hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

China releases documents showing Japan forcibly mobilized comfort women

By Seong Yeon-cheol and Gil Yun-hyung, Beijing and Tokyo correspondents

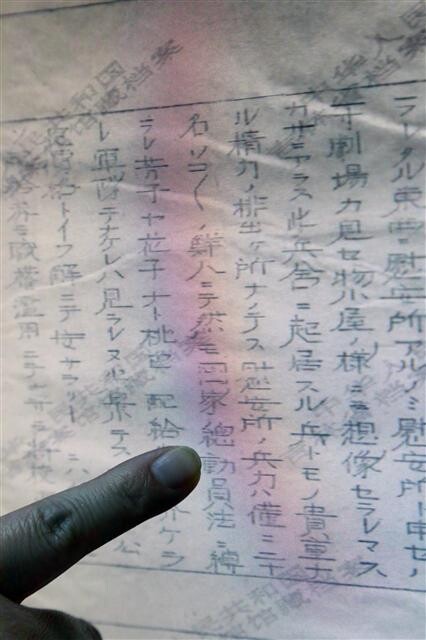

A letter by a Japanese person who wrote that Korean comfort women were mobilized under Japan’s National Mobilization Law was discovered in the Jilin Provincial Archives in China. This is being seen as important evidence showing that the comfort women did not sign up voluntarily in order to make money - as Japan claims - but had actually been officially mobilized by the Japanese imperial army.

The archives are currently sorting through and studying around 100,000 books of documents from the Japanese imperial era left behind by the Japanese Kwantung Army in Manchukuo, a Japanese puppet state located in what is now northeast China. Recently, the archives provided the South Korean media with 25 documents that the archives had already reviewed. The documents are related to the comfort women, women forced to work as sexual slaves for the imperial Japanese army.

The key document is a letter by a Japanese individual that was included in a monthly bulletin prepared by the Japanese military censors operating in the Bei’an region in 1941. “A troop of around 20 Korean women are working at the comfort station. They were forced to serve under the National Mobilization Law,” the letter reads. “They receive pink ration tickets with names like Yoshiko and Hanako.”

The National Mobilization Law was passed in April 1938 in order to control and mobilize manpower, resources, and money after Japan declared war on China in 1937. This law provided the legal basis for regulations about providing work for Koreans, regulations that Japan used to recruit the comfort women.

The material released by the archives includes a large number of documents revealing how the comfort stations that the Japanese army set up in China during the Sino-Japanese War were actually managed. From these documents, it can be inferred that the Japanese military authorities kept track of the number of comfort women in each area and used military funds to maintain an “appropriate” number of comfort women by “purchasing” more women.

Phone records from the Central Bank of Manchou provide evidence that the Japanese imperial army made use of the military budget to traffic comfort women. According to transcripts of phone records, the Japanese military made expenditures using public money under the category of the military comfort women on four occasions between Dec. 1944 and Mar. 1945, for a total of 532,000 yen.

“This is the first time that documents have been discovered that show the amount of money spent to purchase comfort women,” said Mu Zhanyi, assistant director of the archives.

A unit of the military police from the Japanese Kwantung Army that had been dispatched to China filed a report in Feb. 1938 to army headquarters about progress in restoring order in an area around the Chinese city of Nanjing that was under its control. The report details the number of Japanese troops assigned to eight cities and prefectures, including Nanjing, the number of comfort women, the ratio of comfort women to soldiers, and the number of soldiers who used the comfort stations over a ten-day period. The report also states that 36 of the 109 comfort women serving the military in the area around Wuhu were from Korea.

The report for Feb. 28, 1938 notes a shortage of comfort women in the city of Danyang in the middle of February and states the need to recruit comfort women from among the residents of the area.

In the letter included in the monthly bulletin of the Japanese military censors in Bei’an, a Japanese individual wrote, “We can’t lower the wages even if that would be a fairer price. Issuing rations would be an abuse of authority that belongs exclusively to the officers.” The letter vividly illustrates that comfort stations were too expensive for soldiers to use and were only frequented by officers.

The historical value of these records is particularly high because they were directly prepared or stored by the Japanese military during the Sino-Japanese War.

However, these documents do not show that the Japanese military was directly involved in drafting Korean women to serve as comfort women. While the Japanese government currently acknowledges that the imperial army played a direct role in setting up and operating the comfort stations, it holds that no records have been found that demonstrate that the army was directly involved in the process of mobilizing the comfort women.

For these reasons, experts argue that more research should be done into the separate systems used to recruit comfort women in Japan and Korea.

A paper published in Oct. 2013 by Han Hye-in, a researcher at the Center for East Asian History at Sungkyunkwan University, explored the difference between the two systems. According to the paper, comfort women in Japan had to be recruited by brokers who had been authorized to do so by the Japanese army according to legislation about recruitment, while comfort women in Korea could be recruited by the same people who were also hiring nurses in keeping with regulations about Korean workers.

In other words, Japanese comfort women were hired in the framework of state-sponsored prostitution, while in Korea recruitment of comfort women took place on a social level by job brokers. This corresponds to testimony by former Korean comfort women who said that they had found themselves at a comfort station after being told they would be given a good job.

“Given the use of the word ‘troops’ in the documents, we can infer that the comfort women had not come out of a personal desire to make money but had rather been mobilized for public purposes on the orders of the Japanese military,” said Jeong Hye-kyung, a manager for the Committee for Investigating Damage Caused by Forcible Mobilization during Japanese Colonial Occupation and for Supporting Korean and Foreign Victims of Forcible Mobilization.

“These documents are of great significance as they demonstrate that the Japanese imperial army used a forcible process of mobilizing the comfort women,” said Lee Shin-cheol, a research professor at the Center for East Asian History at Sungkyunkwan University.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 3[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 4Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 5Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 6N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 7[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 8[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 9Kim Jong-un expressed ‘satisfaction’ with nuclear counterstrike drill directed at South

- 10[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent