hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Reportage] Gwangju Migrant Workers Center: For 20 years, a home away from the homeland

“Don’t get hurt. Don’t get sick.”

It was 12:20 pm on Jan. 20, and Rev. Lee Cheol-woo was talking with nine Sri Lankan workers at a shelter attached to the Gwangju Migrant Workers Center on the second floor of Mudeung Church in Gwangju’s Gwangsan District.

The workers had spent the day preparing four types of Sri Lankan cuisine, including chicken curry and potato dishes. Kimchi was also available to one side.

Lee, the center’s 65-year-old director, shared conversations with the workers over lunch.

“How many stitches?” he asked Rasantha Ranil, a 32-year-old worker sporting a bandage on his left thumb.

“Ten stitches,” Ranil replied in halting Korean. Ranil has been at the center for over a week since taking time off his job at an Incheon factory because of his injury.

The center, which marks its 20th anniversary this year, has opened a year-round shelter for migrant workers who have no place to stay. Open 24 hours a day, it is available for “friends who have lost their jobs, have suffered from industrial accidents during their stay, have not received wages, or have left their workplace and have nowhere to go.” It’s intended as a homelike environment where visitors can always feel comfortable, with Lee serving as a father figure. Around 10 people visit each day on average.

Those suffering from injuries or illness are assisted with health insurance and other benefits through cooperating hospitals.

Chareet Manohar, 30, has been staying at the center since last month after losing half a finger on his right hand in Apr. 2015 while working at a pipe factory in Jangseong, South Jeolla Province. Although he went through industrial accident procedures as per the factory’s directions, he belatedly learned that he had received a low disability grade. He currently plans to appeal the decision.

“When did you come to Korea?” I asked one of the Sri Lankan guests, who was dressed in a light-green training outfit.

“Oh, it’s been a while. My youth is gone,” he replied, drawing laughs from the gathered crowd.

“This is a really nice place,” said Ajit, 42. “I feel comfortable here. I’m also thankful to Nona.”

“Nona,” an approximation of the Korean word nuna, meaning “big sister,” is what the Sri Lankan workers call center team leader Im Se-mi, 55.

“They said that in their language, nona is a word you use with people you respect. So I insisted that they call me ‘nuna’ more!”

Im, who has been a lay worker at the center since 2001, said she had “learned a lot about Rev. Lee’s warmth. He’s transparent like a pane of glass when he works, yet he doesn’t really show the efforts he makes.”

A shelter for migrant workers in 3D jobs

The center was first launched in Sept. 1997 out of an interest in migrant worker human rights issues. Lee had been affected deeply by a sign he saw in the hand of a Nepali worker in 1995. “Don’t hit me,” it read. “I’m a person too.” He was also shocked by a press conference in which migrant workers in so-called “3D jobs” - dirty, dangerous, and demeaning - showed the stumps of their severed fingers.

“At the time, there were a lot of criticisms about migrant workers being brought here as ‘industrial trainees’ and then being treated like modern-day slaves,” Lee recalled. “They’d take away their ID cards and put them to work without letting them sleep. It was exploitation.”

The issue inspired efforts by human rights and social groups in the Gyeonggi Province cities of Seongnam and Asan and in Gwangju. Around 50 groups nationwide came together to form the Joint Committee for Migrant Workers in Korea. Lee, who took part in Gwangju, became the first chairman of the Gwangju Migrant Workers Center.

Interest in the human rights of migrant laborers is a thread that runs throughout Lee’s career.

Born into a Christian family, Lee graduated from Mokpo High School and studied evangelism with the Presbyterian Church in the Republic of Korea. During the 1970s, while Lee was working in the ministry, he was imprisoned on two occasions for supporting the democratization movement and opposing the dictatorship.

“Back then, I was interested in poor areas and labor issues and in going into those areas and setting up churches for the people that could serve as small communities,” Lee said.

But the Gwangju Uprising in May of 1980 and the ensuing massacre came as a huge shock to Lee. At the time, he was a wanted man, and even though he arrived in Gwangju just before the uprising, he was not able to join with the citizen army. The resulting guilt and shame eventually led him to resolve to lead a different kind of life.

In November of that year, Lee became a minister at Mudeung Church, located near Gwangcheon Industrial Park in western Gwangju. He and his colleagues studied the lives of those who were jailed for their role in the uprising and launched an evening educational program at the church. This became a small community that carried on the torch from the night classes that had played such a big role in the Gwangju Uprising.

Then in 1982, Lee went to seminary at Hanshin University. Around his graduation, he spent a lot of time thinking about what to do, and he became convinced he needed to go back to Gwangju.

He spent a year as a laborer at a foundry in the Singa neighborhood of Gwangju before becoming the main pastor at Mudeung Church in Aug. 1987. Since the Gwangju Uprising, the church had dedicated itself to the work of urban outreach to the city’s factory workers. It also became one of the city’s leading supporters of the labor movement, especially after Kim Sang-jip, 60, who had played a key role in establishing the Korean Christian Workers Alliance in Gwangju, joined the church.

“We also made a school for workers. After the democracy protests in June 1987, several labor unions sprang up at the church almost overnight,” Lee recalled.

The Gwangju Migrant Workers Center is not run to evangelize people. It even removed a cross that had been kept in the shelter, out of respect for the Muslims and Buddhists who might visit.

Each April, the center holds a tteokguk (rice cake soup) party for Sri Lankan workers, who are celebrating a holiday that is equivalent to South Korea’s Lunar New Year. Lee was even awarded a plaque of appreciation from the Sri Lankan government in 2013.

In June 2005, the Gwangju Foreign Workers Health Center was established through the efforts of the Gwangju Foreign Workers Missionary Church, the Foreigner Workers Culture Center, the Gwangju and South Jeolla branch of the Dentist Association for Healthy Society, a group of medical volunteers from Kwangju Christian Hospital, and doctors who belong to outreach groups.

“Lee [Cheol-woo] met with each group that was providing volunteer medical service to foreign workers and proposed that we talk about how to make our treatment plans more specific,” said Lee Geum-ho, director of treatment at the Gwangju and South Jeolla branch of the dentists’ association.

Last year, a total of 2,648 migrant laborers from 10 countries - including Sri Lanka, Cambodia, the Philippines, and Uzbekistan - stayed at the center. The reason that laborers frequent the place so much is because word has gotten out about how actively it supports them.

However, this also shows the continuing difficulties that migrant workers face in South Korea.

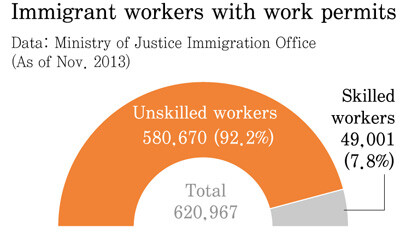

Since the work permit system took effect in Aug. 2004, migrant workers have been able to work in the country for three years and to extend their stay for one year and 10 months.

“Since migrants have to go into debt to work in Korea and since their period of stay is so short, it’s not common for them to settle down,” said Kim Eung-gyu, 46, a head counselor at the Gwangju Migrant Workers Center.

Once migrants have exceeded their legal stay - becoming undocumented workers - their wages go down, and they also lose out on their severance pay.

“When I take workers who haven’t been paid to the Labor Ministry to report their employer, the employer sometimes reports them as illegal aliens. They’re kicked out on the spot,” Kim said.

While the Gwangju Migrant Workers Center receives 15 million won (US$12,500) in aid from the city of Gwangju each year, this is barely enough to pay the staff. Fortunately, the center also gets donations from about 200 people who give between 5,000 won (US$4.19) to 10,000 (US$8.38) won a month. That’s a major help for the center.

“Most of the migrants are well-educated. They can speak three languages, including Korean. But they don’t have a very good impression of Korea. They just think of it as a place to make money,” Lee said. “Some migrants commit socially deviant behavior, but there may be cultural reasons for this. It may be that we’ve failed to help them care about Korean society.”

“We need to respect migrants as members of Korean society who live here just like us,” Lee said. This is a conviction that this man has held during the 20 years he has spent with migrant workers.

By Jung Dae-ha, Gwangju correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 346% of cases of violence against women in Korea perpetrated by intimate partner, study finds

- 4[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 5‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 6Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 7Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 8[Interview] Dear Korean men, It’s OK to admit you’re not always strong

- 9Korean government’s compromise plan for medical reform swiftly rejected by doctors

- 10[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far