hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Follow-up] While working like slaves, African performers live in squalor

By Bang Jun-ho, staff reporter

The hole in the glass front door was covered with silver paper and green tape. Willy, 30, who was living here with two coworkers from Zimbabwe, opened the door with some embarrassment. “As I said yesterday, we are living in a place like this. Koreans don’t typically live in houses like this, do they?” This reporter’s nose tingled with the smell of mold.

On the afternoon of Feb. 11, a Hankyoreh reporter visited the residence of African migrant workers who allegedly work in slave-like conditions at the Africa Museum of Original Art in Pocheon, Gyeonggi Province. I stepped into a room that museum director Park Sang-sun described as being “in somewhat decent shape,” but the room was so cold that I could see my breath, and it was full of mold.

The two-room house was the lodging place of Willy along with Lilmo, 28, and Eddie, 40, who came from Zimbabwe to South Korea to share their talent for sculpture. Eddie’s room is just over 3.3㎡ in size. With a bed taking up most of the room, there was barely space for a single person inside.

Willy stamped on the floor with his feet. “Cold, isn’t it? The heater doesn’t work in here,” he said. The next room where Willy and Lilmo sleep was bigger than Eddie’s room - about 10㎡ in size - but it also smelled of mold. Willy gestured at the wall, pointing to his nose to indicate the bad smell. It was hard to find anywhere without any mold.

A few African sculptures were scattered around the messy room. A washing machine and boiler took up most of the 6.6㎡ bathroom, meaning that tenants must squat to take a shower.

Throughout my visit, Willy was nervous. Someone was speaking in Korean outside. “Willy, you were in the paper yesterday, weren’t you?” the voice said.

Willy whispered, “That’s the village chief. He is on good terms with the museum. We’re staying inside because we figure the museum heard that a reporter came to talk to us.”

After a while, he pulled out an old English-language newspaper. My eyes were drawn to a one-page article with a big headline reading, “Africa in the Heart of Korea.”

“This is all fake,” [Willy said.] “The article says nothing but good things, even though the reality is like this. . .”

Trash was piled up along the walls of the other residence, which was described as even shabbier. That was the house of Faina, 27, from Zimbabwe. Faina is Willy’s younger sister. There was an opening in the ceiling of this house near the boiler, through which straw and dirt could be seen.

With Willy and the other two, we went to the museum. Faina, who had not been at home, was selling drinks and sculptures in the museum shop. “The work we do is always like this,” she complained. The dance performance is currently not taking place at the museum. Admission to the museum costs 7,000 won (US$6.54).

Following a report claiming that the African performers at the museum were working like slaves, not even being paid the legal minimum wage, museum management countered that they had provided the workers a monthly salary of 1.1 million won (US$1,027). But the bank slips that workers showed the Hankyoreh confirmed that they had gotten less than 600,000 won per month. There were even times when their monthly wages fell below 500,000 won, supposedly to cover their airfare.

“We provided the workers the four basic kinds of insurance, paid the rent for their accommodations, and covered the electricity bill. If you include all of those things, their salary reaches 1.1 million won,” Director Park said. This means that the museum deducted 400,000 won a month per person for sleeping at a shabby, moldy flophouse and paying the electricity bill. “It is impossible to get by in Korea on 600,000 won,” Faina said.

The workers said they were also forced to put money in an installment deposit. They said that the museum made them put installments of 100,000 to 200,000 won in a savings account that would reach maturity after twelve months. The museum authorities explained that they were just depositing money on workers’ behalf because they were not familiar with how banks worked and that they planned on giving the money back. Director Park added that the workers know the password on their accounts. But mandatory deposits are forbidden in Labor Standards Act.

“Mandatory deposits are forbidden by Article 22 of the Labor Standards Act,” said Lee Yo-han, a labor attorney. “This money can be used as leverage to force employees to keep working.”

In the opinion of the performers at the African museum, museum chairman and secretary general for the ruling Saenuri Party (NFP) Hong Moon-jong, is trying to shirk responsibility and shift the blame to the museum director.

“I heard the name of Hong Moon-jong several times, and I knew that he was the owner of the museum,” said Faina. “I think that Hong was obviously aware of our situation. It doesn’t make sense that the owner could not have known about money flowing in and out, including our wages.”

“This does not conform to the facts in several respects, but I will state my opinion after an internal investigation and legal counsel. In front of the Korean people, I deeply regret that such a thing could have happened,” Hong said in a Feb. 11 press release.

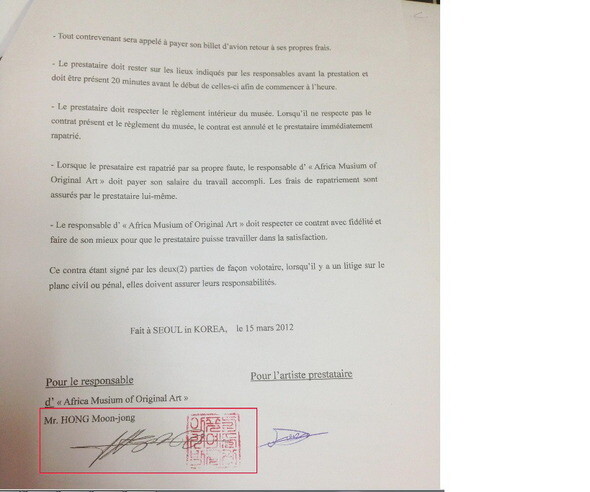

Faina’s work contract was shown to guarantee her a salary of US$650 per month, an eight-hour workday and at least one day off per week and was signed and stamped by Hong Moon-jong. But yesterday morning, Hong said, “Although I’m the chairman of the museum, I‘ve given all management authority to Director Park. All I do is support the museum.”

It was also revealed that after Hong bought the museum and became chairman, the museum received a state subsidy of 47.51 million won (about US$44,100).

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong? [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/8517133419684774.jpg) [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?![[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/6817133413968321.jpg) [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 3[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 4[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda

- 5S. Korea, Japan reaffirm commitment to strengthening trilateral ties with US

- 6Japan officially says compensation of Korean forced laborers isn’t its responsibility

- 7Why Israel isn’t hitting Iran with immediate retaliation

- 8[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- 9[Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- 10[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past