hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Feature] Very much alive, Koreans ponder their enshrinement at Yasukuni

"It makes no sense," said Kim Ji-gon, 89. Elderly and hunched over, he shook with rage, muttering strings of words that were hard to catch. Kim is enshrined at controversial Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo. The shrine memorializes those that died on the side of Japan during conflicts since the Meiji Restoration in the mid-1800s, and includes many class-A war criminals.

Kim’s name at the shrine is written as "Kanemura Takeshida," a reflection of the banning of Korean names during the latter half of the Japanese colonial period (1910-1945). Many Koreans either chose to enlist or were forced to serve in the Japanese military.

Kim’s enshrinement - as in all of those honored at Yasukuni - comes for his supposed martyrdom on behalf of the Japanese emperor.

"It’s complete nonsense," he spat.

"Well, what are you going to do about it?" scolded his wife, Gwak Wol-rye, 83.

Kim first learned of his enshrinement at Yasukuni 15 years ago. A call came from a member of the Association for the Bereaved and the Survivors of the Pacific War.

"I was riled by the appalling news," he told me in our interview. "A man like me, who is still alive and kicking!"

At the time he learned of the situation, he implored his sons to expunge his name from the shrine. In 2005, his grandson, Son Jeong-gu, finally made the journey to Yasukuni Shrine.

The response that Son received from the administrators presiding over Yasukuni Shrine was that they would merely change his grandfather’s status to "confirmed alive." Though the Yasukuni overseers saw this as a sufficient remedy, Kim demanded that all records of him be removed whatsoever from the shrine.

The story of Kim’s "departed" spirit being enshrined is a long one. He was born in 1919, in Wollong-ri, Sijong-myeon, Yeongam-gun, South Jeolla Province. After graduating from a Pyongyang vocational high school at the age of 18, he found a position as an airplane maintenance technician in the city, working for the Japanese military. His first month’s wages totaled 35 won. Afterwards, he was transferred twice, first to Hamheung and then to Manchuria. In 1943, he was transferred once more, to the Philippines.

The G.I.s came like a tidal wave upon the Philippine island of Luzon on January 9, 1945. "I fled into the mountains to escape the American air attack," he recalled. There, communication with the Japanese military’s headquarters was broken off, leaving his superior officers to conclude he had died in the line of duty. The records of Yasukuni Shrine list him as "perishing in combat on the island of Luzon on May 30, 1945." He was enshrined 14 years afterwards, on April 6, 1959.

Kim was most likely not the only survivor to be mistakenly enshrined at Yasukuni. There are some 21,000 Korean names listed there, most of whom were enshrined some 15 years after the end of the World War II without any notification of or approval from their surviving kin. It was only some ten years ago that reports of Koreans’ enshrinement at Yasukuni were first widely made known in South Korea. Researcher at the Northeast Asian History Foundation Nam Sang-gu explained, "Ten years ago, the issue came to light through reports by organizations for the bereaved." Many of the descendants of those enshrined were mortified by the discovery. As if it were not enough that their forebears had been forced to join the Japanese army, now their corpses were no doubt turning in their graves, "honored" as they were for supposedly fighting on behalf of the Japanese empire. This was unacceptable to many of the Korean bereaved.

On June 29, 2001, 55 of the bereaved filed a lawsuit in a Tokyo court to remove the nameplates of their kin from the shrine, but the Court rejected the motion, ruling that "as the religious corporation of Yasukuni was the one to enshrine them, the government has no word in the matter."

The bereaved filed another lawsuit on February 26, 2007, and are currently awaiting hearings.

With help from the Truth Commission on Forced Mobilization under Japanese Imperialism, Hankyoreh21 was able to able to obtain a list of 11 enshrined Koreans still actually alive. Some refused an interview outright, and others turned us down gruffly, saying it would be "burdensome." Of the 11 survivors, Kim Ja-yeong, Jim Byeong-gi, Heo Hong-beom, and Kim Hui-jong agreed to simple phone interviews, Nam Cheon-o and Kim Yong-ha were unreachable, Gye Hun-gu migrated to America in the ’70s and was unreachable, and Jye Yun-ok, Kim Ji-gon, Park Won-ju, and Jeon In-pyo each agreed to an interview after much deliberation. Though confirmed alive last December, An Tae-man and Eom Ju-ryeok each passed away over the intervening months. Those interviewed all expressed one common point: in the 62 years since the end of the war, we were the first to interview them regarding their experiences.

A resident of Beolgyo in South Jeolla Province, Park Won-ju was born July 4, 1927. Describing himself as "afraid of forgetting the past," he wrote his memoirs in tiny print. His recollections at times agreed with, and at times contradicted, the records of the Truth Commission and Yasukuni Shrine.

"I applied to the army because of my friendship with the local Japanese mayor, Mr. Yamamoto," he recalled. He was 17 at the time. In his four-page memoirs, he wrote, "In November 1944, I departed Beolgyo by morning train bound for the port of Busan, where recruits like myself were gathered into groups of some 500 divided by home province." According to the information confirmed by the Japanese government, Park died August 10, 1944 in Guam. It would seem Park had mixed up the dates of 1943 and 1944 in his memoirs.

After going to Busan, he passed through Shimonoseki and Tokyo before boarding a boat for an unknown destination at a naval base in Yokohama. After docking briefly at Saipan and departing, at 3 a.m. on February 10, 1944 crewmen began shouting, "There’s a U.S. submarine off the bow!" Awoken from his sleep, Park ran up to the deck. Before his very eyes, two torpedoes were barreling toward the vessel. There were 100 Korean laborers and 300 Japanese sailors onboard. To avoid the torpedoes, the boat took a quick turn, but it was too late. "Gwong!" he wrote, describing the sound. The boat split in half. Standing toward the bow, shrapnel pierced his left eye, and he fell into the black waves.

Blood streamed out of his punctured eye, and he could not open either eyelid. Struggling to stay afloat, a long plank floated his way. Thrown on the defensive by the U.S.’s advance across the Pacific, the Japanese Imperial Navy had begun stocking their boats with 12 footboards to be used as makeshift life rafts in case of disaster. This was one of them. Some 32 men clung to the plank, fighting with all their might to stay above the waves. Attached to both sides of the plank were containers of biscuits, meant to provide rations until rescue. Subsisting on these, they fought for their lives. A Japanese rescue vessel arrived at 7 p.m. that night. Lying exhausted atop its deck after 15 hours of struggle, they gave thanks for their lives. The shrapnel was removed from Park’s eye only after the vessel’s arrival at Guam.

Japan’s position only worsened, however. After arrival at Guam, Park set about digging bunkers and otherwise fortifying his garrison’s position.

"It was so hot I couldn’t think straight. I can’t begin to describe the hardships I went through there."

The Americans landed on Saipan June 15, 1944, and on Guam July 21 the same year. The naval bombardment of the island lasted over a month. Pinned down, the Japanese could not muster much resistance. Park fled into the forest with a few of his comrades. "We foraged for fruits, caught mice and lizards, and stole food from the natives in order to live." Bereft of a barber, much less scissors, for an entire year, his hair grew past his shoulders. Unaware of Japan’s defeat, the hiding survivors lived in the jungle through October 1945. "One day, we found a U.S. magazine in a trashcan. A fellow named Akaki could read some English, and he told us it said that Japan had already surrendered." After some time, Park, too, surrendered to the Allied Forces, returning to his home in Busan after a stopover in a detention cell. His death notice had reached his house before him. Incredulous at his return, his parents at first refused to open the front door for him.

He learned of his enshrinement at Yasukuni on July 11, 2006 through an evening newspaper. The paper listed five people as enshrined yet still alive, and his name was among them. "I was upset," he recalled. Why had a living person like himself become a ghost enshrined? Then there was the problem of money. The Japanese government guaranteed pensions and compensation for the services of those veterans of Japanese citizenship, but Koreans were excluded for reason of nationality. The Japanese government took every means to confirm the fate of Japanese soldiers, and fixed mistakes in the record regarding them as soon as they were uncovered. Meanwhile, the enshrinement of Korean veterans began in 1959. After all, though doling out pensions could be costly, it took little money to enshrine them. The administrators of Yasukuni neither notified nor sought the permission from bereaved survivors. Nor did they so much as investigate the fate of those Koreans who fought for Japan.

Accompanying Hankyoreh21 during the interviews, Japanese reporter Sunami Keisuke asked whether the veterans had even considered at the time of their deployment whether their spirits would be attended to at Yasukuni Shrine. "I had been to Yasukuni Shrine," replied Park. "When I briefly received training in Tokyo, I went there with a fellow soldier. At the time, there were many people, and two fellows from Hamgyeong Province [Ed: now part of North Korea] were seriously injured after being run over by a train." Hailing from colonial Korea, Park had little reason to think he would be enshrined in Yasukuni.

"Japanese people view things a bit differently," said Sunami. For instance, there is the case of Iwai Masuko, who submitted a declaration to the Osaka District Court on April 15, 2002. It read, "recently, people across the nation are expressing their displeasure via lawsuits in regards to the Prime Minister’s visit to Yasukuni Shrine. My husband believed as he went off to fulfill his military duty that I would be there to pay respects to him regularly at the Yasukuni Shrine. Thus, to speak ill of the Shrine is humiliating to me in the utmost."

"Not everyone, but people with lots of patriotism feel that way," explained Sunami. "I can’t speak for Koreans," he continued, "but some Japanese people are very grateful that the Japanese emperor prays for their [lost loved ones] and pays respects to their spirits." Though Shinto is rooted originally in a simple faith of the people meant to bring about peace of mind, with the advent of the Meiji Era, it was promoted as a national ideology in which the emperor was transformed into a god in the form of a man who ruled over the "divine state."

"I cannot help but feel sad knowing one’s son will not return, but knowing that he died for his country, and that his majesty [the emperor] praises his service, my joy is so great as to make me forget all other sad thoughts," reads the June 1939 edition of Japanese magazine "Housewife’s Friend." Though it is odd to think of Japanese mothers shaking off their sorrow and feeling pride in their son’s death, if one recalls the praise afforded to those who were martyred out of devotion to Catholicism, one can begin to understand perhaps. The problem in this case, however, is that these sons died in the act of attacking someone else.

The Koreans enshrined at Yasukuni had no belief in the Japanese Shinto system, much less an understanding of it. They did not even know they were enshrined there.

"Crazy bastards," chuckled Jye Yun-ok, 86, of Jinju, South Gyeongsang Province, "Why enshrine the spirit of someone still alive?"

As for Jeon In-pyo, 84, he doesn’t even know exactly what Yasukuni Shrine is.

Jye enlisted in the Japanese army in the fall of 1943 under some coercion, and caught malaria while positioned at an elementary school in southern Taiwan. "The disease healed, but I pretended to still be sick and thus avoided being shipped off to the Philippines. That’s why I’m still alive. I hated the Japanese military and was despondent about my situation for three years. That’s why I did not receive even a single promotion."

Jeon In-pyo recalled he was fooled by the promise of "receiving 100 won in cash, 100 won being put into savings, and 100 won being sent to [his] family" and enlisted in the army in 1942 at the age of 19. According to the records of Yasukuni Shrine, he perished at Giruwa, New Guinea, on January 12, 1943. In fact, he did suffer a shrapnel wound to his right leg there, losing motility in it. But U.S. soldiers loaded him on a stretcher and took him to the hospital. He regained his freedom after living briefly at a POW detention center in Australia. "I was notified of his death, and performed rites of memorial for him for three years," his wife Jeong Sun-im, 85, recalled. Unable to walk, Jeon never was able to find a regular job.

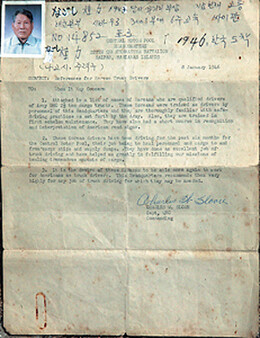

It was only the backyard grave of Gunsan resident Eom Ju-ryeok (1919-2007) that awaited this Hankyoreh21 reporter on a visit to his house. "My father passed away March 12 of last year," explained the deceased’s son, Eom An-seob (59). Among his father’s effects was a letter of recommendation written by a captain Charles Sloan. Captain Sloan wrote something to the effect that Eom Ju-ryeok had been a great help in conveyance operations by driving a 2.5-ton truck for six months, and that he would be a suitable candidate for employment as a truck driver on the U.S. base. Eom An-seob (59) could not understand the English written in the letter. Most likely, neither could his father. As if to ward off the inevitable slippage of memory, the late Eom had written short notes at the top of the paper of things he experienced before his return to his homeland, such as "wound to the head," "navy headquarters," "six weeks of education," "Saipan," "POW," and "arrival in Korea."

Eom’s family now wages a tireless effort to convince the Japanese government to remove his name from Yasukuni Shrine. With his death, however, it is impossible to know how Eom Ju-ryeok himself would think of his enshrinement.

Article by Gil Yun-hyeong

Translated by Daniel Rakove

Please direct questions or comments to [englishhani@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 4[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 5[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 6Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 7All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 8[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- 9[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda

- 10US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters