hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Seoul travels] Fall foliage in the city’s theater district

If there are times for filling, there are also times for emptying. I’m listening to a performance of the adagio second movement of Mozart’s “Piano Concerto No. 23,” performed by the French pianist Helene Grimaud. The music flows like an exotic scene from one of the movies I used to watch at the Institut Français when it was still located in front of Gyeongbok Palace’s Geonchun Gate.

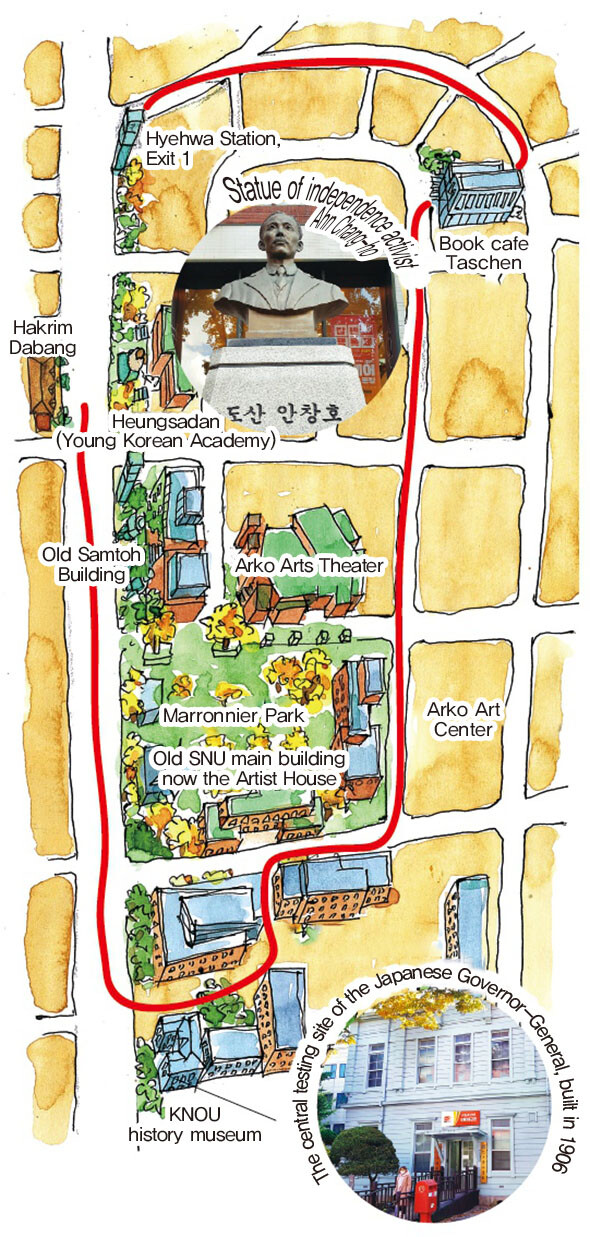

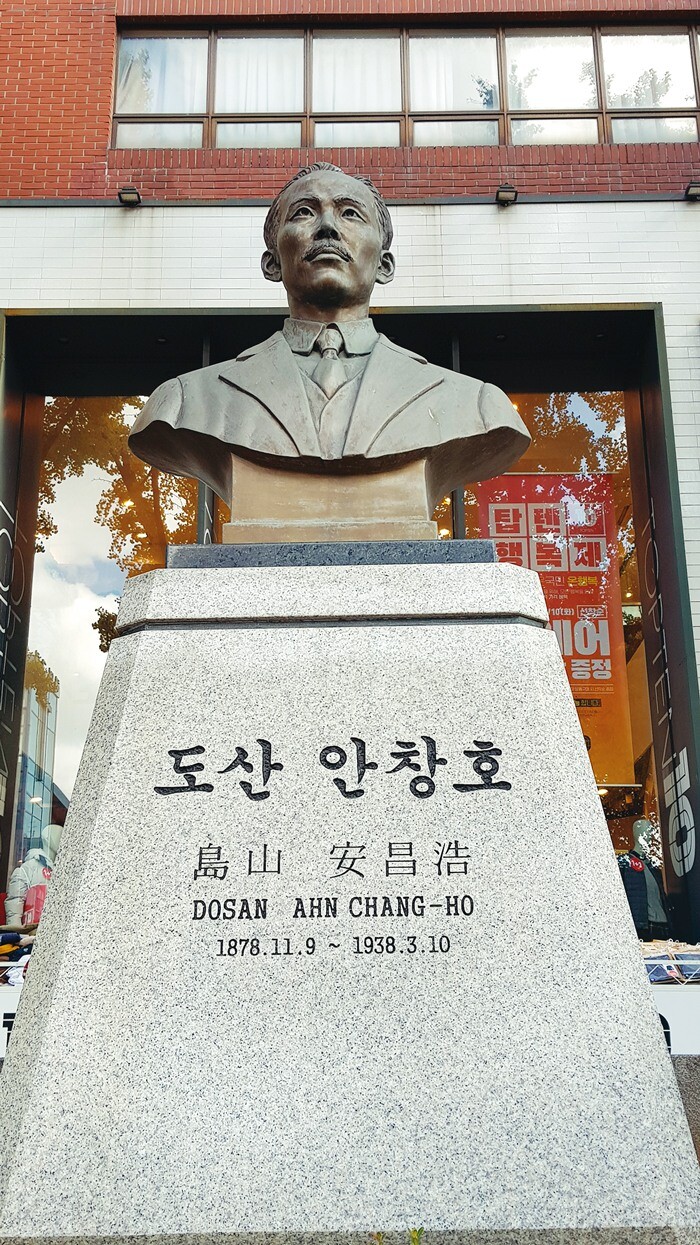

I took the subway and disembarked at Hyehwa Station to see the ginkgo leaves in Seoul’s Daehakro neighborhood. It was my own way of saying goodbye before letting the late autumn give way to winter. Exiting the station, I saw one of the walls there plastered with notices about musicals and small theater performances. Another wall had a signboard in front of it sharing information about an “emergency support project” for the performing arts in general amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Right away, I could see that this had been among the hardest-hit areas since the pandemic began. As you leave Exit 1 and head right, you encounter a street called Dongsung Road, which is packed with university music department buildings and venues such as small theaters for musicals and plays. Small theaters also lie concealed among the side streets that radiate in both directions from Daehakro into the surrounding Hyehwa neighborhood. Official figures put the number of large and small performance venues here at over 160 — making it a true mecca for the performing arts in South Korea. At least in numerical terms, it’s a suitable scale for its aims of becoming a “performance street” along the lines of New York’s Broadway or London’s West End.

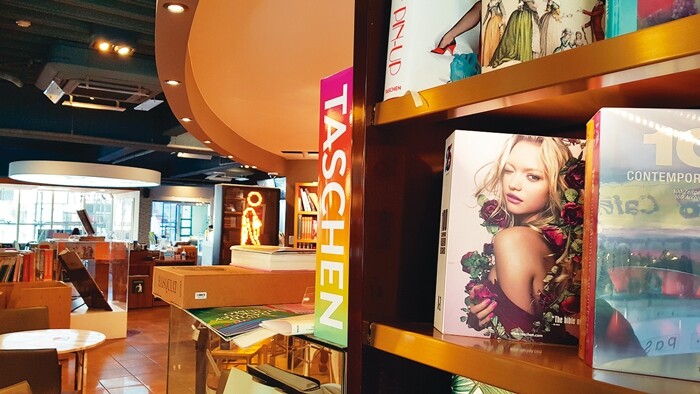

But with the dismal weather and the pandemic continuing into the long term, it has faced difficulties regaining its past vitality. As I followed Dongsung Road to where it meets the street known as Daehakro 12-gil, I stopped by Taschen, a cafe known for its collection of books on art and architecture. It too was quiet, perhaps because of the disruption with construction work on the building. The area known as Marronnier Road is a curved section centering on Dongsung Road as it sweeps toward Daehakdo’s residential areas, along with the street of Daehakro 8-ga within that. On Saturdays and Sundays, it becomes a “car-free road” and a pedestrian’s paradise.

The heart of Daehakro lies in Marronnier Park — a plaza of color. The air may have been chilly, but fortunately the autumn paused in its distant journey to welcome me with a wave of gold. The deep yellow leaves falling from the chestnut (“marronnier” in French) and ginkgo trees at the park’s center combined with the red brick buildings around them to create a fantastic landscape. A major part of this came from the mind of architect Kim Swoo-geun. The park was built on the site left behind when the Seoul National University liberal arts college relocated to the Gwanak campus in 1975; Kim had the idea of building red brick art museums of performance venues around it, and the structures began to go up in 1981.

After a redevelopment project in 2010, it took on its current form, which centers on the Arko Arts Theater and Arko Art Center. To one side of the park, the old SNU main building remains along with a monument. It is the only remaining structure from SNU’s former Dongsung campus, and the basis for the “Daehak-ro” name (literally meaning “university road”). It is now known as the Artist House.

Next to Marronnier Park is the Korea National Open University (KNOU) building, with European-style structures visible to the right of its main entrance. This structure was built during the Korean Empire period in 1906 and was later used for the central testing site of the Japanese Governor-General of Chosen. Distinctively, it was built with German-style feather boarding to allow rainwater to run off easily. As befits the only remaining wooden structure from the Korean Empire days, its inner corridors and staircases are also made of wood. It is now used as the KNOU main building.

Daehakro once the center of Korea’s intellectual community

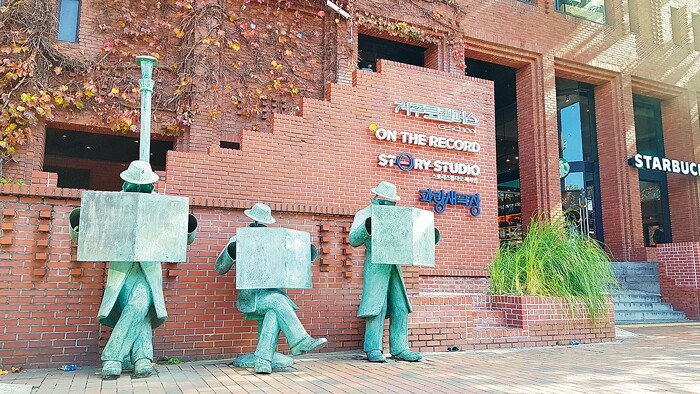

Turning back from here toward Exit 2 of Hyehwa Station, you can see a red brick building with strikingly large windows. Used until recently as the Samtoh building, this too is the work of Kim Swoo-geun. It was once the home of Nandarang, the very first South Korean coffee chain — playing a pivotal role in promoting a modernized (as opposed to tearoom-based) coffee culture. Having sat for a written test on Nandarang’s second floor and having worked for Samtoh, I also attended numerous editorial meetings at that coffee shop with such luminaries as the poet Kim Hyeong-yeong, the children’s book writer Jeong Chae-bong, and future Hankyoreh Chief Editor and Kyunghyang Shinmun President Goh Young-jae. Having also been the backdrop where I drank tea with the monk Venerable Beopjeong, authors Choi In-ho and Kim Seung-ok, and poet Sister Lee Hae-in, it could fairly be called a “salon” of sorts for intellectuals.

Beyond this, it was also a place of intense waiting and fighting back my own feelings of anxiety and inadequacy from day to day. While I only worked there for a short time, the Samtoh building was like a way station for my future. Today, there is a Starbucks where Nandarang used to be — a case of the flavor of local color and culture being taken over by global capital.

Gijoam, the udon restaurant where Choi In-ho used to go for lunch with Kim Jae-sun, former chairman of Samtoh, doesn’t seem to be around anymore. The restaurant had been renowned for udon made by hand with a technique learned in Japan’s Sanuki region. But when I tried making a call, I got a message saying the number is no longer in service.

A wooden staircase next to a pharmacy catty-corner from Samtoh leads to Hakrim Dabang, a historic cafe that first opened in 1956 and still operates today. This is where the city's intellectuals often gathered during South Korea’s democratization movements.

As I walk back out to Daehakro, the wind is blowing, and the sun is about to set. It’s a time of day when I’m reminded of the song “On the Street,” by the folk band Dongmulwon (meaning “Zoo”).

“The deep darkness piles up on the street like fallen leaves. / Only the chill wind passes me by. / Somehow everything feels like a dream. / I turn my collar up and try to smile, / but I keep picturing you walking away. / As my tears fall, I look back once more.”

The novelist Albert Camus once said that fall is a second spring, when every leaf becomes a flower. Spring is beautiful, of course, but not any more than fall. The season epitomizes the truth that we don’t realize how valuable something is until it’s gone.

With the fallen leaves behind me, I find myself reflecting upon myself. Who am I? Where did I come from, and where am I going?

The English word “me” is pronounced the same as the Chinese character for beauty (美). Does that mean I’m supposed to look for something that sets me apart, a beauty unique to myself?

That’s both a classic question of the humanities and one of the reasons I find myself enjoying the humanities and the arts more and more as I get older.

Even so, it’s not easy to say goodbye. I wonder how much older I need to be before I stop stumbling over those words.

By Son Kwan-seung, travel writer

Edited by Seoul& editorial board

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 3S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 4Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 5Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 6[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 7OECD upgrades Korea’s growth forecast from 2.2% to 2.6%

- 8Inside the law for a special counsel probe over a Korean Marine’s death

- 9Japan says it’s not pressuring Naver to sell Line, but Korean insiders say otherwise

- 10[Exclusive] Hanshin University deported 22 Uzbeks in manner that felt like abduction, students say