hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Japanese photojournalist’s book chronicles hideous crimes of the past

The first feeling that South Korean readers are likely to get from this book, written by Japanese photojournalist Takashi Ito, 65, is shock. They’ll get a glimpse into how the aggressors can be saved from their hideous crimes of the past. The testimonies of the 20 former comfort women from North and South Korea that are included in this book (originally titled “The Sadness of the Rose of Sharon”) are bathed in blood – they are, in the words of the writer, “so shocking that I lost my desire to cover the story.” That shock is communicated through Ito’s photography and his writing style – marked by brevity and grace, with little in the way of rhetoric.

While still in their teens, these women were taken to a strange and distant land where they were isolated and forced to serve dozens of soldiers on the battlefield every day, all day long. After being scorned and treated literally worse than beasts, many of these women were killed, some beaten to death and others decapitated. While historical revisionists on Japan’s far right make the far-fetched claim that these women had volunteered to be prostitutes and had not been compelled, these claims only work against them. The survivors have testified that a large number of them were kidnapped, but the deceptive promises about finding work for the women and the cruel acts of “comfort” the women had no choice but to perform in a confined space are also clearly examples of compulsion.

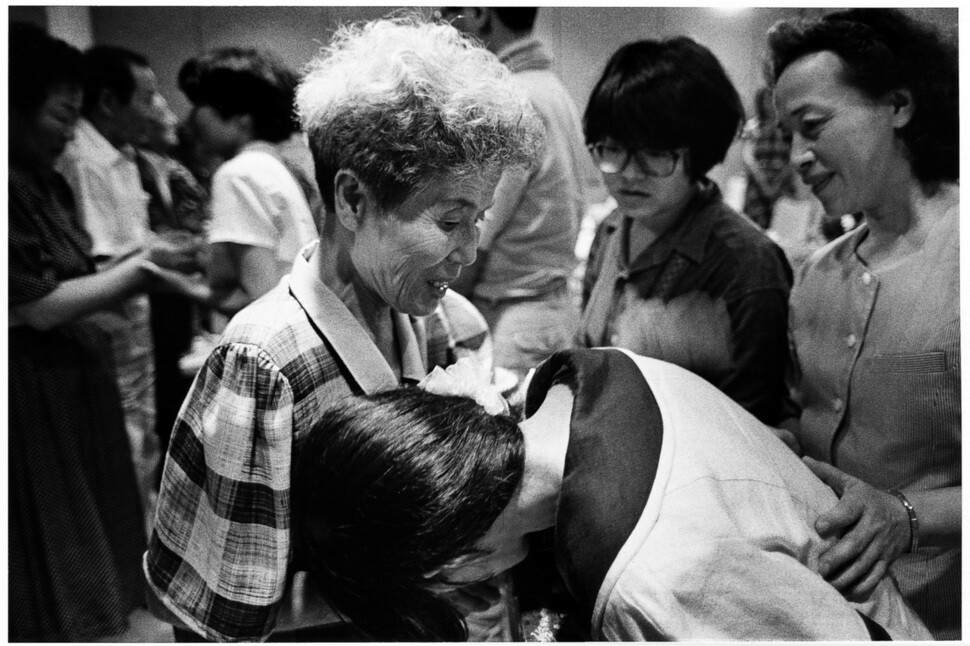

The tearstained testimonies of these women, who were not welcomed home even after they returned alive after their hellish experience, in fact serve as a jarring revelation of how ignorant we have been about them. Time and time again, the women tried to stop testifying: Hwang Geum-ju “picked up the tape recorder during an interview and flung it away,” while Park Yeong-sim said she didn’t want to talk to a Japanese person. Kim Yeong-sook even screamed about wanting to “go to Japan and stab all the Japanese with a knife.” It makes one ashamed to think of how Ito has painfully listened to these women’s stories and brought them to the attention of the world for decades through his writing, photography and videos.

Ito started out as any other ordinary Japanese person. Given his interest in documentary photography, he had been visiting Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1981 to cover the damage caused by the atomic bombs dropped by the US when he received an “incredible shock” to learn that about 70,000 Koreans had been exposed to radiation during the bombing. That was when he started reporting on Korean and Japanese victims of the atomic bombing, and he met victims of forced labor and women who had been taken to munitions factories as members of the Korean Women's Volunteer Labor Corps, only to be drafted as comfort women. The scope of his reporting expanded to include North Korea, China, Southeast Asia and Russia, and again and again he encountered the “violent rage” of the victims of Japan and the Japanese.

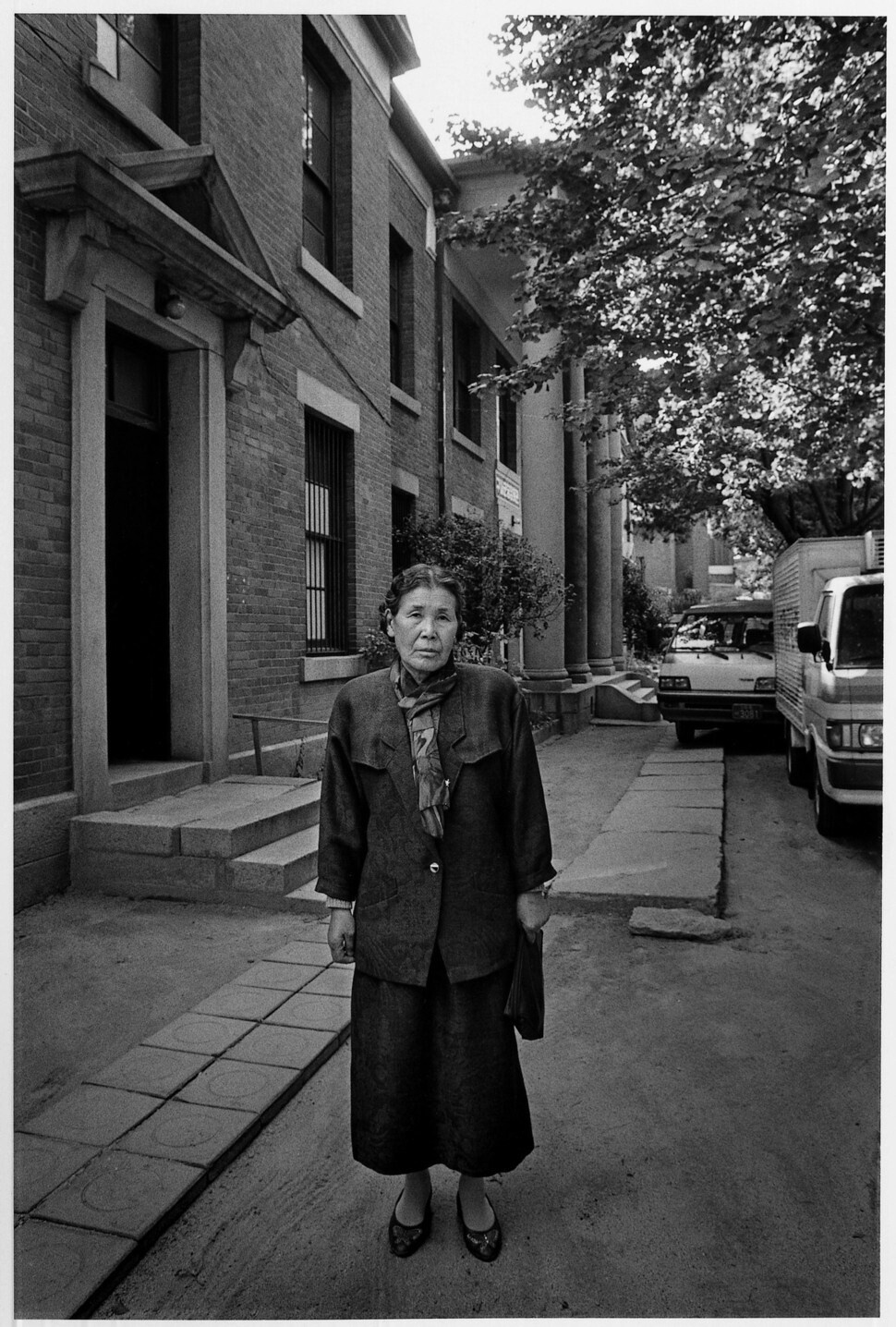

Ito has met more than 800 victims of Japanese aggression, just counting victims from the Asia-Pacific region. It was during his reporting, on Aug. 14, 1999, that a shocking incident occurred: Kim Hak-soon became the first former comfort woman for the Japanese military to publicly reveal her identity. This broke the taboo that had silenced both the aggressors and the victims, and thousands of victims in various parts of Asia came forward to testify. “The essence of the war of aggression perpetrated by Japan based on its ideology of disdain for Asia was clearly manifested,” Ito wrote.

After that, Ito met more than 90 former comfort women, starting in South Korea, (including Kim Hak-soon) and continuing to North Korea, China and Southeast Asia, along with people from the Netherlands. His book contains the stories of 20 former comfort women from those he has interviewed since the early 1990s, nine from South Korea and 11 from North Korea. When they were interviewed, these women were already in their 80s, and none of them are still alive today. While 238 former comfort women were registered with the South Korean government, the death of Lee Soon-deok (who at 100 years old had been the oldest of them) on Apr. 4 brought the number down to 38.

The stories of the barbarous acts perpetrated by the Japanese soldiers are chilling – some women were stabbed with katana blades, the bodies of others were defaced with tattoos and still others who refused to follow instructions were ruthlessly beaten before being chopped into pieces to set an example. The witnesses said that, when Japan was about to lose the war, dozens of comfort women, and sometimes even more than a hundred, were massacred in an attempt to destroy evidence.

It appears that the majority of Japanese today are aware of Japan as the victim but don’t know much about Japan as the perpetrator, just as the author used to be. Perhaps the malicious comments online about the former comfort women are also a result of their ignorance about the ugly deeds of the past of which their country is guilty. Their ignorance and disdain has probably been fuelled by the narrow-mindedness and lack of sympathy on the Korean Peninsula, where people neither listened to the stories of the victims nor gave them much help. Could that be why the Japanese have come to resemble the world view and the values of the perpetrators?

“The reason I continued to cover this story was because I was certain that proving the grave crimes of the Japanese state was critical for Japan’s present and its future. […] The job of Japanese journalists is to share with a large audience the voices of those who were harmed by Japan in the past,” Ito wrote.

By Han Sung-dong, senior staff writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 4Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 5US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 6[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 7All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 8[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda

- 9Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 10More South Koreans, particularly the young, are leaving their religions