hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Every Sunday, foreign migrant workers get free medical care in Gwangju

By Jung Dae-ha, Gwangju correspondent

Samson Pale, a 27-year-old from the Philippines, arrived at the medical office of the Gwangju Migrant Workers’ Clinic Center (GMWCC) in Gwangju on the afternoon of Dec. 1. Speaking in broken Korean, he said his throat hurt. A worker at a molding factory in Gwangju’s Hanam Industrial Complex, he had been coughing up phlegm for the past three days. A friend had told him about the center.

Yun U-ram, a 36-year-old family practitioner volunteering there, examined him with a stethoscope and wrote out a prescription. “Please don’t smoke,” Yun implored. Pale left the doctor’s office and headed over to the area next to the main desk where pharmacist Song Mi-kyung, 50, was filling prescriptions. He handed the prescription over and received the medicine.

“I didn’t have time to go to the hospital during the week because I was working,” said Pale, who has been in South Korea for less than two years. “I’m grateful for the free treatment.”

The GMWCC runs a free clinic every Sunday from 1 to 5 pm. When a Hankyoreh reporter stopped by, it was crowded with around 60 people - migrant workers, female marriage migrants awaiting citizenship and their children. Three kinds of treatment were available: general medical care, Oriental medicine, and dental care. Yu Kyung-nam, a 33-year-old social worker who volunteers as general manager for the center, was checking patients in. The migrant workers coming in were asked if it was their first visit; if they nodded, Yu handed them an information sheet and asked them to fill it in. Ri Yong-su, a 61-year-old ethnic Korean from China and regular visitor to the center, was on hand to provide interpretation for Chinese patients who did not speak Korean. Patients who had been there before took their records out from a case across from the desk and handed them to Yu.

After they finished checking in, their blood pressure was tested by An Bo-bae, 23, and Jo Ye-bin, 21, two nursing student volunteers from Chonnam National University.

Most of the center’s patients are migrant workers from small assembly, injection, molding, or construction companies at Hanam or the Gwangju High-Tech Industrial Park, or in other South Jeolla Province communities like Naju, Jangseong, and Hwasun. Other frequent visitors include marriage migrant relatives who don’t have health insurance.

“Most of the time, we see workers in difficult, physically hard jobs who complain about musculoskeletal problems,” said Kim Kyung-hwan, a 53-year-old doctor of Oriental medicine at the Nampyeong Jangsu Oriental Medicine Clinic in Naju.

At the dental clinic, a dentist with the Dentists’ Association for Healthy Society (DAHS) was treating patients with five to six volunteer assistants. Since the center does not have a full range of examination equipment, patients with particularly serious conditions are directed to undergo closer examination at cooperating facilities. Pisil, a 47-year-old worker from Cambodia, was visibly worried after receiving instructions to get a closer examination at the clinic of Lee Yong-bin, the 47-year-old family practitioner who is head of the center.

The GMWCC opened eight years ago, in June 2005. Its original location in Gwangju’s Gwangsan district was chosen because of the large number of migrants living and working there. The center occupied a small rented space in the Sanjeong neighborhood. But migrant workers at small factories in Hanam and the Pyeongdong Industrial Complex had trouble using the facilities. At the time, a number of organizations - the Gwangju Migrant Workers’ Center, the Gwangju Migrant Workers’ Missionary Association, and the Gwangju Migrant Workers‘ Cultural Center - teamed up with a volunteer group from Kwangju Christian Hospital and doctors from missionary groups to offer free treatment for migrant workers on Sunday afternoons.

“The workers had to work day and night on weekdays, and even holidays, so they never had time to come to the hospital,” recalled Seok Chang-won, a 53-year-old pastor with the Gwangju Migrant Workers’ Missionary Association. “Some of them just put up with the pain because they knew the factory machinery would have to be idled while they went to the hospital. So we decided that Sunday afternoon was the best time for them to get treatment.”

Soon, the Gwangju/South Jeolla chapter of DAHS began showing interest in the free treatment program for migrant workers. In winter 2004, Lee Geum-ho, the 40-year-old director of the chapter’s treatment project department, went to see Lee Cheol-u, a 62-year-old pastor at Moodeung Church and member of the Gwangju Migrant Workers’ Center, and told him that members wanted to provide free treatment to migrant workers.

“Reverend Lee suggested meeting with three volunteer groups for migrant workers to discuss developing a system for treatment,” Lee Geum-ho recalled.

As it happened, Lee Yong-bin was also looking for ways to provide free treatment. A veteran of the student movement who had been vice president of the Chonnam National University student council in 1987, Lee had asked Gwangju Migrant Workers’ Cultural Center director Lee Cheon-yeong if there was any way of helping the workers. Soon, doctors of Oriental medicine were joining in, including clinic director Choi Hee-seop. Since they were putting something together already, they decided to combine different fields into a full-fledged treatment center. After some discussion, they developed a volunteer program where 30 dentists, 30 regular physicians, and 10 doctors of Oriental medicine could come out about one Sunday every two months.

“At first, we were worried there wouldn’t be any patients,” recalled Lee Yong-bin. “But after about six months went by, enough word of mouth had gotten around that we were getting a lot of them.”

The organizing principle of the center is the “beginner’s mind” and a volunteer’s sense of dedication. Around 150 volunteers work there, from fields like regular and Oriental medicine, dentistry, nursing, pharmacology, administration, interpretation, and counseling. Recently, more and more volunteers have been participating from middle and high schools. In July 2008, the center relocated to its current site in Usan. Last year saw 1,421 regular medical visits, 942 Oriental medicine visits, and 836 dental clinic visits. A total of 3,199 treatments were provided for roughly 2,700 patients, with 1,657 prescriptions for free medicine dispensed. Around 20,000 visits have taken place since the center opened in 2005.

Nearby Hanam Seongsim Hospital helps out with blood testing, while Lee Yong-bin‘s family medicine clinic provides free examinations with ultrasound and X-rays. Other partner facilities include the Choi Se-mi Ob/Gyn Clinic, the Best Otorhinolaryngology Clinic, Balgeun Ophthalmology 21, Donga Hospital, Gwangju Saeuri Hospital, Kwangju Christian Hospital, and Cheomdan Medical Center, which provide free examinations, treatment, and operations.

Lee Seung-nam, the center’s 44-year-old secretary-general, recalled one case from two years ago.

“There was a migrant worker who was in very bad shape, and we asked Cheomdan Medical Center to do an examination,” Lee recalled. “It turned out to be the early stages of liver cancer. The patient was operated on at Chonnam National University Hospital (CNUH) and ended up recovering.”

Once a month, CNUH offers free blood, urine, X-ray, and ultrasound examinations for migrant workers referred by the center. The university’s nursing college also helps with examinations, counseling, and statistics. Free dental prosthetics and other support are offered by dental supply companies like Cham, Vision, and Daemyeong.

Running the center costs about 35 million won (US$33,200) a year. Roughly 20 million won (US$19,000) of that comes from monthly payments of 50,000-100,000 won (US$47-95) from 50 or so members of DAHS, the Korean Association of Family Medicine, and the Association of Korean Medicine.

The city of Gwangju and the district of Gwangsan provide 13.5 million won (US$12,800) and 1.5 million won (US$1,400) a year, respectively, for medicine purchases.

Many are looking at the GMWCC to develop in the future into a one-stop center offering systematic support for migrant workers and marriage migrants. “There are still a lot of the same healthcare blind spots for migrant workers,” said Seok Chang-won. “Foreigners who don’t get health insurance benefits can‘t afford the costs if they get pregnant or seriously ill.”

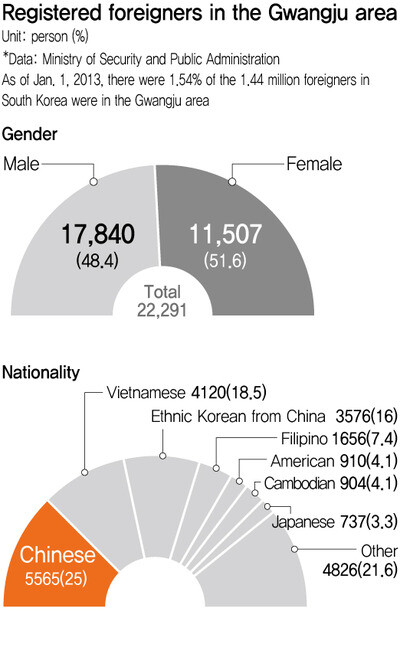

At the moment, twelve different migrant worker and marriage migrant groups in the Gwangju area are calling for the establishment of a general migrants’ or migrant workers’ support center that would be equipped to address medical, cultural, and educational needs. The city is home to 22,291 international residents, including marriage migrants, exchange students, and around 6,400 foreign workers.

“What we really need is warmth,” said Lee Cheol-u, who heads the preparatory committee for the support center’s construction. “We need to look at migrant workers as members of our social community.”

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 3Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 4Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 5The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan

- 6Korea protests Japanese PM’s offering at war-linked Yasukuni Shrine

- 7[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 8‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 9“Korea is so screwed!”: The statistic making foreign scholars’ heads spin

- 10[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?