hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Scientists deliberately gave 36 volunteers COVID – here are 3 major insights from the experiment

Results were recently shared from the world’s first COVID-19 “human challenge trial,” which took place in the UK in February 2021.

A human challenge trial involves deliberately infecting participants with a virus to see how their bodies respond to it. It’s intended to develop effective disease prevention and treatment approaches — but it’s also the subject of ethical debate, as participant lives could be endangered during the testing process.

A British team led by researchers from Imperial College London conducted the human challenge trial on 36 healthy female and male adults aged 18 to 30 who had not been vaccinated or previously infected. For the study, they closely observed the process from the start of the infection until the virus was no longer detected.

According to findings published by the researchers in Research Square, a platform of pre-print articles for the international journal Nature, participants began showing symptoms two days on average after exposure to the virus.

The virus used in the trials was taken from patients infected early on in the pandemic, before variants had begun to emerge. The researchers introduced small quantities of virus into the trial participants’ noses, after which they closely observed the infection’s progression in a hospital over a two-week period. Two of the participants were excluded from the study for showing an antibody response prior to the virus’s introduction.

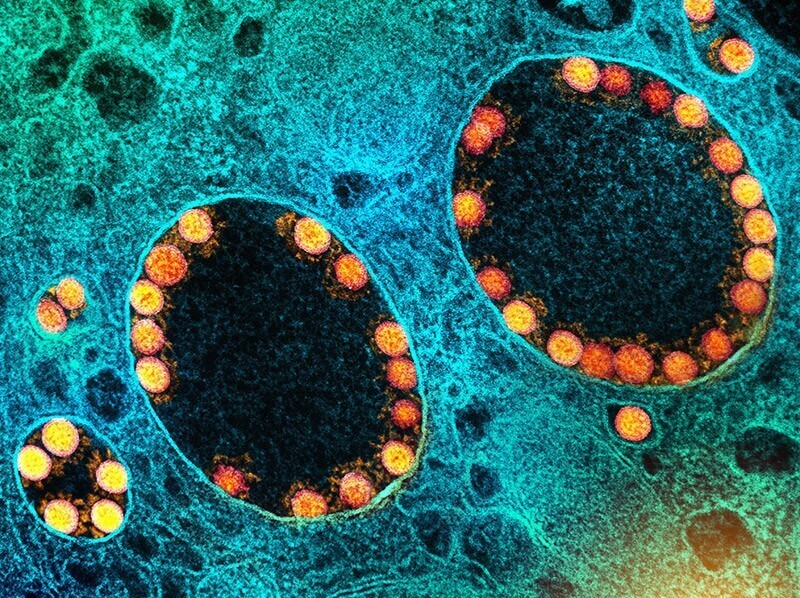

Symptoms began in the throat, with viral quantities reaching their peak five days after infection. The largest amount of virus was detected in the nasal cavity.

Half of the participants (18 people) became infected, with 16 of them developing mild to moderate cold-like symptoms including congestion, a runny nose, sneezing and a sore throat.

Some of the participants showed symptoms of headache, muscle and joint pain, fatigue and fever. Thirteen of them reported temporarily losing their sense of smell, although all but three of them recovered their normal smell capabilities within 90 days. The remaining three also reported that their symptoms were continuing to improve three months later.

No symptoms were detected in the participants’ lungs.

Given the difficulty establishing that a patient has been infected with COVID-19 until symptoms begin to appear, the human challenge trial is significant in that it provides the first detailed data on the body’s response immediately following exposure to the virus. The results announced three major findings from the trials.

The first was the briefness of the incubation period.

For the 18 participants who were infected, the incubation period averaged 42 hours — far shorter than the previous estimates of five to six days. Once the incubation period had passed, a rapid rise was observed in the amount of virus detected on swabs taken from the patients’ noses and throats.

Second, the most active proliferation of the virus occurred in the nasal cavity.

The virus first began reproducing notably in the throat. Patients showed positive test results for the virus in throat samples 40 hours after infection, and in nose samples 58 hours after infection — but the maximum virus quantities were far higher in the nose than in the throat.

This suggests a greater risk of the virus being shed from the body through the nose rather than from the mouth. It also means that those wearing masks need to cover both their nose and their mouth.

Similar virus levels were also observed in asymptomatic patients.

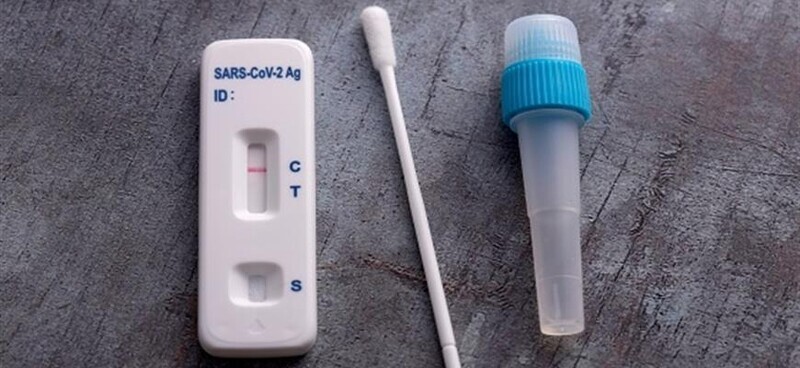

The third finding concerned the usefulness of rapid antigen tests, also known as lateral flow tests.

The researchers found that lateral flow tests — in which a swab is inserted into the nose to take a sample — played an effective role as indicators to determine whether transmissible virus is present. Throughout the infection process, lateral flow test findings closely matched the findings of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

But their precision was also found to be lower toward the beginning and end of the infection period, where levels of virus tend to be lower.

“LFA [lateral flow assay] was highly reliable in predicting the disappearance of viable virus and therefore also underpin ‘test to release’ strategies,” the researchers said.

They also noted that “lateral flow results were strongly associated with viable virus and modeling showed that twice-weekly rapid tests could diagnose infection before 70–80% of viable virus had been generated.”

The study’s primary investigator, professor of infectious disease Christopher Chiu, said that while lateral flow tests may be less sensitive during the first or second day after infection, they could play a major role in deterring the virus’ spread if used repeatedly.

The researchers said the study provided a model for human challenge trials. In a press release, they noted participants in the historic trial at London’s Royal Free Hospital showed only mild symptoms, indicating that the study could safely be performed again.

They also concluded that it had laid the groundwork for future studies to test COVID-19 vaccines and treatments.

“First and foremost, there were no severe symptoms or clinical concerns in our challenge infection model of healthy young adult participants,” Chiu noted.

The amount of virus introduced to the participants was the minimum capable of causing an infection. It was similar to the quantity found in a single droplet within the nasal cavity when transmissibility is at its highest.

The researchers are planning future efforts to learn why some of those exposed to the same quantity of virus were infected while others weren’t. The journal Nature suggested the possibility that other forms of coronavirus that cause the common cold may have resulted in immunity against COVID-19, or that participants possessed powerful innate immune capabilities and did not require additional immunity.

Once conditions allow for it, the researchers are further planning to conduct a human challenge trial for the Delta variant in vaccinated patients. They are currently working to acquire samples of the Delta variant for testing.

Nature also noted that some researchers had raised questions about whether the research findings were significant enough to justify the potential risks to participants.

Meagan Deming, a professor of virology at the University of Maryland in Baltimore, pointed out to the journey that over a quarter of the participants infected with the virus experienced problems with smell or taste for up to six months or more.

“It sounds like this is the most serious risk that materialized. This is the one to keep an eye on,” said Northwestern University bioethicist Seema Shah.

The other researchers quoted by Nature suggested that the study’s findings were a “promissory note” for scientific and social benefits from the human challenge trial — but that those benefits are not yet apparent.

Participants in the COVID-19 human challenge trial were paid 4,565 pounds, or roughly US$6,200, each.

By Kwak No-pil, senior staff writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0517/8117159322045222.jpg) [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later

[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later![[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0516/7417158465908824.jpg) [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence

[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence- [Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation

- [Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- [Column] How to win back readers who’ve turned to YouTube for news

- [Column] Welcome to the president’s pity party

- [Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line

- [Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- [Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

- [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

Most viewed articles

- 1[Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- 2[Exclusive] Unearthed memo suggests Gwangju Uprising missing may have been cremated

- 3[Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- 4Xi, Putin ‘oppose acts of military intimidation’ against N. Korea by US in joint statement

- 5[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner t

- 6‘Shot, stabbed, piled on a truck’: Mystery of missing dead at Gwangju Prison

- 7China, Russia put foot down on US moves in Asia, ratchet up solidarity with N. Korea

- 8Victims’ families refuse late apology by Oxy Reckitt Benckiser

- 9Constitutional Court declares act that denies unions by university professors is unconstitutional

- 10Another chaebol heir caught smuggling liquid marijuana into South Korea