hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Feature] Are members of Korea's royal family enshrined at Yasukuni?

"I'm not sure...It may well have been the case," said Lee Seok of the fate of his older brother, Lee U. The Hankyoreh21, a weekly newsmagazine, had traveled down to Jeonju's Hanok Village as part of an investigation as to whether any descendants of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) royal family were honored at controversial Yasukuni Shrine in Japan.

"When my older brother Lee died, he was serving with the Japanese army," continued Lee Seok, who is the 11th son of late King Ui-chin. You said something about Yasukuni Shrine? What a vile matter." He gave a dry cough, and said no more. With that, this reporters had no choice but to return to Seoul without any further information.

Other relatives of Lee U gave similar responses. Lee Hye-won, member of the Board of Advisory for the National Palace Museum of Korea and the grandson of King Ui-chin, said "I think I've heard something along those lines before." He continued, "I had heard somewhere that uncle Lee U's spirit was enshrined at Yasukuni, but I had never verified it. It happened long ago, did it not? I don't know much about it."

Together with the Institute for Research in Collaborationist Activities, Hankyoreh21 investigated the stories of those members of the Joseon royal family enshrined at Yasukuni, controversial for its honoring of many World War II class-A war criminals and the inclusion, against families' wishes, of many foreigners who were forced to fight for the Japanese empire.

In the process of the Hankyoreh21 investigation, many of the interviewees responded, "I've heard something like that before," or "I don't really know." Those who did claim to know something of their relatives' fate largely gave testimony based on hearsay. A difficult period in the region's history has thus been relegated to memory's distant past.

The spirits of some 2,460,000 soldiers who fought and died on behalf of the Japanese emperor are worshipped at Yasukuni Shrine as "spirits of protection." Among them are more than 21,000 who came from Korea and 27,000 from Taiwan, both colonies of Japan at the time, regardless of their bereaved’s will or without their bereaved being notified.

On June 29, 2001, 55 of the Korean bereaved filed a lawsuit in a Tokyo court to remove the nameplates of their kin from the shrine, but the Court rejected the motion, ruling that "as the religious corporation of Yasukuni was the one to enshrine them, the government has no word in the matter."

The bereaved filed another lawsuit on February 26, 2007, and are currently awaiting hearings.

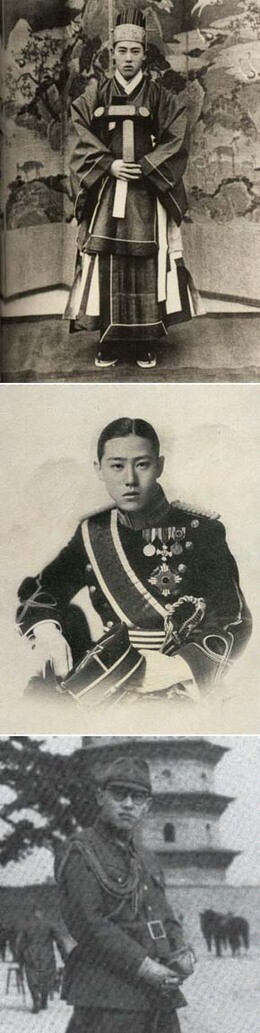

Among the Joseon dynasty's royal family members, there were three in Japanese military service if either with willingness or being forced, including King Yeong Chin (1897-1970), who was the heir of the Joseon dynasty's last emperor but never served, King Yeong Chin's elder brother's son Lee Geon (1901-1991), and Lee U (1912-1945).

Lee U was adopted by Lee Jun-yong, a grandson of Daewongun, who was father of Gojong, the second-to-last emperor of the Joseon Dynasty, serving between 1863 and 1907.

Lee U died on August 7, the day following the dropping of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima. He was stationed there as a lieutenant colonel in charge of education at the Second General Headquarters. The headlines for

Hankyoreh21 and the Institute for Research in Collaborationist Activities thus hit the books. The answer proved suprisingly easy to find. The history of Yasukuni Shrine, originally called Tokyo Shokonsha upon its founding in 1869, was recorded in a three-volume set published on June 30, 1987 under the title, "The 100 Year History of Yasukuni Shrine." On page 506, there is a short record of Lee U's enshrinement:

"Lee U died in battle at Hiroshima on August 7 in the year of Showa 20 [1945]. In October of the year of Showa 34 [1959], he was enshrined...alongside some 45,000 soldiers."

A more detailed file regarding his enshrinement is said to exist, but Hankyoreh21 was unable to obtain it. In addition, Lee's enshrinement at Yasukuni was never made known to academic circles in Korea.

When told of his older brother's enshrinement, Lee Seok responded that "it has already been 62 years since our homeland was liberated, but the fact that I did not know of my brother's spirit being forced into the shrine makes me angry."

In his book regarding the history of the Korean royal family, "Descendents of the Empire," Jeong Beom-jun wrote that, "like his father [King Ui-chin], Lee U was a spirited man who loathed Japan."

Born November 15, 1912, Lee U's mother was Kim Heung-in. He attended Gyeong-seong Preschool starting in 1915, Chongro Elementary School beginning in 1919, the year of the March First Movement, and then went to study abroad at a school for Japanese noble classes. The Chosun Ilbo and Dong-a Ilbo newspapers at the time contain many trifling stories regarding Lee U's life, including "Automobile Carrying Lee U Runs Over Pedestrian," "Lee U Falls Off Horse; Slightly Wounded," "Lee U Pickpocketed in Tokyo," etc. Sanguine and genteel, he was quite the gentleman of his day.

He is described as a rare figure among the Joseon royal family, one who expressed a clear nationalistic consciousness, having declared that "Joseon must gain independence." The words of those who knew Lee in life confirm this. "Descendents of the Empire" introduces testimony regarding Lee U spoken by those who knew him during a program by a Hiroshima broadcast station on September 15, 1988.

Asaka, a classmate from Japan, recalled, "He was deeply intent on Joseon's independence, and so he would strive to never lose or concede to a Japanese person, always trying to be in the lead." Un Hyeon-gung [Daewongun's residence]'s private tutor, Kaneko, recalled, "[Lee U] had a steadfast conviction that Joseon had to gain independence, thus making even the Japanese army officers fear him." Historian Lee Gi-dong wrote an article titled, "Lee U and the Generation of Resistance" for the May 1974 monthly publication "Generation," in which he described in detail Lee U's avoidance of a strategic marriage with a Japanese woman in favor of one with Park Chan-ju, the granddaughter of Marquis Park Yeong-hyo.

Akazawa Sirou's book "Yasukuni Shrine" describes the issues and questions faced by the Japanese in the enshrinement of Lee U. At the time of his death, Lee U was regarded as a member of the Korean royal family with the same status as Japanese royal family members. The official statement by Yasukuni Shrine regarding his enshrinement says "on his death he was a Japanese, so it is natural that he be revered as a spirit who protected Japan."

Pursuing this logic, at the point of his death Lee U had the same status as members of the Japanese royal family, and should thus have been afforded equal treatment to them in death. On October 6, 1959, Yasukuni Shrine accepted the opinion of the Japanese Imperial Household Ministry that royal family members such as Kitashirakawanomiya Yoshihisa and Kitasirakawanomiya Nagahisa" cannot be deified in the same spot as commoners," thus setting aside a separate

Yet Lee U never received such treatment, despite the fact that the Joseon Dynasty royal family was supposed to be treated as equal to its Japanese counterparts after the Joseon Dynasty was forcibly annexed by Japan.

"The enshrinement of Lee U, a royal family member who perished at Hiroshima, became a big issue at Yasukuni Shrine. There was debate as to whether Lee U should also be afforded treatment in accordance with his royal status and the precedent set by the Kitashirawanomiya enshrinements [Yasukuni Shrine]," reads Sirou's account.

After some debate, it was decided that Lee U be enshrined together with the thousands of other soldiers who perished in the war, according to Sirou's book. "It is unclear as to why he was treated differently," the book reads, "but there may have been some sort of signal from the Imperial Household Ministry."

Following the atomic explosion at Hiroshima, Lee U was discovered in the afternoon beneath a bridge, covered in dirt. That night, he was transported to the naval hospital at Ninoshima Island, south of Hiroshima. He briefly regained consciousness there, but passed away the following dawn, moaning in pain and stricken with a high fever.

Before being transferred to Hiroshima, Lee U had reportedly lived at Unhyeon Palace in Seoul, where he forecast a Japanese defeat. He had swallowed a binding medicine so as to feign sickness in an attempt to avoid being sent over to Japan to fight.

Showing a prescience beyond his years, Lee was quoted as saying before heading over to Japan, "I cannot say this to others, but I believe that a Japanese defeat is predetermined. Not only America, but the Soviet Union, too, will be active [after Japan's defeat], and so the liberation of Korea in itself will be a momentous task." The quote comes from Kim Eul-han's work, "King Yeong Chin as Private Person." Seven years later, upon lines originally determined by the U.S. and the Soviet Union, the Korean peninsula would be divided after a devastating war.

Lee U's corpse was transported to Seoul on August 8, 1945 where it was embalmed under the supervision of a medical affairs officer. One week later, Japanese emperor Hirohito declared Japan's surrender. Lee U's funeral was held immediately after the broadcast of the emperor's announcement, at 1 p.m. on August 15 at Gyeongseong Stadium, now Dongdaemun Stadium. It was held in a Shinto-style, offficiated by a Japanese military command stationed in Korea.

In attendance were a youthful widow and two young children. The funeral ceremony was reportedly marked by a devastating sense of loss.

Written by Gil Yun-hyeong and freelance reporter Sunami Keisuke

Translated by Daniel Rakove

Please direct questions or comments to [englishhani@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 4US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 5[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 6[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 7Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 8All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 9More South Koreans, particularly the young, are leaving their religions

- 10John Linton, descendant of US missionaries and naturalized Korean citizen, to lead PPP’s reform effo