hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

US expert: uranium price falling, why is S. Korea seeking expensive spent fuel processing facilities?

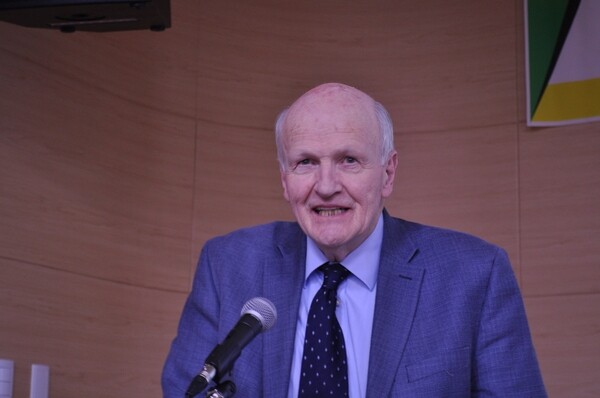

“The price of uranium is gradually falling, and it costs twice as much to acquire spent fuel processing facilities for running a fast reactor. I don’t understand why [South Korea] is trying to acquire such expensive facilities,” said Frank von Hippel, 80, a professor at Princeton University, during a lecture at a seminar called “Truth and Lies about Pyroprocessing” that was held at the Daejeon Youth We Can Center on Feb. 28. Von Hippel is the American nuclear expert who first proposed the term “proliferation resistance.”

“The Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute is trying to develop the two technologies that all other advanced countries have failed to develop, which is to say reprocessing spent nuclear fuel and liquid sodium-cooled fast reactors. While they claim to be pursuing nuclear fuel reprocessing as a way to manage nuclear waste, this doesn’t improve the problem but only makes it worse while incurring tremendous costs,” von Hippel warned.

“I don’t think the Trump administration and the Republicans are going to change the Obama administration’s nuclear policy [of non-proliferation],” he said.

Von Hippel is a member of a Jewish family that migrated from Germany during World War II, and his father, uncles and brothers are all scholars. While von Hippel initially followed the path of pure physics, the debate over the Vietnam War in the 1970s turned him into a socially engaged scientist. After the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in the US in 1979, von Hippel was the first to argue that iodine pills should be distributed to residents. The accident also inspired him to call for the installation of a filtered containment venting system in the containment vessel of nuclear reactors to eliminate the risk of explosions, but the nuclear establishment, represented by the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), ignored these proposals on the grounds that they were too expensive. But the hydrogen explosions during the accident at the Fukushima nuclear power plant in Japan in 2011 proved that his arguments were correct.

By coining the term “proliferation resistance,” von Hippel exerted a major influence on the nonproliferation policy of former president Jimmy Carter, who banned reprocessing, and he also served as Assistant Director of National Security in the White House Office of Science and Technology early in the presidency of Bill Clinton, in 1993 and 1994. In 2006, he established the International Panel on Fissile Materials (IPFM), which has been working toward nuclear disarmament and opposes nuclear weapons, reprocessing and fast reactors.

Pyroprocessing, which was the theme of the day‘s lecture, is one of the technologies for reprocessing spent nuclear fuel that are being researched by the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute (KAERI). The goal of the technology is to use high-temperature electrochemical methods to reprocess the nuclear fuel left over from running a nuclear reactor so that it can be reused as fuel in fast reactors.

“In 2001, Vice President Dick Cheney approved a request by the Department of Energy’s nuclear research institute to be allowed to develop pyroprocessing with KAERI. The institute claimed that pyroprocessing was better for nuclear nonproliferation than the existing reprocessing methods. The institute argued at the time that the pyro method couldn‘t be used to remove the plutonium from spent nuclear fuel for use in nuclear weapons, but that’s not true,” von Hippel said.

“The Idaho National Laboratory promised to process 25 tons of spent nuclear fuel using pyroprocessing in five years, but they only processed five tons in 16 years, which cost a huge amount of money,” he went on to say.

The plan to reprocess spent nuclear fuel and to build fast reactors derives from false predictions about the future, von Hippel explains. In the 1950s, Americans expected that energy demand would double every decade, but the current energy demand is only twice what it was in the 1960s. The American nuclear energy establishment projected in the 1960s that nuclear energy would cover 100% of future energy demand, but at present nuclear power only provides 20% of energy in the US and just 10% of energy worldwide.

The plan to reprocess spent nuclear fuel for use also derived from concerns about the depletion of uranium reserves and rising prices. But the dreaded rise in prices never materialized because predictions about the rate of increase of nuclear plants were way off and because the output of uranium mines has not decreased. “Currently, the cost of uranium only accounts for 1% of the cost that goes into producing electricity at nuclear plants. Even if spent nuclear fuel is reprocessed and used at fast reactors, it will only be about 2%. Not only is this a small percentage of the total cost, but it will only make the cost of generation more expensive. I don‘t know if it’s necessary to acquire high-cost facilities,” van Hippel said.

Along with the high cost, there are high risks, which means that hardly any countries are interested in building fast reactors, von Hippel contends. France’s fast reactor Superphenix cost 100 trillion won to develop but only operated at 8% before being decommissioned, and Japan’s Monju nuclear plant operated at just 1% for 20 years before it was decided last year to shut it down. The UK is also planning to end operations in 2018. China operated a pilot fast reactor in 2011, but after producing 20kg of plutonium, a small amount, it concluded that the benefits were marginal and suspended the program. Russia continues to operate these reactors, but there have reportedly been 15 fires at sodium fast reactors.

“The Obama administration has held to its conclusion that it‘s not necessary to reprocess spent nuclear fuel. I don’t think the Trump administration and the Republicans are going to deviate from Obama’s stance on nuclear policy. They will probably resume construction on the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository and maintain the existing nuclear reactors, but I don’t think they‘ll build any new ones,” von Hippel said.

In von Hippel’s view, the most affordable policy for managing spent nuclear fuel is first storing nuclear waste in dry casks and then burying those casks deep underground in disposal sites that have been prudently designed with engineered barriers.

“The South Korean nuclear establishment maintains that the country is too small to hold a disposal site for nuclear waste, but there’s already a 7,000-ton dry storage facility at the Wolseong Nuclear Reactor. That’s equivalent to the amount of spent nuclear fuel accumulated from light water reactors,” von Hippel added.

“In 2006, the National Academy of Sciences published a report commissioned by Congress in which it proposed that after five years of cooling in storage pools spent nuclear fuel could be stored in dry containers and put back in open-rack storage. But even after this, Congress did not take any measures until after the Fukushima disaster in 2011, when it launched a review.”

By Lee Keun-young, senior staff writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 3‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 4Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 5[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 6[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 7[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 8[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 9Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 10Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US