hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Expert rebuts Defense Ministry’s claims about THAAD missile interception

A US missile defense expert fired back at claims by the South Korean Ministry of National Defense disputing his contention on that propellant explosion technology seen in North Korea’s Feb. 7 long-range rocket launch could render a Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system useless.

In several recent emails and telephone interviews with the Hankyoreh’s Washington correspondent, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) emeritus professor Theodore Postol delivered a point-by-point rebuttal to what he claimed were erroneous claims by the ministry. Previously, Postol claimed that North Korea could make it impossible to distinguish between an actual warhead and other fragments for THAAD interception if propellant explosion technology were used with the Nodong missile.

In response, a Ministry of National Defense source explained at a Feb. 12 briefing that North Korea’s SCUD missile “wouldn’t be able to function as a missile with an internal detonation device installed because it has an integral structure, unlike the long-range missile.”

“Also, while the Nodong missile might show tracks for various fragments for a few seconds early on if an explosion were installed on the propellant, they would be immediately distinguishable,” the source claimed.

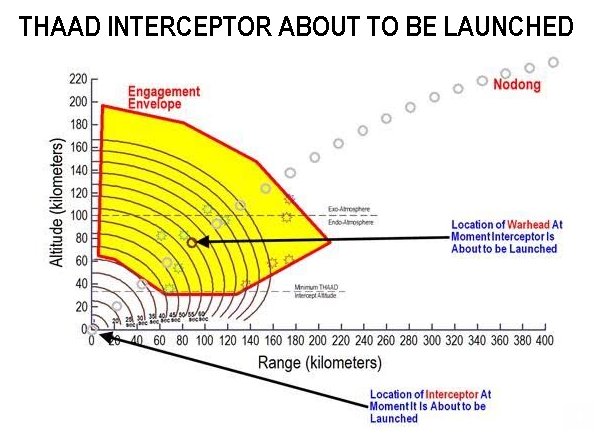

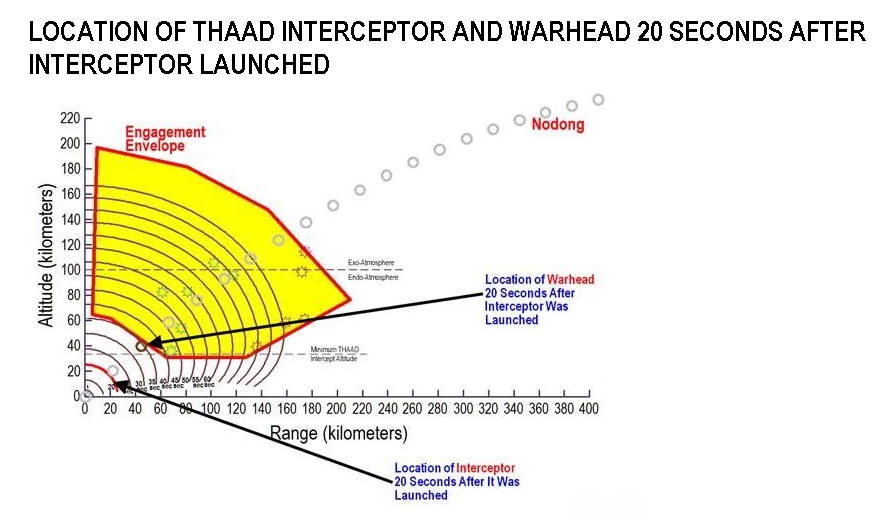

Postol first addressed the factors undercutting the ministry‘s claims about the Nodong missile. In short, if an interception missile were fired after a THAAD radar determination on the warhead and fragments from the missile, the warhead would fall too far in altitude for interception, he explained. In other words, any interceptor launch that came would be too late to be useful.

According to analysis data provided by Postol on the aerodynamic characteristics of objects with different weights, the warhead, fragments of a missile after powered flight, and small metal plates and screws would travel together to an altitude of around 70 km. Above that, air resistance would be slight and the speed of the objects’ fall would be roughly the same. In other words, an interception missile could not be fired until the heavier warhead and lighter fragments reached an altitude of 70 to 80 km, where their aerodynamic speed would change and identification would be possible.

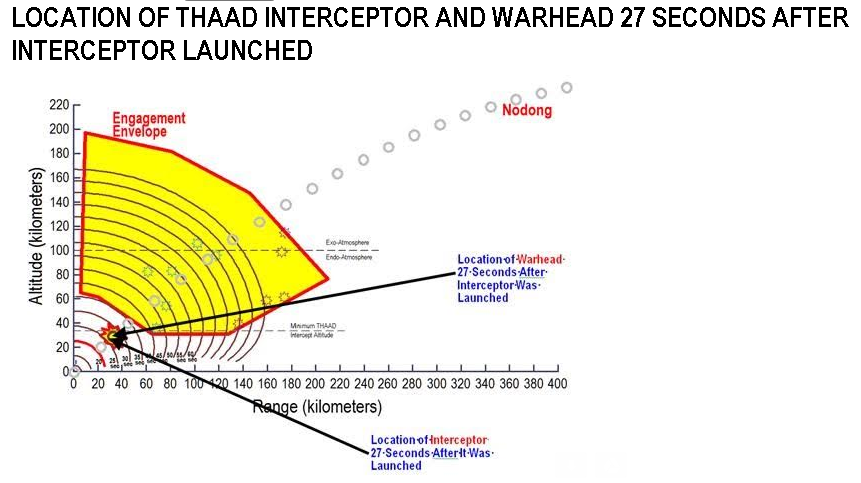

An interception missile could reach a warhead at an altitude of around 30 km within 27 seconds of launch if THAAD radar on the ground made a distinction between the warhead and other fragments and passed launch information about the warhead‘s position and altitude to the interception missile. The problem is that such a point would be 40 km below the minimum interception altitude for an interception missile for the Nodong - meaning a precise interception is effectively impossible.

Ground THAAD radar could, of course, launch an interception missile before the distinction between warhead and fragments is made. This would present problems in two regards. First, Postol explained, even if THAAD radar did make a belated distinction after launching an interceptor, it could not pass on information to the missile once it is in flight. Interception missiles are designed to home in on their target with internal infrared sensors once they approach it after launch. Information transmission has always been an important issue, Postol said.

Without that information, the only time when the interceptor’s sensor could distinguish the warhead from other fragments would come just a few seconds before impact. Before that, it would be impossible for the sensor to make any distinction between the warhead and a decoy.

“This problem with all missile defense interceptors that home using infrared sensors, of course, is described lucidly by Secretary of Defense Ashton B. Carter in [an earlier] published analysis,” Postol said.

Postol also countered the ministry‘s claims that an explosive device could not be installed on a SCUD missile.

“It is not true that the SCUD ballistic missile is fundamentally different in structure from the Nodong,” he said.

Because both missiles basically have a thin, wall-like eternal metal structure, it would be very easy to break them into fragments using an explosive cutting cord, he explained.

“An explosive cutting cord is typically placed tightly around a metal surface that it is to be cut into pieces. An explosion is initiated on one end of the explosive cutting cord,” Postol said of the process.

“The explosive shock propagates along the length of the cutting cord generating gases of extremely high temperature and pressure that simply cut through the metal surface like a hot knife would cut through butter,” he explained.

“This technology is routinely used in rocketry to cut single pieces of metal into multiple pieces,” he added.

Postol went on to say that the decision to deploy THAAD is one “that only the South Korean people can make.”

“However, they deserve to know the real technical facts,” he added.

“If there is no technical benefit to THAAD, then such a decision could have a high cost and no benefit to offset it.”

By Yi Yong-in, Washington correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 3[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 4Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 5Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 6N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 7[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 8[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 9Kim Jong-un expressed ‘satisfaction’ with nuclear counterstrike drill directed at South

- 10[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent