hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[News analysis] “Graveyard of Empires” or punching bag of empires?

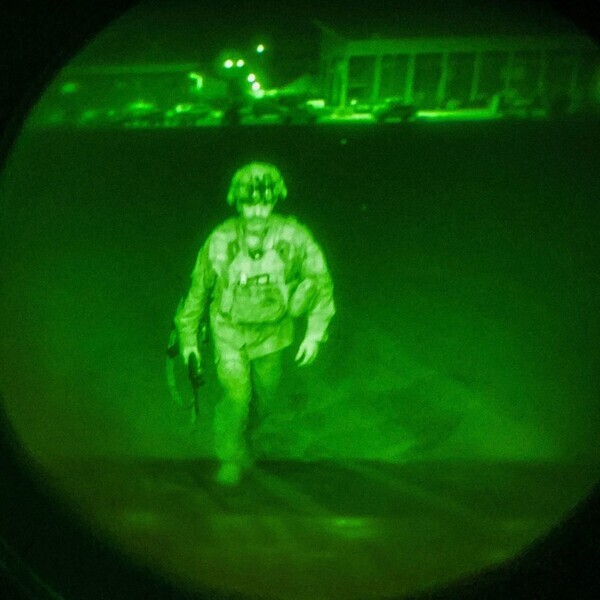

The War in Afghanistan — which has been variously called “the forever war,” “the longest war,” and “the phantom war” — is over.

The war that had lasted for 43 years, since the establishment of a socialist regime in Afghanistan in 1978, was declared over with the withdrawal of US troops on Monday.

Poor and isolated Afghanistan was occupied first by the Soviets and later by the US, its allies, and NATO member states. There have also been interventions by Islamic states such as Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. Muslims from around the Islamic world converged on Afghanistan to wage jihad, meaning “holy war.”

South Korea sent troops as well, which led to the kidnapping of a group of Christian missionaries in 2007. Two were killed and the rest were released after more than forty days in captivity.

Those 43 years of war in Afghanistan were a volatile mix of the geopolitical ambitions and miscalculations by two empires — the US and the Soviet Union, those empires’ attempt to justify their ambitions in terms of the Western concept of “regime change,” the armed resistance of the Afghan people and other Muslims, and self-interested interventions by neighboring countries, leading to astonishing contradictions and reversals.

First, let’s examine the imperial ambitions and miscalculations of the great powers.

Afghanistan is often called the “graveyard of empires,” an epithet that dates back to the Great Game, or the British and Russian Empires’ struggle for hegemony over Central Asia in the 19th century. As the Russian Empire swiftly expanded into Central Asia, the British were seized with “Russophobia” — the fear that the Russians would sweep south toward the Indian Ocean, threatening British holdings in India.

Britain preemptively occupied the critical crossroads of Afghanistan in 1839, but three years later, there was a revolt by local tribes that led to the annihilation of the British occupying force. Only one person returned alive of more than 17,000 soldiers and camp followers.

The British ended up launching two more invasions of Afghanistan, despite the fact that Russia had neither the will nor capacity to threaten India. These British miscalculations, inspired by its imperial ambitions, provoked a “chicken game” that prompted Russia to also threaten the surrounding areas. It wasn’t until the collapse of the Russian Empire in 1919 that the British granted Afghanistan independence as a neutral state.

Afghanistan was dragged once again into the morass of war through the imperial ambitions and miscalculations of the Soviet Union, the successor of the Russian Empire. The Soviets launched a military intervention out of concern that the collapse of the socialist regime established with its support would have ramifications on its possessions in Central Asia.

Next was the US. Just as the British Empire, as a Western maritime power, had sought to block Russia from reaching Afghanistan despite having few strategic interests there, the US also sought to put the occupying Soviets in a bind. Partnering with Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, the US organized not only Afghan locals but Muslims from around the world to form the mujahideen guerillas, who would wage jihad against the Soviets.

The mujahideen did indeed force a Soviet withdrawal, but they were also the precursors of the Islamist movement that viewed the US as the enemy. That eventually led to the formation of the Al Qaeda terrorist organization and the 9/11 terrorist attacks, creating circumstances that forced the US to launch its own invasion of Afghanistan.

That was when the US rashly sought to reset the order in the Middle East by toppling the Iraqi regime led by Saddam Hussein. Once the Taliban had been deposed in Afghanistan, the US redirected its resources to the Iraq War. The US’ neglect of rebuilding Afghanistan laid the groundwork for the return of the Taliban.

Second, there was the failure of “regime change” based on Western values. In fact, the War in Afghanistan was provoked by a response to the radical reforms of the socialist government. The issue of women’s rights, which has become a cause célèbre in the international community since the Taliban returned to power, actually dates back to the socialist government’s attempt to overturn the tribal order in the country.

The socialist government declared that women were free to choose their marriage partners, abolished dowries, and instituted mandatory education for women in an attempt to promote female literacy, while also pushing through land reforms. Those changes galvanized opposition not only among the vested interests in the Afghan tribal system but also among ordinary people in rural parts of the country, leading to an uprising.

Even today, 70% of the Afghan population live in tribal structures in nonurban areas. The modern reforms advanced by both the Soviets and Americans during their occupation of the country further inflamed divisions and disparities between city and country dwellers.

Those superpowers focused support for their reforms in the cities and launched air raids and drone strikes on recalcitrant parts of the countryside, causing the death of many innocent people. That set the stage for the Taliban’s return to power. That also sowed the divisions that have caused members of the urban middle class and highly educated women in particular — the primary beneficiaries of efforts to modernize the country — to fear the Taliban’s return and seek refuge in other countries.

A third factor has been a shift in the world order. While the Soviet Union began the war, it fell apart while the war was still underway, leading to the end of the Cold War. For a time, it seemed that a US-led unipolar order was taking shape, but the growth of the Islamist forces that the US had fostered in the War in Afghanistan lured the US into an ongoing entanglement in the Middle East. That enabled the rise of China and its sharp rivalry with the US.

The US spent a total of US$2.31 trillion in Afghanistan. Adding the costs incurred by the Soviet Union and NATO member states who took part in the fighting brings us close to US$4.1 trillion, the amount of money the US spent in World War II (converted to current values).

Despite all the money poured into the country, Afghanistan’s GDP in 2020 was only US$20 billion, just 0.5% of all those war expenditures. Afghans continue to face famine and poverty, with a per capita income of just US$500.

During the twenty years of the US’ war in Afghanistan, 170,000 American service members and Afghan civilians lost their lives, and more than 2.6 million people were displaced. Including the Soviet occupation brings those tallies to over 2 million dead and 10 million people displaced. And the ultimate outcome was the Taliban’s return to power.

Carter Malkasian, who served as a senior aide to the chairman of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, asks the following question in his book “The American War in Afghanistan.”

“The Taliban were far from good. They oppressed women, hollowed out education, and silenced free speech. Our intervention did noble work in these spheres. But that good may not balance out the violence, death, and injury. Without our intervention, Afghans would have been deprived and oppressed, but alive. [. . .] Did we liberate, or oppress, the Afghan people?”

That raises another question. Is Afghanistan really the graveyard of empires, or is it a victim of empires on the march?

By Jung E-gil, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 2Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 3[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 4No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 5[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 6[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 7Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 8Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 9Marriages nosedived 40% over last 10 years in Korea, a factor in low birth rate

- 101 in 5 unwed Korean women want child-free life, study shows