hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Traces of forced mobilization-part six] Temple death registries in Japan evidence of conscripted labor

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the forceful annexation of Korea by Japan in 1910. A number of issues, however, remain unresolved between South Korea and Japan. This is part six of the Hankyoreh‘s series about traces of history, which has been made in hopes that both countries are able to move together toward a brighter future after having resolved remaining issues concerning conscripted labor and other human rights issues.

Iizuka is the central city of the Chikuho region on the Japanese island of Kyushu. For decades from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, it prospered as a mining city, and it is home to the stately mansion of the Aso family. This structure may be seen as a glimpse into the time when three to four generations of former prime minister Aso Taro’s ancestors reigned as lords of the region, using the money they earned from mining development to expand their work into railroads, cement, banks and hospitals. The mansion was nearly burned down once by angry Korean workers.

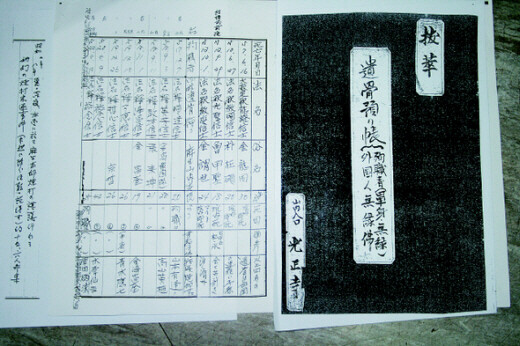

The record of the workers’ arson plot against the Aso mansion lies not in a document from the Tokko, police officers that dealt with political offenders during the Japanese Empire, or from one of the Aso businesses, but in a temple document. At the entrance to the Sannai Mine, one of seven managed by the Aso family in the Chikuho area, is the Goshoji Temple. The reference to the arson plan was included in a Goshoji human remains interment document obtained by the Hankyoreh. It says, “Summer of Showa Year 7 (1932), conspiracy to commit arson against Aso residence was committed at night at the main temple.” This is followed by the words, “Arson uncompleted, around 15 to 16 individuals took part, head monk attempted to dissuade them beforehand.”

Did the arson plot really happen? The document’s writer was Fujioka Seijun, then the head monk. His record seems to fit the circumstances at the time. An economic depression had continued in the wake of the crash of the New York Stock Exchange in 1929, and the cold winds hit the mines of Chikuho as well. Having previously withstood the conglomerate mining companies through low wages and subcontracting, the Aso family began closing some of its shafts and dismissing workers, starting with the elderly and Koreans. As the interests of the Japan Coal Miners’ Union, which was attempting to organize Korean workers, coincided with those of Korean miners who wanted improved treatment, a general strike took place in the Iizuka area in August 1932. Police, youth associations and officials in charge of Korean labor used violence to brutally repress the strike, but the Korean workers scattered to shrines and temples, where they continued the struggle for another three weeks.

The interment form included a long list of people who died in accidents at the mines and had no surviving family. They are listed according to the format of date of death, followed by legal name, real name, age, cause of death, and additional comments. The names of Koreans jump out on the list of victims. There are also cases where a Japanese name is written alongside, or where only a Japanese name is recorded. The ages range from the teens to the forties. Many causes of death are listed as ‘instantaneous death within the shaft’ or ‘died while on duty.’ The implication of ‘died while on duty’ is scarcely different from accidental death.

Noh Gap-seong, who died at the age of eighteen in a mining accident on Sept. 29, 1939, is the youngest person on the list, apart from some small children. A note next to his entry reads ‘eve of marriage.’ This seems to reflect the troubled emotions of Hujioka about the Korean bachelor from Baekgu Township in Gimje County in Korea, who suffered a tragic death just a day before his wedding. The real name of another Korean, who had been entered on the interment form only by his Japanese name and was affiliated with the Hokoku Tai labor corps, was uncovered through the efforts of Japanese civic groups and the Truth Commission on Forced Mobilization Under the Japanese Imperialism. According to an investigation of newspaper reports and cremation approval forms, twenty-eight-year-old Choi Yeong-sik was born in Seosan, South Chungcheong Province, and met his tragic death on Sept. 3, 1943, while attempting to rescue a Japanese miner trapped by a cave-in.

The interment form contains numerous pieces of such information. Another temple document with more detailed information is the death register. This register, installed in every Japanese temple since the early 17th century, basically contains the Buddhist name, real name, date of death and age at death of the deceased. Depending on the temple, information such as cause of death, status, and lifetime activities may also be included, and there are also family records spanning several generations. In modern terms, it could be called a database of personal information. The reason death registers have such significance for determining the circumstances of conscription and verifying the deceased is because the Japanese government and businesses destroyed or concealed related documents in the immediate wake of the nation’s defeat. Some overseas Korean researchers in Japan like Kim Gwang-yeol have been traveling around the temples of Chikuho for decades asking the head monks to allow them to read the death registers. The painstakingly collected details have been published in a number of research papers.

Currently, however, reading the death registers is prohibited as a rule. The justification given for the strict prohibition is the protection of private lives, in light of Japanese discrimination against burakumin. This term is used to refer to the lowest class of the population, which was previously also called hinin, meaning ‘non-human.’ Reportedly, there were many instances in the past in which private detective agencies were commissioned to examine death registers in order to check family histories for new employees or prospective marriage partners.

The understanding of the relationship between the remains of Korean workers and the reading of death registers varies widely between orders and temples in Japan. Bridging that gap will require restoring communication and trust between Buddhist groups in both countries, but the reality is a different story. Experts unanimously state that there is not enough expression of interest at the order level or systematic activity, as interested monks in Korea generally pursue separate contacts.

Please direct questions or comments to [englishhani@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 2AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 3South Korea officially an aged society just 17 years after becoming aging society

- 4Noting shared ‘values,’ Korea hints at passport-free travel with Japan

- 51 in 5 unwed Korean women want child-free life, study shows

- 6Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 7Why Kim Jong-un is scrapping the term ‘Day of the Sun’ and toning down fanfare for predecessors

- 8Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 9[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 10Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government