hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Interview] ‘Do not follow the U.S. capitalism, treat it as a wicked teacher’

Our misconceptions about Switzerland are that it “makes its money selling cuckoo clocks and cow bells, or that, put nicely, it makes its living on the finance and tourism industry, but that’s just wrong,” Cambridge University Professor Chang Ha-Joon, said recently in Seoul during his summer vacation. During a Hankyoreh interview August 20, he said Koreans need to do away with their mistaken ideas about the rest of the world.

“Switzerland has the highest per capita manufacturing output. It is not making its livelihood off of services. Manufacturing output is 24 % higher than Japan and 2.2 times higher than the United States. It is the most industrialized country in the world and yet we think it depends on services. We Koreans have a lot of misconceptions like these.”

He listed other amusing misconceptions as well: “Panama hats came from Ecuador. The cuckoo clock was invented in Germany. French fries originated in Belgium…”

“It’s a typical misconception that neoliberalism (the market-is-everything-ism) is a widespread trend sweeping the world and that there are no alternatives to it,” Chang said. “When the people who control the world’s ideology repeatedly say that there are no alternatives, most everyone else says it’s impossible to find alternatives, without making an effort to seek them out. They think there are no alternatives because they don’t try to find them.”

Chang pointed to the Swedish model as an alternative to neoliberalism. Sweden boasts more efficient public companies than private firms and achieves both social stability and economic dynamism throughout a compromise between labor and management, Chang said.

Chang also characterized the Korean belief that Americans live in the most affluent circumstances in the world as a myth. “The standard of living in the U.S. isn’t high. Working hours in the U.S. are 10 % to 30 % longer than in Europe. When it comes to purchasing power in terms of working hours per gross domestic product, the U.S. ranks seventh or eighth in the world, which means there are many low-income laborers in the country. In Germany, stores close at 5:00 p.m. But in the U.S., some stores stay open round the clock and many people work into the night. In terms of quality of living indices, such as the crime rate, the infant mortality rate and life expectancy, the U.S. ranks at the bottom among advanced nations,” Chang said. Chang notes there is no reason to follow the U.S. model, dubbed by some economists as the model for neoliberalism. However, if any country were to try and follow the United States, it would be putting itself on a dangerous path, he said.

Chang offered his criticism of South Korean economic policy following the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis. Since then, corporate investment has fallen and unemployment has risen on the back of policies that ordered companies to reduce their debt-to-equity ratio from 400% to 200%, Chang said.

“If a low debt-to-equity ratio were a good thing, Brazil would be at the top of the world. Brazilian companies don’t borrow money and their average debt-to-equity ratio is 50%. Given its national sentiment, South Korea went to the extreme. When the government ordered companies to reduce the debt-to-equity ratio to 200% (following the Asian financial crisis), they cut it to 100%. Even in the U.S. and Britain, the ratio stands at about 150%...,” Chang said.

After the Asian financial crisis, there was a widespread belief within South Korea that neoliberalism was unavoidable and, at the time, many experts said there were no alternatives. Chang’s theories clearly refute those views.

“There is no other country that implements industrial policy as (seriously) as the U.S. The U.S. spends a lot on research and development. South Korea and Japan are billed as government-driven economies, but R&D spending accounts for just 20% of the national budget, compared to 30% in Europe and 50% in the U.S. In mid-1990s, the U.S. government’s R&D budget accounted for 50% to 60% of its total budget and the figure went up to 70% some years after that. The United States is able to remain competitive in the area of technology because research and development are funded by the government,” Chang said.

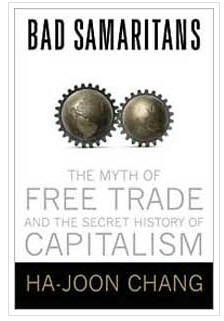

Nevertheless, there is one remaining question. We cannot expect that the “bad samaritans” of the world will change their minds voluntarily. Chang dubs supporters of neoliberalism “bad samaritans,” reflecting the title of his 2007 book. In retrospect, isn’t it true that opponents of the neoliberal orthodoxy are powerless to force the “bad samaritans” to change their way of thinking?

“We have two points to think about. One has nothing to do with the concept of ‘bad samaritans.’ For example, Finland and Norway actively provide aid to less-developed nations. They do not oppose adopting a neoliberalist policy toward less-developed countries. The misconception is that (neoliberalist policy) is the best policy. Of the ‘bad samaritans,’ there may be some who think ‘Ah! This isn’t working,’” Chang said. Those who are more aware probably think neoliberalism is penny-wise and pound-foolish, Chang added. In the long-term, Chang expects that people will realize rich nations need to help poorer ones.

Chang’s powerful analogy and his positive view of government policies for large companies have sometimes been criticized because they overlook the problems spawned by Korea’s family-owned business conglomerates, or chaebol, or because they are in line with the kind of authoritarian rule employed by former South Korean President Park Chung-hee.

Yoo Jong-il, a professor with the KDI School of Public Policy and Management, once said, “I agree with Professor Chang’s criticism of neoliberalism, but is he also underestimating the problems with the chaebol?”

Chang said that the outcome of the recent corruption scandal involving Samsung Group, which has shaken South Korean society, was wrong. The chaebol system has taken an advantage of its division of planning and coordination tasks by coordinating business decisions among affiliates, he said. However, rather than dismantling this structure, Samsung maintained the structure that was in place when ownership of the group was transferred from Lee Kun-hee to his son, Chang said.

Looking ahead, what are Chang’s predictions for the South Korean economy?

“The situation (in Korea) is better than in the U.S., Britain, and Spain, all of which seem to have enjoyed booms in the stock and property markets over the past 10 years. The problems lie in South Korea’s heavy reliance on exports. If the U.S., a major export market for South Korea, were to falter, causing China, whose economy is dependant on the U.S., to falter in turn, the situation would worsen significantly. Isn’t it true that South Korea posted a trade surplus by exporting machines and semi-finished goods to China? Most importantly, international financial markets are in turmoil, which makes me think that the global economy will continue to suffer for at least a year,” Chang said. “The economic fundamentals have weakened (since the Asian financial crisis), so Koreans must get it into their heads that U.S.-style capitalism is not good. I’m worried because Korea seems to be leaning towards this model.”

Please direct questions or comments to [englishhani@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 3[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 4After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 5[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 6Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 7US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 8All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 9[Photo] Smile ambassador, you’re on camera

- 10[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda