hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Interview] “They aren’t my blood, but they’re all my children”

War changes the trajectory of lives. Such was the case for Seo Jae-song, The 88-year-old native of Deokjeok Island in Incheon’s Ongjin County was admitted to the National Fisheries College of Busan (now Pukyong National University), but ended up drafted into the military and taking part in the Incheon landing (part of the Battle of Incheon) after the Korean War broke out. When he was discharged four years later, he returned to his home on Deokjeok Island to find the village there filled with refugees. The population back then was over 10,000 (today it is just over 1,500), many of them children. The orphans wept so much he thought the island might float away.

“Around 1955, there were 1,000 children in this neighborhood alone,” said Seo when he met a Hankyoreh reporter at the island village of Seopo on May 10.

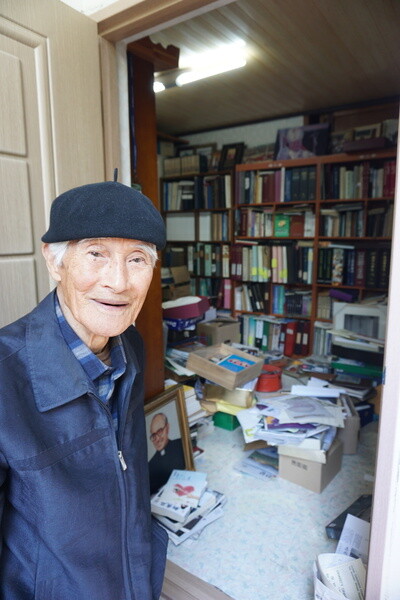

A corner of one room in Seo’s house on Deokjeok Island is filled with records of the mixed-race children he helped adopt to the US and other countries.

Seo gave up on returning to school and decided to remain on the island. Soon the April 19 Revolution of 1960 occurred, and villagers ousted their Liberal Party-affiliated chief and elected Seo in his stead. After serving as village chief, Seo was working as township secretary when he was visited by Father Benedict Zweber (Korean name Choe Bun-do), a German-American priest called the “Albert Schweitzer of the West Sea islands.” In 1962, Zweber became the head priest for the Yeonpyeong Island parish church, which had jurisdiction over 22 smaller churches in the West (Yellow) Sea region. He came to visit the Catholic Seo in his office with a proposal. Six months later, Seo quit his career as a government employee to join Zweber in caring for war orphans. Seonggajeong, the orphanage Seo and his wife set up on Deokjeok Island, became home to around two dozen children who had lost their parents to war, typhoons, or disease.

Later, the couple took over duties at the St. Vincent Home in the Sangok neighborhood of Incheon’s Bupyeong district. They served as directors with over 100 children under their care until the home was closed in 1997. Around 1,600 children were adopted to the US, Canada, and elsewhere through the home.

As the site of a US military base, Bupyeong was home to many mixed-race children. With their mixed ethnicity and no parents, the children were seen as nuisances - if they were seen at all. With nowhere to go at home, they had to be sent overseas.

Over the years, the adoptees began coming back to see Seo. The first visit came in 1982 by brothers Hong Seong-jae and Hong Seong-heon, who had been adopted to the US as elementary school students.

“They had been adopted by different homes, and they came one day to find their biological parents. At first, I had only written names and basic information in the children’s records, but I realized that wouldn’t do,” he explained.

“I felt that I had to write down something proper [as a record for children who might come back as adults to find their parents], so I began adding various details. They aren’t my blood, but they’re all my children,” he said.

Seo showed an old folder containing photos of individual children along with their name, sex, date of birth, resident registration number, place of register, address, guardian contact details, additional comments, and the address of the home where they were adopted. A total of 1,073 records were included for adoptee birth dates between 1957 and 1996.

Seo’s records served as a resource for the 2016 “Other Immigrants: Overseas Adoptees” special exhibition by the Museum of Korean Emigration History. Last year, they were scanned in their entirety by the Ministry of Health and Welfare’s Korea Adoption Services (KAS). KAS has been working to gather and computerize analog records from remaining or closed child protection facilities to assist overseas adoptees in their search for their roots. As of last year, the agency had assembled 39,000 records from 21 institutions. Seo provided KAS with his records, which he had preserved even after leaving his management post at St. Vincent Home.

“Mr. Seo is the only individual who has preserved records at this kind of scale,” a KAS source said.

The number of South Korean adoptees stood at 170,000 as of late 2016. With KAS’s archive scanning effort scheduled for completion around next year, it received around 1,600 requests last year alone for help finding biological parents.

“We’ve succeeded in finding whereabouts for around 1,000 cases, but only around 15% of the time do [adoptees] actually meet their birth parents,” a KAS source said.

South Korea is a party to the Hague Adoption Convention to promote adoptee rights, but continues to suffer under its reputation as an “exporter” of children. Children are also adopted overseas from countries with lower per capita national incomes such as Malaysia, Bangladesh, or Pakistan, but 374 out of 1,057 South Korean adoptees as recently as 2015, or 35.4%, were adopted overseas. In 2005, the South Korean government designated May 11 as “Adoption Day.” On May 13, the Ministry of Health and Welfare is holding a commemorative event for the day at Daeyang Hall at Seoul’s Sejong University. World-renowned guitarist Denis Sung-ho Janssens, who was adopted by parents in Belgium, is among those scheduled to attend.

By Park Ki-yong, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 346% of cases of violence against women in Korea perpetrated by intimate partner, study finds

- 4[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 5‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 6Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 7Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 8[Interview] Dear Korean men, It’s OK to admit you’re not always strong

- 9Korean government’s compromise plan for medical reform swiftly rejected by doctors

- 10[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far