hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

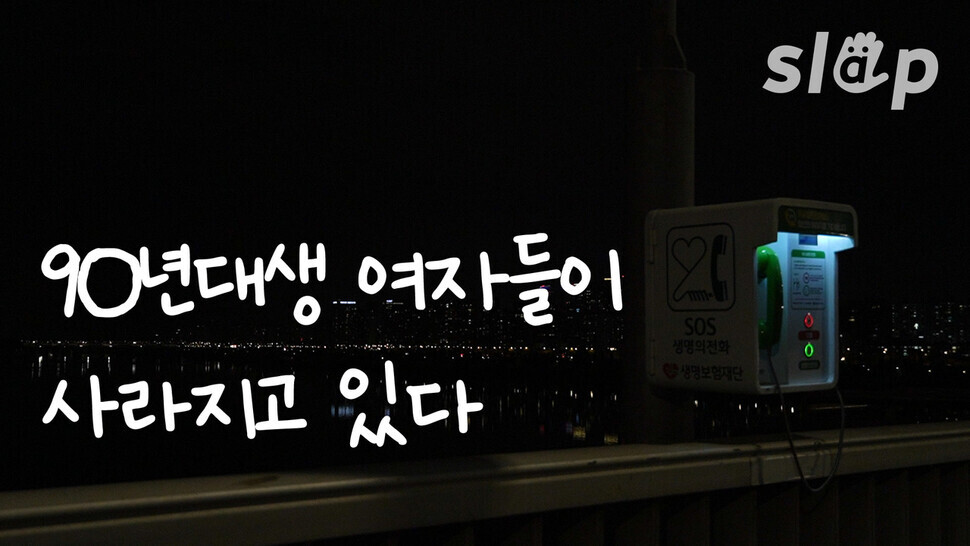

[Reporter’s notebook] The silent massacre continues

According to information submitted to various National Assembly lawmakers by the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) during the last parliamentary audit, one in three South Koreans who attempted suicide between January and August of this year amid the COVID-19 pandemic were women in their 20s. The number of women in their 20s who committed suicide between January and June was also up by fully 43% from the same period in 2019. For the past month, there have been reports of sharp increases in the number of women in their 20s seeking suicide counseling, their rate of suicide attempts, and the number of actual suicide deaths.

My name is Lee Yu-jeong, and I work in the digital media department, where I produce video content for the gender media channel Slap. After seeing the data on suicide among young women, I became curious as to who these women are and why they feel they have no other option but to take their own lives. A person’s suicide is the result of a complex mention of various factors and personal circumstances that we have no way of knowing individually. But I sensed that if there has been a rise in the number of people born around the same time who have taken their own lives, there might be some social factors at play. What was it that pushed them over the edge to their deaths?

There was one other indicator during the first half of this year that worsened alongside the female suicide rate. According to Statistics Korea figures on employment trends, the employment for women in their 20s declined sharply across all ages and economic segments during the months of March and April, which saw a severe economic blow shorting after the COVID-19 pandemic erupted. During periods of economic crisis, we tend to see marked declines in women’s employment — and in the case of the COVID-19 crisis, women from the generation just embarking on their careers were the first ones forced out.

The suicide rate among South Korean women in their 20s is at a worrying level right now. Jang Soong-nang, a professor at the Chung-Ang University Red Cross College of Nursing, published a report last year analyzing suicide rates released by the World Health Organization (WHO). The results showed the suicide rate among women born in 1996 to be fully seven times higher than it was when those born in 1951 were in their 20s. A rising trend was also observed with a rate roughly five times higher for women born in 1982 and six times higher for women born in 1986 than for those born in 1951.

Reductive notions of women as being “biologically emotional and weak-willed” and a person’s 20s being an “inherent unstable period” are of no help in addressing this issue. Similarly, no one can yet reach any simple conclusions as to how much the issue of suicide among 20-something women has been impacted by the pandemic, or whether the issue has to do with the unique socioeconomic environment they face in South Korean society.

It may be that the high suicide rate among young women provides the most factual indicator showing the social status they occupy and the resulting sense of helplessness. This is a generation of women who watch their peers die and wonder whether they can safely reach an old age together, while talking about saving up the money to travel to Switzerland for euthanasia when a suitable time comes. How did it come to be that the word “death” has become such an intimate part of the lives of South Korean women born in the 1990s, including my friends and me?

Women born in 90s see as “hope” for relieving effects of population agingAny approach to preventing these deaths needs to start with first truly recognizing the problem for what it is. In a special estimate of the future population published last year, Statistics Korea predicted that the birth rate would rise once women born in the 1990s reach their 30s, which is considered the main childbearing age group. But while the state has been harboring these vain hopes that position women born in the 1990s as “salvation” for the low birth rate, the women themselves occupy a precarious position between life and death. This two-dimensional perspective that still sees women as “vehicles for childbirth” failed to detect the danger signals that women in their 20s have been sending out.

The generation born in the 1990s also shows the larger imbalance in terms of the sex ratio. That ratio, which represents the number of male children born for every 100 female ones, stands at 116.5 for those born in the 1990s. This means that as it became possible to know a child’s sex ahead of time, the opportunity to be born was preferentially given to male children by a large margin. Women born during the 1990s — a period when many children were not carried to term simply because they were female — have grown up, tragically, to take their own lives.

Since the Nov. 12 posting of a video on this issue titled “The ‘Silent Massacre’ Starts Again,” there has been an outpouring of accounts from over 1,000 “survivors,” sharing everything from shock and astonishment to stories about the moment they decided to end it all. The largest number of messages expressed support and solidarity, urging young women to “hang in there” and “survive together.” Some also accused the video of imbalance, pointing out that it was focused solely on the suicide rate among women in their 20s while ignoring the persistent reality of the male suicide rate being much higher.

But the video was not made simply as part of a “contest” to see who is suffering more. It was done to call new attention to the seriousness of the situation with the recent sharp rise in suicides among 20-something women, and to suggest that we should be trying now to find out what is behind it and establish measures for prevention.

The rapid increase in suicides among women in their 20s is a trend that dates back more than a decade. It may be that the relevant indicators and statistics are not yet sufficient. For now, we have no clear answer as to why the suicide rate among 20-something women should be rising. But I hope this will be an occasion for studying and analyzing the meaning of this signal more closely. I hope that those who have held on to hope even amid despair can survive with us, and that we do not have to see any more of them passing away. And I believe that this is the path to salvation for all of us in this dangerous world.

By Lee Yu-jeong, video content producer

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 3Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 4[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 5For survivor, Jeju April 3 massacre is a living reality, not dead history

- 6[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 7Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 8[Special Feature Series: April 3 Jeju Uprising, Part III] US culpability for the bloodshed on Jeju I

- 9[Column] America must frankly own up to role in tragic Jeju April 3 Incident

- 10‘My mission is suppression’: Jeju blood on the hands of the US military government