hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special report- Part I] S. Korean companies’ shameful self-portrait in Southeast Asia

By Hwang Ye-rang, Hankyoreh 21 staff reporter

Gunshots have rung out once again on continental South Asia, this time in Chittagong, a port city in the south of Bangladesh. As the police suddenly opened fire, the 5,000 workers demonstrating in front of a Youngone shoemaking plant in the Korean Export Processing Zone (KEPZ) quickly scattered. One of them, a 20-year-old woman, was hit. She was taken to the hospital, where her heart stopped. The bloodbath came amid the workers’ payday protests over how their stipends had been cut.

The events happened on Jan. 9. Six days earlier, five workers were fatally shot in Cambodia while calling for a hike in the monthly minimum wage. At US$66, the minimum wage in Bangladesh is even lower than the US$80 paid in Cambodia. In both cases, the victims were seamstresses. The clothes and shoes they sewed are sold all around the world under such well-known labels as The Gap and North Face.

On Jan. 9, crackling flames were blazing at the site where a Samsung Electronics cell phone factory is being built in the northern Vietnam province of Thai Nguyen. It all started when guards from a security service firm used a stun gun on a late-arriving worker who was trying to climb over the entrance gate. A crowd of 4,000 angry workers began throwing rocks, before setting fire to dozens of container boxes and motorcycles.

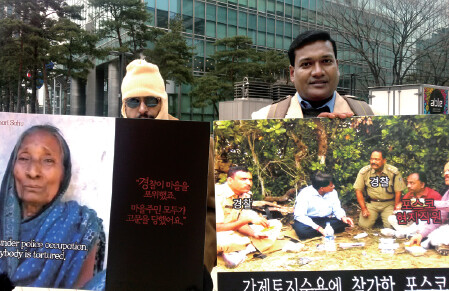

Another fire raged six days later on Jan. 15 - in India this time. Residents of the state of Orissa, opposed to steel plants currently being built there by POSCO, were burning effigies. In Patana, one of the sites, villagers set fire to figures representing President Park Geun-hye, Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, and Veerappa Moily, the Minister of Petroleum and Gas who granted POSCO a development permit. POSCO has had the project in the works since 2005, but ground has yet to be broken due to conflicts with 20,000 residents protesting their forced relocations and charges of environmental damage. Four residents have lost their lives in nine years of demonstrations. To villagers resisting having their homes taken away, the South Korean president - who demanded a solution to the “POSCO problem” during a meeting with the Indian Prime Minister - is nothing but an intruder.

It was the fourth incident in 2014, less than a month into the year. Yet another round of disturbing news involving a South Korean company overseas made its way home through local press reports and social media. The companies offered their own takes on the protests: Youngone claimed employees had “misunderstood the new wage system” and Samsung called the disturbance a “happening caused by an overzealous response by the security firm,” while POSCO fingered the Indian government as being responsible for the conflict with residents. It was hard to tell if they were explanations or excuses.

The queasy feeling is a familiar one. No sooner does one story about a South Korean company overseas being involved in human rights abuses die down than another one makes the news. Often the same companies are involved. The Bangladesh bloodbath was not the first at a Youngone plant in the country. In December 2010, three people lost their lives in a large-scale demonstration by workers disgruntled over their wages. Allegations were made at the time that local plant managers had beaten and detained workers who took part in the stoppage. Youngone, which produces items for the outdoor brand North Face under an OEM (original equipment manufacturer) arrangement, has 19 garment and shoemaking plants in Bangladesh alone.

The Vietnam protests ended in an unplanned clash, and in Brazil Samsung found itself in a less pliable position last year when it was called to court twice for worker exploitation. Labor prosecutors in Brazil filed suit to demand 250 million reais (US$104.2 million) from Samsung Electronics for “psychological damages.” Workers at a Manaus plant were suffering from musculoskeletal ailments traced to overwork - including standing for 10 hours a day without breaks and assembling cell phones at a rate of one every 32 seconds. It was the first time Samsung had ever been investigated by another country’s judicial body. In France, three NGOs filed suit claiming that customers were being defrauded by advertisements portraying Samsung as an “ethical” company. They had been disturbed by the findings of a 2012 study by the US group China Labor Watch, which found cases of children under 16 working at the plants of Samsung subcontractors in China. Samsung stated that its own investigations turned up no cases of minors being employed, but the controversy continued as additional allegations of child labor surfaced.

The number of cases of human rights infringements involving South Korean companies overseas, as reported by overseas news media and civic groups like Korean House for International Solidarity, amounts to well over 100 since 2000. Companies are obligated to respect human rights, at home and abroad. It is not a requirement by international law, but protections are demanded from companies by the multinational guidelines adopted by the OECD in 1976, as well as the ISO 26000 guidelines for social responsibility announced by the International Organization for Standardization and the UN’s Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. The idea of “responsibility” also includes an obligation not be “involved” in any human rights abuses. “Involvement,” according to a 2013 report commissioned by the National Human Right Commission of Korea (“Survey of Human Rights Abuses at South Korean Companies Overseas and Ideas for Improvements to the Legal System”), is understood as “cases where [a company] contributes to the occurrence of negative effects on human rights by another company with which it has a business relationship, or by the government of the host country.” By this definition, a company could not be considered “uninvolved” simply because it did not fire the guns or drive out residents itself. South Korean companies in Cambodia, Bangladesh, Vietnam, and India would all be potential accomplices.

A paycheck of less than ten dollars for 12 straight hours of work a day. Nasal passages permanently blackened by the dust settling on sections of fabric. Chronic pain from the stifling factory air. Is this the story of sewing workers in some third world country - perhaps Cambodia, or Bangladesh? They are actually from South Korea. It is the account of life as an apprentice at Seoul’s Cheonggye Market, circa 1975, as rendered in “Cheonggye, My Youth,” a meticulous chronicle of the history of the Cheonggye Garment Workers’ Union. Thanks to the union’s battle for higher wages, apprentice monthly salaries rose to 20,000 won in 1977 and 30,000 won in 1978. This South Korea of the 1970s is what comes to mind from recent reports of the situation faced by garment company workers in Southeast Asia: the long hours, the harsh working conditions, the unfair treatment of workers, the bottled-up rage of workers pushed past the breaking point - and the massive demonstrations that ensue.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

This article originally appeared at

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/8317138574257878.jpg) [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father![[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms? [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/3617138579390322.jpg) [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 2[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 3Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 4Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan

- 5Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76

- 6New AI-based translation tools make their way into everyday life in Korea

- 7[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 8Opposition calls Yoon’s chief of staff appointment a ‘slap in the face’

- 9[Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- 10Korean government’s compromise plan for medical reform swiftly rejected by doctors