents a major challenge to the South Korean economy. But predictions that this will precipitate an unprecedented catastrophe on the level of the 1997 Asian financial crisis are really going too far. The South Korean economy isn’t that fragile.

Let’s step back from the rumor mill and take a hard look at the facts. South Korea reached a per capita gross national income (GNI) of US$31,734 in 2017 (according to statistics updated in June 2019), becoming the seventh country to join the “30-50 club,” referring to countries with a population of at least 50 million and a per capita GNI of at least US$30,000. By the end of July, our foreign reserves amounted to US$403.1 billion, ranking ninth in the world. That’s a 20-fold increase from the Asian financial crisis in 1997, when the reserves stood at US$20.4 billion. At the end of March, we had a short-term debt ratio of 31.6%, much lower than the ratio of 286% before the Asian financial crisis. The credit debt swap premium, an indirect measure of the risk of a sovereign default, has gone up over the past few days, but on Aug. 7, it was still very stable, at 34bp. Our net foreign assets totaled US$436.2 billion at the end of March, the highest they’ve ever been. Our national credit rating, as assessed by Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s, is only two steps away from the top of the scale, and two steps higher than China’s and Japan’s. These rating companies reportedly gave high marks to South Korea’s economic and fiscal fundamentals.

Now let’s compare South Korea with Japan. South Korea’s 2018 gross domestic product (GDP) was US$1.72 trillion dollars, while Japan’s GDP was nearly three times greater, at US$4.97 trillion. The decisive factor here is that Japan’s population is about two and a half times larger than South Korea’s, but that’s still a big difference. But that gap is being rapidly narrowed. Since 1990, South Korea’s GDP has increased by 520%, while Japan’s has only grown by 60%. The change in the per capita GNI has been even more rapid. By 2018, South Korea had a GNI of US$33,434, which was 81% of Japan’s, at US$41,340. Last year, South Korea overtook Japan in electronics, a key industry for both countries, becoming the world’s third largest manufacturer in the field, after China and the US. The value of South Korea’s production output shot up by 54% in five years, while Japan’s moved in the opposite direction, sliding by 11%.

Abe administration’s provocations prompted by fear that S. Korea is catching up

Many analysts believe that the Abe administration’s provocations are prompted by fear that South Korea is catching up to Japan. According to this view, Japan is striking a blow at South Korea’s key semiconductor sector with the hope of extinguishing a driver of economic growth. But Japan has miscalculated. Now, unlike the past, a head-on collision between the two countries would be fatal to Japan, as well.

Amid all this, rumors are circulating that Japan might even impose financial retribution, an unlikely prospect. There are calls to kowtow to the Abe administration now, before we suffer even more harm. Does it really make sense that profit-driven financial companies would call in loans from customers just because Abe told them to? Any firm that did so would be branded as a dishonest broker, ruining their reputation in the international financial market. Even so, some are stirring up fears by spreading rumors about funds being leaked. Such self-defeating behavior is exactly what the Abe administration wants.

Undoubtedly, the South Korean economy faces a number of problems. Over the past few weeks, Japan’s economic retribution has unveiled the vulnerability of our parts and materials industry. Furthermore, our economy as a whole is overly dependent on semiconductors, while leading industries such as automobiles, shipbuilding, and steel are losing their competitive edge. Meanwhile, the industries that should be driving new growth haven’t managed to gain traction. There’s also a severe imbalance between exports and domestic demand. Over time, South Korea’s demographic structure, which is being reshaped by societal aging and the low birthrate, will place an increasing burden on the economy. This stack of structural challenges makes the recent uptick in our economic slowdown even more worrisome.

But every country has its own economic issues. We need to be dealing with our issues systematically, through comprehensive measures that have been carefully framed, and we must avoid creating a panic or engaging in groundless criticism of our economy. That’s what Japan’s far-right politicians and press do. If we don’t respect ourselves, no one will.

By Ahn Jae-seung, editorial writer

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 3Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 4[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 5Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 6Japan says it’s not pressuring Naver to sell Line, but Korean insiders say otherwise

- 7S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 8[Column] Unsettling moves by the UN Command lay way for Korean involvement in Taiwan

- 9[Reporter’s notebook] In Min’s world, she’s the artist — and NewJeans is her art

- 10[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol