hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

US and Japan agree to upgrade military alliance

By Gil Yun-hyung, Tokyo correspondent and Park Hyun, Washington correspondent

Since Japan’s surrender in World War II in 1945, there have been two major changes in its relationship with the US.

The first took place at the summit between US President Ronald Reagan and Japanese Prime Minister Zenko Suzuki in May 1981. During this meeting, the relationship between the two countries was described for the first time as an “alliance,” signifying military cooperation. Japan agreed to the US request to field P-3C anti-submarine patrol planes and took on the task of watching for Russian subs.

The second change was the revision of the Guidelines for Japan-US Defense Cooperation in 1997. The US asked Japan to be prepared to respond to regional situations such as the nuclear threat posed by North Korea. The guidelines were first compiled in 1978 during the Cold War over concern about invasion by the Soviet Union. When the guidelines were revised in 1997, the main focus was a possible military conflict on the Korean peninsula.

In May 1999, Japan enacted a law regarding situations in the area around Japan, and the scope of the activity of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces was expanded from Japanese territory to encompass the surrounding area.

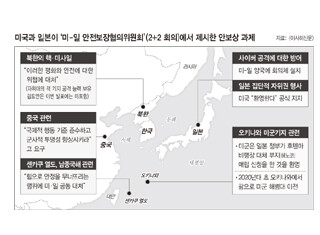

The joint statement that was issued on Oct. 3 after the Japan-US Security Consultative Committee Meeting (commonly referred to as 2+2) between the foreign and defense ministers of the two countries can be seen as the third shift in the two countries’ relationship.

One aspect which is different from the past is that this time it was Japan requesting a change. Japan was seeking to draw upon American power to counter China in the Senkaku Islands (called the Diaoyu Islands in China) and to achieve the right to collective self-defense, something that Japanese conservatives have long coveted.

Hobbled by its fiscal deficit and troubles in the Middle East, the US appears to have accepted these demands to some degree and called on Japan to take on a greater military role.

If the Japanese Self-Defense Forces gain the ability to engage in collective self-defense, it will mean that Japan has effectively scrapped the exclusively defense oriented policy that it has maintained for the past sixty years, focusing strictly on defense and explicitly stating it will not initiate hostilities.

In the joint statement, the two countries “decided upon several steps to upgrade significantly the capability of the U.S.-Japan Alliance” and mentioned “revising the 1997 Guidelines for U.S.-Japan Defense Cooperation, expanding security and defense cooperation in the Asia-Pacific region and beyond.”

The US endorsed the policies pursued by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe such as “exercising its right of collective self-defense, expanding its defense budget, reviewing its National Defense Program Guidelines, strengthening its capability to defend its sovereign territory, and broadening regional contributions, including capacity-building efforts vis-a-vis Southeast Asian countries.”

In effect, the US granted Japan its request for collective self-defense, with the proviso that Japan monitor and curb Chinese maritime expansion by working with Asian countries like the Philippines and Vietnam that are engaged in territorial conflicts with China.

By placing the Global Hawk, an advanced unmanned reconnaissance aircraft, and the P-8, the latest anti-submarine patrol plane, in Japan, the US signaled its intention to keep an eye on China.

These are the conflicting motivations underlying Japan and the US’s superficial consensus on the issue of collective self-defense.

The Japanese media also drew attention to the subtle contradictions between the US and Japan.

“Japanese Defense Minister Itsunori Onodera referred to the tensions between Japan and China each time that he spoke, while US Secretary of State John Kerry and Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel avoided mentioning this,” the Asahi Shimbun reported on Oct. 4.

Other papers also made similar observations, referring to “a difference of opinion on the Senkaku Islands” (Mainichi Shimbun) and suggesting that “the US and Japan are not on the same page in their policy toward China” (Tokyo Shimbun).

These papers observed that there is a considerable gap between the American and Japanese responses to the dispute over the Senkaku Islands.

China lashed out angrily, and South Korea did not conceal its concern.

China’s state-run Xinhua News Agency ran strident criticism of the statement on Oct. 3. Japan and the US have failed to get rid of their Cold War mentality, Xinhua said, arguing that the two countries are increasing tensions and threatening the peace and stability of the Asia-Pacific region by strengthening their military alliance.

The South Korean government did not offer an official response. Instead, an official in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs came forward to say on condition of anonymity that there are no changes in South Korea’s existing position that collective self-defense should be developed in a transparent way so as to assuage the concerns of neighboring countries and to contribute to the peace and stability of the region.

In the US, the New York Times expressed its support for the US move to strengthen Japan’s military capability in a bid to counter China. However, the paper noted that this would not be an easy task given likely opposition from other countries in the region.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/8317138574257878.jpg) [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father![[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms? [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/3617138579390322.jpg) [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 2Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 3Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan

- 4[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 5Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 6Opposition calls Yoon’s chief of staff appointment a ‘slap in the face’

- 7[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 8[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 9New AI-based translation tools make their way into everyday life in Korea

- 10Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76