hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Refugees to South Korea languish in stateless limbo

By Um Ji-won, staff reporter

Once again, he is worried about where he’ll sleep. He is basically homeless. He can’t stay at his friend’s house anymore after drawing suspicion from the landlord. All he has in his pockets is a few thousand won (1,000 won = US$0.87). He came from thousands of kilometers away to stay alive, but now 39-year-old Mirembe finds his life in constant jeopardy.

He doesn’t regret crossing the Indian Ocean to survive. In his homeland of Uganda, a protracted civil war has been raging since 1986. People he knew mistakenly believed he had joined the rebel army. His wife disappeared without a trace just before he fled the country in February 2006. Mirembe believes someone killed her. “If I hadn’t left that day, I would have been next,” he said, tears welling in the corner of his eyes.

Mirembe received a student visa that year and hurriedly made his way to South Korea, a country he had heard about from missionaries. His aim in applying for refugee status was basic protection. But there was something he didn’t realize: the government still conducts a refugee status eligibility review that takes three years.

The first two years were tolerable. Applicants for refugee status receive a G-1 “humanitarian sojourn” visa while awaiting a final result. Mirembe didn’t receive much help from the government, but he did have a minimal level of status guaranteed, which allowed him to make enough to stay at a flophouse while working part-time at an automobile factory. When work was unavailable, he stayed at a shelter operated by an NGO that helps migrant workers.

But his visa elapsed when his refugee status was denied in 2009. The reason given was that he was “not in a political position to feel his life was threatened in his homeland.” Since then, he has been traveling around from day to day looking for a place to rest, his only belongings carried in a small gym bag. Factory owners don’t give work to refugees without visas.

Mirembe depends on the kindness of friends. If he gets his hands on some pocket money, he asks to bunk at an internet cafe. Some days, even this doesn’t work out. He can’t count the number of times he has had to sleep at a park or on the street.

Mirembe is now in his third year of being stateless. In late 2011, an administrative suit he had filed against the Justice Ministry’s decision to deny him refugee status was dismissed. In the very country he came to in the hopes of seeing his life and livelihood protected, he is adrift with nowhere to go. The passport issued to him by the Ugandan government has expired, so he can’t take refuge in another country. His only option is to stay here illegally.

The one route available to him is to have the Ugandan embassy in South Korea issue a travel certificate so he can return home. But that would mean near certain death.

“If I go back to Uganda, I could only survive by joining a rebel army,” he said, the desperation evident in his eyes. His only way to make enough to live is to carry a gun for the rebels, but either way his life is in jeopardy.

The Center for Refugees’ Rights (NANCEN) estimates that there are more than 700 people like Mirembe living with expired passports that leave them unable to go anywhere. Much of the blame for this lies with the excessively long refugee status eligibility review period. Applicants who are denied refugee status after waiting years for the result end up losing the opportunity to go elsewhere because their passports expire while they wait. A Justice Ministry review takes eighteen months to two years. It can take more than five years if an administrative lawsuit is filed to appeal the decision.

A ministry official said the long review period stemmed from being short-staffed.

“We have just eight employees in charge of refugee reviews, but we can’t just add new people because there isn’t a social consensus on the treatment of refugees,” the official explained.

Very rarely are applicants deemed eligible. NANCEN secretary-general Kim Seong-in said the rate of approvals in South Korea was “absurdly low by international standards, and the eligibility criteria are vague.”

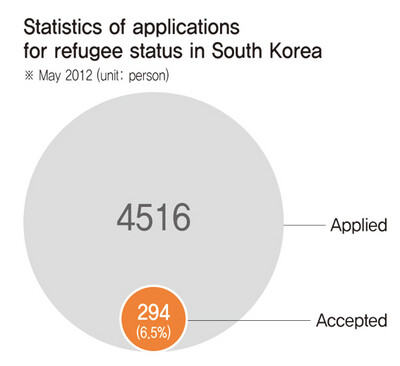

According to annual Justice Department figures for refugees, only 294 of the 4,516 applicants since South Korea joined the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees in 1992 was approved as of May 30, 2012, roughly six percent. This is far below the average of just over 30% for most developed countries. In terms of refugees as a percentage of the population, South Korea’s rate of 0.0005% is below Hungary (0.06%) and Mexico (0.0011%), to say nothing of Germany (0.72%) or the United Kingdom (0.43%).

The late 2011 enactment of the Act on the Status and Treatment of Refugees marked something of a step forward, but it has yet to go into effect.

Kim Seong-in said, “We have a legal basis now for supporting refugees, but the Justice Ministry hasn’t talked about follow-up measures, so applicants are still going without the livelihood foundation that would allow them to enjoy even minimal human rights.”

[Mirembe’s name has been changed for this article in order to protect his identity.]

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 2Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 3N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 4[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 5Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 6Kim Jong-un expressed ‘satisfaction’ with nuclear counterstrike drill directed at South

- 7[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 8[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 9[Cine feature] A new shift in the Korean film investment and distribution market

- 10[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady