hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Reportage] Koreans on Sakhalin watch the days tick by on their new calendars

By Kim Min-kyoung, staff reporter in Sakhalin

How can getting a simple calendar be enough to drive elderly women to laughter and tears? Calendars are easy enough to pick up for anyone visiting South Korea, but these women have difficulty even moving around. Look online? They don’t even have computers at home. The print on the desktop calendars that South Korean companies typically make is too small for them to read. Perhaps most importantly, few people even knew just how much a lunar calendar means to first-generation Korean immigrants on Sakhalin Island.

“Khorosho, khorosho.”

The elderly women’s laughter rang out on Jan. 17 in the office of the Korean association in Uglegorsk, a port town in Russia’s Sakhalin Island. “Khorosho” means “great” in Russian.

“Oh, my. Thank you.”

“And you brought a thousand of them! It must have been such trouble.”

Their faces lit up as they spread out the lunar calendars. One of the beaming women was 84-year-old Yeom Chang-wol. She looked over each page before her eyes fixated on April. The background image for that page was a picturesque photo of Gwanghallu, a pavilion in Namwon, North Jeolla Province.

“It’s beautiful,” she said. “I’d love to go sometime.”

Yeom was born in Hamhung, a city in South Hamgyong Province in what is now North Korea. She came to Uglegorsk with her mother, who had come to find her husband after he had been forcibly drafted to work in the Sakhalin coalmines. No one lived on the island, which was originally Russian territory. Japan acquired the southern part (below the 50th parallel) after its 1905 victory in the Russo-Japanese War. Renamed “Karafuto,” the resource-rich region became the focus of active development efforts after the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, with Japan delving into the area’s stores of coal and timber. Koreans were drafted to do the work. No precise information is available on the number of conscriptees, but a total of 43,000 Koreans were reported in South Sakhalin after Liberation Day on Aug. 15, 1945 (following Japan‘s World War II surrender).

Yeom’s family members all returned to North Korea in 1956. She stayed behind on Sakhalin with her husband. During the Japanese occupation, she was renamed “Fuko Yoshida”; when the Soviet Union retook sovereignty over the island, she became “Nina.” Seemingly the only thing that didn’t change was her birthday according to the lunar calendar. That date became central to her roots and her identity.

“My birthday is the first of the eleventh month by the lunar calendar,” she said. “Our children don’t know about the lunar calendar, so they wish me a happy birthday on November 1 by the solar calendar. They don’t have calendars like this either. But we do everything by the lunar calendar. We’re Koreans, not Russians. We want to do things by the lunar calendar.”

Grinning, Yeom said the calendars were the greatest gift for the Lunar New Year.

Unlike Yeom, 80-year-old Kim In-sun doesn’t know her birthday. “When I was eleven years old, my mother went home because my older brother was sick, and that’s the last I ever heard from her,” she said. “Fathers back then never remembered their children’s birthdays. I just always thought my birthdays were the days when I had something good to eat.”

Unable to return to Sakhalin from her hometown of Cheongdo in North Gyeongsang Province, Kim’s mother longed to see her husband and daughters again. In 1946, she died with a broken heart. Left alone, her father never remarried. He hoped that he might return home someday soon.

Korea was “liberated” on Aug. 15, 1945, but liberation never came to Sakhalin. Japan worked to repatriate its own citizens there, but did nothing for the Koreans, who were no longer Japanese citizens. The Soviet Union, desperate to recover from the ravages of war, did not want the Koreans to leave Sakhalin. Most of those who were drafted to work there had come from the South, but the government there, facing its own problems of division and war, did nothing for them. Instead of liberation, it was a time of painful separation. The Sakhalin Koreans were twice abandoned - once by colonization, again by division and the Cold War.

Kim In-sun doesn’t know where her birthday falls on the lunar calendar, but that doesn’t mean she has no use for one. “I look at the calendar when I‘m farming,” she explained. “I sow cabbage on the first dog day, and I sow radishes on the second. In the past, everyone had their own field.”

Kim married her husband, a former draftee to the Bikov coal mine, in 1950. Together, the two worked the land diligently once it began to thaw. After Liberation, they had no nationality and didn’t speak Russian. They had trouble finding work, and earned less than the ethnic Russians when they did. Farming was essential to put food on the table and pick up some extra money from sales. Kim recalled looking for a lunar calendar while visiting a city near the ocean in order to see the tide times. The first and 15th of every month on it have the biggest tidal differences. When the water receded, she went out to collect clams and shrimp. The lunar calendar was crucial to their survival.

A thousand copies, specially made by 1,600 donations

“Calendars? It was so frustrating every time I came here. I was thinking, ‘Where am I going to get all of them? And how am I supposed to get them here?’”

Lee Eun-young, a 36-year-old activist with Korean International Network (KIN), has been visiting Sakhalin every year since 2006. KIN does work on behalf of Koreans in Sakhalin Island, and Lee found herself entertaining an “odd” request every time she visited in January ahead of the Lunar New Year. They wanted Korean calendars.

In South Korea, the calendars are so widely available that anyone ordering delivery food in December is likely to get one. On Sakhalin Island, they’re a rare prize. And for the first-generation Koreans there - people who follow the lunar calendar for birthdays, ancestral rites, and major holidays - they are essential.

Lunar calendars were tough to find in Russia, which uses only the solar calendar. First-generation Sakhalin Koreans make their own kimchi, soy sauce, and fermented soybean paste in Russia, but they didn’t have the means to make lunar calendars. Today, around 1,000 first-generation Koreans live on the island - people who were born or lived there before Liberation Day in 1945. Even if every household had calendars to spare, gathering up 1,000 of them was a tall order.

“Last year, we brought 300 calendars made by the Overseas Korean Foundation, and it wasn’t nearly enough,” recalled Choi Sang-ku, a 41-year-old KIN volunteer. “We had only so many calendars, and everywhere we went the elderly Koreans asked for ‘just one more.’ We felt kind of helpless.”

Eun-young and Sang-ku finally found a way to beat the calendar troubles. They decided to design a calendar that would be customized for the needs of Koreans living on Sakhalin Island. While their initial goal was showing the dates of the lunar calendar, they could not just ignore Russian holidays.

In the end, they settled on combining the Russian solar calendar and the Korean lunar calendar. They also resolved to print the numbers in a large font for elderly Koreans. Another idea was including photos that captured the beauty of the homeland for their overseas compatriots who had longed for home their entire lives.

The biggest difficulty was money. Making the calendars and shipping them both cost money, and they needed 10 million won (US$9,230). The photos were donated by photographer Lim Jae-cheon. He took shots of Korea’s most iconic spots, including Kwanghan Pavilion in Namwon, Sancheong County in South Gyeongsang Province, and Hahoe Village in Andong.

The group also started raising money using Naver “happy bean” in the second half of 2013. But in November, the money they had raised fell fall short of their budget. They found themselves with a tough choice to make.

“The money we had raised to that point wasn’t enough to make the calendar. But we came to the conclusion that we had to keep the promise we had made to the first-generation Sakhalin Koreans and to the people who had donated money,” said Sang-ku.

Fortunately, donations kept coming in. Thanks to donations from 1,600 people and the support of the Overseas Korean Foundation, they were able to print 1,000 copies of this truly unique calendar. When the two boarded the plane to Sakhalin on Jan. 14 to deliver the special present, their hearts were filled with excitement.

On Jan. 20, Eun-young and Sang-ku visited the Center for Elderly Koreans in Yuzhno-Sakhalinsk. Having heard that guests from Seoul were bringing calendars, more than 20 elderly women were gathered at the center despite the temperature, which was hovering around 20 degrees below zero. These were women who had made it through the heartache of Korea’s contemporary history - the Japanese colonization, the division of the peninsula, and the Cold War.

A big grin lit up the face of Lee Bok-sun, 78, as she looked at the calendar. She smiled first when she saw the calendar, and again when she saw the people from Seoul. “I was just counting down the days till my death, and then this calendar arrived. I thought that we had been forgotten because we are here in Sakhalin. It is so great to see this calendar, because it seems like we are being remembered. I bragged to other people that the calendar came from Korea,” she said.

Lee Bok-sun, who was born in the Sakhalin town of Uglegorsk in 1936, had never had a chance to live in Korea, but she is well-versed in the lunar calendar.

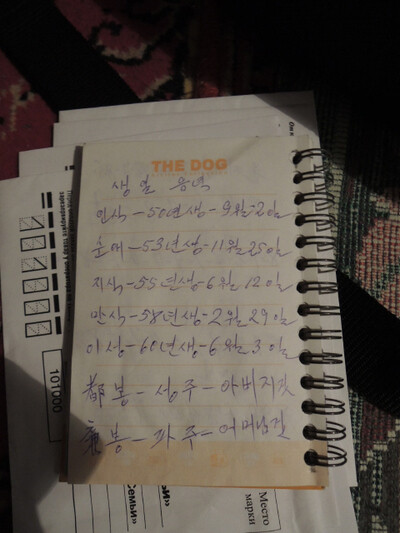

“Let’s take a look here. This January, the lucky days are the 9th, 10th, 19th, 20th, 29th, and 30th. These are days when it is okay to do repairs on your house or to move to a new one,” said she, using the North Korean accent. The first generation of Sakhalin Koreans received their schooling from North Korean teachers at the Joseon (Korean) School.

“Since I always pay attention to things like this, my children always ask me things like when a good day would be for a housewarming party,” Bok-sun said.

Her parents taught her how to read the lunar calendar. They were illiterate in both Korean and Japanese. She had to learn Japanese, Korean, and Russia not at home but at school.

But reading the lunar calendar was not something that was taught at school, so she learned that from her parents. The lunar calendar served as a bridge connecting her with her homeland.

“The Russian calendar is boring, but the Korean calendar has all kinds of things: the Lunar New Year, Chuseok [the Harvest Festival], Children’s Day, Parents’ Day, and Daehan, Sohan, Gyeonchip, and Usu [four seasonal days on the lunar calendar]. I like seeing Korean holidays. Oh, this is just great!” The person speaking was Seo Yun-geum, 80, who was looking at the calendar along with Lee Bok-sun.

She likes listening to Korean songs, and her favorite song is “My Homeland Seen in My Dream.” She only reckons her birthday by the solar calendar now, but she was delighted with the Korean calendar. Anything with the word “homeland” in it is fine by her, she said. The calendar represented her longing for homeland.

The calendar was not the only present that Lee Bok-sun is waiting for. “I got Russian citizenship in 1978 because I was cold and hungry and wanted to make a living,” she said. “I want South Korean citizenship, so why won’t they give it to me? They say that I can’t get any compensation because I don’t have that. The reason I haven’t gone to Korea is because I don’t want to be separated from my children, and they don’t give me a penny because I am staying here. . .”

Standing beside her, Seo Yun-geum spoke up. “The Japanese look down on us, saying we smell like kimchi. The Russians despise us for leeching off them and ask us why we don’t go home. I have cried many times with sorrow, and now it seems Koreans are looking down on us as well,” the old woman said.

The first generation of Koreans who have been on Sakhalin Island since before August 15th, 1945 - the day Korea was liberated from Japan - can go to Korea at any time, thanks to the repatriation program run by the South Korean and Japanese governments since 1997. Thus far, around 4,000 first-generation Koreans have returned to Korea, while 1,000 have elected to remain on the cold land of Sakhalin instead of their homeland.

They have done so because of their children. Currently, the repatriation program is limited to first-generation Koreans, their spouses, and up to one child with a disability. Faced with the cruel choice of their homeland or their families, Lee Bok-sun and Seo Yun-geum opted for the latter.

In Nov. 2012, Democratic Party lawmaker Jeon Hae-cheol proposed special legislation to help Koreans in Sakhalin. The bill would expand the scope of the repatriation program to one child and their spouse and provide aid to the Koreans remaining on the island. This was the third attempt since 2004.

The goal is to pass the bill in a special session of the National Assembly next month, but lawmakers are lukewarm on the issue. The relevant government ministries are also opposed to the legislation, pointing to issues including extra work, equality with other Koreans overseas, and how it might hamper relations with Russia.

“We couldn’t pass a single law, and all we brought is this one calendar. To think that they would say ‘good job, thanks, see you next year’ because of that one calendar. . .” Eun-young’s voice trailed off, and her eyes filled with tears.

It took a significant amount of time to make the calendar that is customized for first-generation Koreans living on Sakhalin Island. While they at last had produced enough - 1,000 copies - they were still unable to give an extra one to all of the older men and women who wanted one.

But the real problem is not the number of calendars but rather the number of people who are supposed to receive them. There is not much time left for the first generation of Sakhalin Koreans, who are now more than 69 years old. When it comes to much more than calendars, they can’t wait much longer.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0415/7517131654952438.jpg) [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

[Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics![[Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0412/1017129080945463.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

[Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

- [Guest essay] At only 26, I’ve seen 4 wars in my home of Gaza

- [Column] Syngman Rhee’s bloody legacy in Jeju

- [Editorial] Yoon addresses nation, but not problems that plague it

- [Column] Can Yoon and Han stomach humble pie?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- 2[News analysis] Watershed augmentation of US-Japan alliance to put Korea’s diplomacy to the test

- 3[Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- 4[Photo] Cho Kuk and company march on prosecutors’ office for probe into first lady

- 5[Column] A third war mustn’t be allowed

- 6‘National emergency’: Why Korean voters handed 192 seats to opposition parties

- 7Exchange rate, oil prices, inflation: Can Korea overcome an economic triple whammy?

- 8After Iran’s attack, can the US stop Israel from starting a regional war?

- 9[Editorial] New KBS chief is racing to deliver Yoon a pro-administration network

- 10[Editorial] S. Korea should take a note from US-China tactical compromise