hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] US should listen to its allies for its national security strategy to succeed

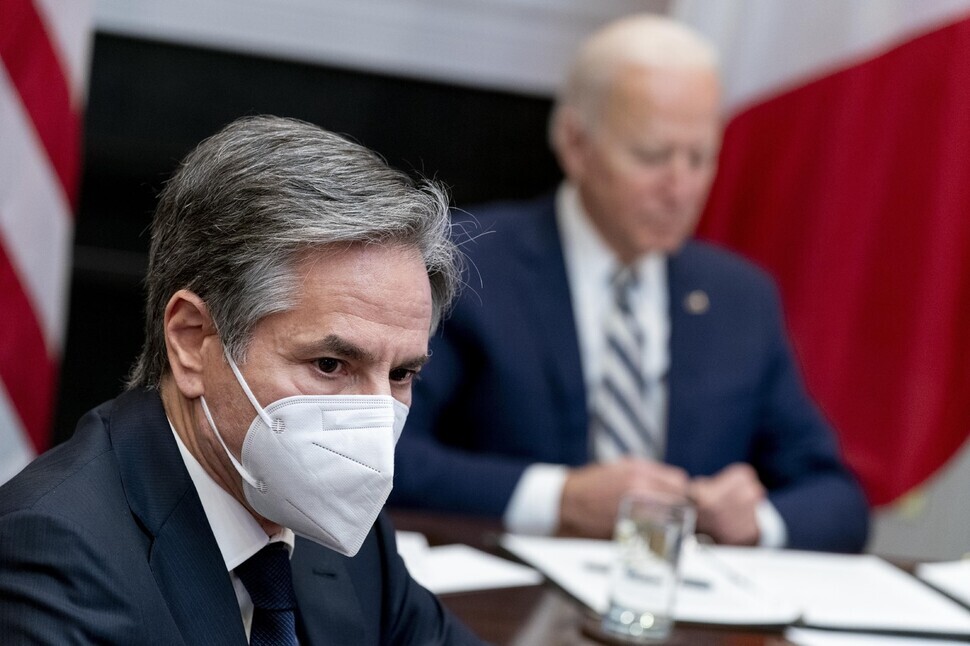

I had mixed thoughts on March 3 after seeing the provisional national security strategy guidelines announced that day by the US administration under President Joe Biden, along with the eight foreign affairs priorities stated by Secretary of State Antony Blinken the same day.

Although it was all dressed up with rhetoric about rebuilding democracy, restoring alliances, returning to diplomacy and promoting international cooperation, it gave the impression of lacking an objective understanding of the reality and practicable strategic guidance.

Most crucially, the US seems to be confused about what it wants to achieve and what it is actually capable of achieving.

The idea of starting at home as it rebuilds the democratic values and institutions that are the source of its strength is both a necessary step and something that the US is able to do on its own.

What isn’t clear, however, is how it plans to go about resolving the wide range of supranational threats, the challenges posed by China and Russia, or the Iran and North Korea issues. A closer examination shows the Biden administration offering just one potential solution: responding in a way that takes advantage of the “alliance assets” that predecessor Donald Trump so grievously undermined.

But the interests and situations of the key alliances singled out by the Biden administration — namely NATO, Australia, Japan and South Korea — can’t be aligned with those of the US.

To begin with, the European Union struck a nerve with the US when it started off Biden’s inauguration year of 2021 by reaching terms on an investment agreement with China after seven years of wrangling. Ultimately, the Biden administration won’t be able to accomplish anything without its allies’ cooperation.

Also worrisome is the front-and-center focus on “value diplomacy,” emphasizing values such as democracy and human rights.

When the US enjoys an overwhelming power advantage, this sort of value diplomacy takes on an inclusive quality, offering a public good to the international community. But at times like now when US leadership has been weakened, the overconfidence and clear distinctions of “good” and “evil” can easily come across as arrogant.

Now is a time that calls for more realistic perceptions and a more pragmatic approach from the US, not an aggressive value diplomacy push.

It also stands to create friction, not just with strategic rivals but also with allies, if the same kind of arrogant attitudes that we’ve seen from the US government and public on South Korea’s recent adoption of legislation prohibiting the distribution of propaganda leaflets in North Korea also rear their heads on the Korean Peninsula denuclearization issue or other issues in East Asia.

One striking thing about the Biden administration’s national security guidelines is that they jettison the traditional distinction between foreign and domestic policy; instead, national security strategy is tied to domestic policy.

Reading as an extension of Biden’s election slogan of “foreign policy for the middle class,” this reaffirms that the objective of foreign policy is not to benefit a privileged few but to promote quality of life for all Americans, including workers and members of the middle class.

While this could be seen as a legacy of Trumpism, the attempt to link security strategy to the lives of the community at large is a healthy approach that can’t simply be condemned as populism.

South Korea also needs to make similar efforts, making foreign affairs an everyday agenda that the public can get behind rather than a high-level, abstract agenda for an elite few. It will be difficult for either the US or South Korea to establish much momentum behind foreign policy that does not attract support in domestic political terms.

For example, the value of the South Korea-US alliance should not be treated as a sacred cow but made into something that the public keenly senses and supports.

What we have seen to date is merely a provisional framework, and it looks like more time will be needed to see how the Biden administration’s new national security strategy is reflected on the Korean Peninsula and in East Asia. But if alliance assets represent a key strategic means, then the Biden administration will need to listen more closely to what South Korea is saying as a “linchpin” in East Asia.

After butting heads for some time, South Korea and the US have finally concluded their negotiations on defense cost-sharing. But advancements in denuclearization talks and inter-Korean relations will be even more important.

South Korea is the single most interested party in terms of the North Korean nuclear threat, and it possesses the greatest abundance of intelligence on the North. It is capable of offering the most accurate assessments of Pyongyang’s behavior patterns and intentions. When it comes to Korean Peninsula issues, the Biden administration could afford to “outsource” duties to its South Korean allies.

When Blinken and US Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin arrive in South Korea Wednesday to visit the Demilitarized Zone and check up on the Korean Peninsula’s security situation, I recommend that they also listen to what their South Korean allies have to say — at least when it comes to peninsula issues such as North Korea’s nuclear program and inter-Korean relations.

By Kim Seong-bae, senior research fellow at the Institute for National Security Strategy

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Life on our Trisolaris [Column] Life on our Trisolaris](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0505/4817148682278544.jpg) [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

[Column] Life on our Trisolaris![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2New sex-ed guidelines forbid teaching about homosexuality

- 3[Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- 4S. Korea discusses participation in defense development with AUKUS alliance

- 5Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 6Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 7[Reporter’s notebook] In Min’s world, she’s the artist — and NewJeans is her art

- 8Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 9Japan says it’s not pressuring Naver to sell Line, but Korean insiders say otherwise

- 10[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press