hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[News analysis] Ethnic Koreans in Japan shut out from visiting their homeland

Do you know about the “Chosen-seki” nationality in Japan? This is the label that Japan gave to Koreans (that is, people from the Korean Peninsula) who were living in Japan after it surrendered to end World War II and its colonial rule over Korea came to an end. The Chosen-seki have no connection with North Korea (despite the similarity of the two words in the Korean language). During the presidencies of Kim Dae-jung (1998-2003) and Roh Moo-hyun (2003-08), these Chosen-seki (ethnic Koreans in Japan that have neither Japanese nor South Korean nationality) were basically allowed to freely visit South Korea. But during the subsequent nine years of conservative governments (from 2008-16, under presidents Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye), they were effectively denied access to their homeland. Not only the Chosen-seki but also civic groups, legal experts and scholars are asking the administration of President Moon Jae-in to reform the system.

“I want to return to my home, Jeju Island. I want to bow before my ancestors’ grave and show my children.”

“The painful and unfair thing is when it’s the people of our home who are discriminating against us, rather than Japan or foreigners. We’re tired and we’ve suffered enough from discrimination ever since our grandparents’ day. I wish the people of our homeland would just stop trampling on us.”

Earnest pleas from Zainichi Koreans (ethnic Koreans from Japan) appeared on the pages of a group chat room set up on social media by the group Association for Immigration by Chosen-seki Zainichi Koreans in Japan to request that they be allowed to travel freely to South Korea. The association stated its goal at a July 12 press conference in front of the office of Gwanghwamoon1st in Seoul’s Jongno district, before delivering a “policy proposal for the unconditional free transit of Chosen-seki Zainichi Koreans” to the committee with signatures from 1,210 individuals and 15 groups. Gwanghwamoon1st office is under the governance planning advisory committee, which plays the role of presidential transition committee, receiving requests or petitions from May 25-July 12.

Homeland off limits because of Chosen-seki status

When a Hankyoreh reporter visited the Jeju National University Center for Zainichi-Jeju People on July 12, 38-year-old researcher Kim Tae-sik, a third-generation Zainichi Korean, was submitting a petition to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs website requesting that his wife, 36, be permitted to visit South Korea. The wife, also a third-generation Zainichi Korea hailing from Jeju, requested a tourist visa the same day from the South Korean consulate in Tokyo to “visit my home and see my husband.”

“My wife, who is a lawyer in Japan, has trouble entering South Korea because of her Chosen-seki status,” explained Kim, who married his wife in Nov. 2016, in his appeal to grant her entry.

“Her Chosen-seki father didn’t acquire South Korean citizenship, so she didn’t either. I think she felt more of a sense of obligation not to change [her citizenship] as a daughter, since her father wanted to go home much more than she did and he suppressed it. Please let my wife visit the homeland she has longed to see so she can visit her ancestral gave and see her husband.”

Kim previously had Chosen-seki status himself. He visited South Korea a total of nine times, the first of them for the 2002 Asian Games in Busan, before finally acquiring South Korean citizenship in Nov. 2010 in the wake of North Korea’s shelling of Yeonpyeong Island. Then working as a researcher at Seoul National University, he made the decision after he traveled to Japan for a former classmate’s wedding and the consulate refused to grant him any more tourist visas.

Chong Young-hwan, a Meiji Gakuin University professor and third-generation Chosen-seki Zainichi Korean whose book “Who Is Reconciliation For?” critiques Sejong University professor Park Yu-ha‘s “Comfort Women of the Empire,” also tried to visit South Korea in July 2016 for a book release party, only to have the Ministry of Foreign Affairs refuse to grant a tourist visa. Kim Seok-beom, a 91-year-old Zainichi Korean novelist from Jeju who was awarded the first Jeju April 3 Peace Prize during an Apr. 2015 visit, attempted to attend book release parties in Seoul and Jeju that summer and fall, but was denied entry - showing that the standards for allowing entry vary even for specific people.

Chosen-seki status a legacy of colonial rule

Chosen-seki status is a painful legacy of the Japanese occupation endured by from 1910-45. It is a foreigner registration status assigned uniformly by the Japanese government to all people from the Korean Peninsula who remained behind in the country after Korea’s liberation - more regional symbol than nationality. After being denied suffrage with a 1945 amendment of election law, Zainichi Koreans were registered as foreigners in accordance with the Alien Registration Ordinance proclaimed in May 1947; for convenience, they were listed as “Chosen-seki,” meaning “Korean domicile.” Taking place before the South and North Korean governments were formed on Aug. 15 and Sept. 9, 1948, this meant all Zainichi Koreans were registered as Chosen-seki. It did not mean, as is often misunderstood, that Chosen-seki status is equivalent to North Korean citizenship.

With the Treaty of San Francisco signed with the World War II Allies coming into effect in Apr. 1952, the Japanese government unilaterally stripped Zainichi Koreans of their citizenship, leaving them stateless. The Jan. 1966 signing of Agreement Between Japan and the Republic of Korea Concerning the Legal Status and Treatment of the People of the Republic of Korea Residing in Japan seemed to grant stable legal status, allowing people with South Korean nationality to request permanent residency. But the controversy continued.

“The South Korean government has customarily regarded Chosen-seki status as equivalent to North Korean citizenship and demanded that [holders] change their citizenship,” explained Cho Kyung-hee, a Sungkonghoe University researcher from a Chosen-seki background who studies Zainichi Korean issues.

“The Chosen-seki issue isn’t just an issue for the holders themselves - it’s an ongoing issue that shows the current historical standing of Zainichi Koreans as defined by Japanese colonial rule and the division of South and North Korea,” Cho said.

According to statistics obtained from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs by the office of Minjoo Party lawmaker Kang Chang-il (Jeju City-A), around 457,700 Zainichi Koreans held South Korean citizenship as of late 2015, while 33,900 held Chosen-seki status.

Chosen-seki Zainichi Koreans have numerous reasons for not adopting South Korean citizenship. Some are closely tied to the General Association of Korean Residents in Japan (Chongryon), which is itself closely tied to North Korea. Others hold on to Chosen-seki status because they have relatives and family in North Korea after past repatriation efforts. Still others choose to keep Chosen-seki status regardless of Chongryon because they want to be citizens of a unified homeland. With the third generation of Zainichi Koreans, pride has also come to be a bigger issue than convictions.

“I felt very conflicted,” said Kim Tae-sik of his changing to South Korean citizenship. “I felt bad for my friends who can’t come to South Korea because they haven’t changed their Chosen-seki status.”

“My father is still Chosen-seki. It‘s not a matter of ideology - he just doesn’t want to change,” Kim added. “I think it’s a matter of pride.”

Kim Young-hwan, head of the external cooperation team for the Institute for Research in Collaborationist Activities, explained, “There’s a sentiment that both South and North were their homelands before colonization, and there‘s also the practical concern that people with family in North Korea won’t be able to contact them if they adopt South Korean citizenship.”

“In some cases, it‘s about political convictions, while in other cases they don’t change because they just don‘t want to.”

Homeland-coming blocked after conservatives take office in South Korea

To enter South Korea, Chosen-seki Zainichi Koreans must have a South Korean government-issued tourist visa. Article 10 (Guarantee of Entry of Overseas Korean Nationals, etc.) of the Inter-Korean Exchange and Cooperation Act states, “If a Korean national residing overseas who possesses neither a foreign nationality nor a passport of the Republic of Korea intends to visit and depart from South Korea, he/she shall carry a tourist visa as prescribed in Article 14 (1) of the Passport Act.” The purported aim of the system is to guarantee entry to Zainichi Koreans without citizenship - but it has repeatedly served as a barrier for Chosen-seki Zainichi Koreans trying to enter.

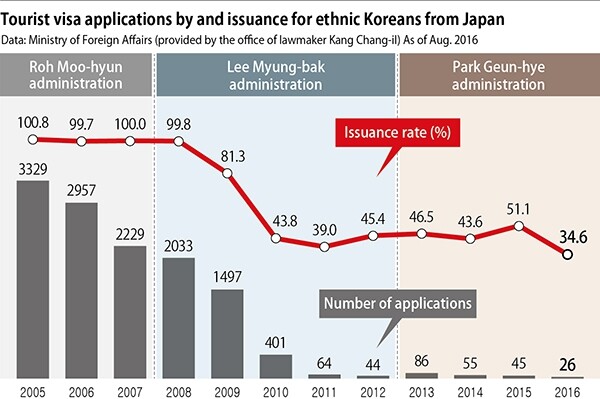

Indeed, the number of tourist visas applied for by and issued to Chosen-seki Zainichi Koreans dropped steeply under the Lee Myung-bak (2008-13) and Park Geun-hye (2013-16) administrations. As Seoul increasingly refused entry to the Chosen-seki Zainichi Koreans, who were regarded as equivalent to holders of North Korean citizenship, a clear trend of avoiding South Korean visits altogether emerged. Parliamentary audit data acquired from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs last year by Kang Chang-il’s office show a marked difference in the number of tourist visas applied for by and issued to Chosen-seki Zainichi Koreans under the Roh Moo-hyun administration (2003-08) and the Lee and Park administrations. During the Roh administration year 2005, 3,329 certificates were applied for and 3,358 granted, for a ratio of 100.8% (including certificates applied for in 2004 and granted in 2005). For the first Lee administration year in 2008, 2,033 were applied for and 2,030 issued, for an issuance rate of 99.8%, meaning that nearly every application was approved.

But in 2009 - the year the Lee administration began working all out to reverse the Roh administration‘s policies - the numbers dropped to 1,497 applications and 1,218 issued. By 2010, applications were down to 401, or nearly a quarter the number for the year before. The number of visas actually issued also fell sharply to 176 (43.8%).

With the conservative administrations’ arrival resulting in major difficulties in tourist visa issuance for Chosen-seki Zainichi Koreans, the number of annual applications dropped below 100 in 2011, while the issuance rate fell below half. Under the Park administration last year, the issuance rate as of August was the lowest ever at 34.6% - nine visas issued for 26 applications. Analysts saw this as meaning free entry to South Korea for Chosen-seki Zainichi Koreans was all but blocked for the nine years of the Lee and Park administrations.

Numerous cases of human rights infringements also surfaced during the certificate issuance process, including high-pressure interviews and demands that applicants adopt South Korean citizenship.

“When I applied for a visa at the consulate, I was pressured to sing the national anthem and sign an oath. I didn’t know it would be so difficult to go to my country, my homeland,” said one Zainichi Korean.

Choi Sang-gu, secretary-general of the Korean International Network (KIN), said, “As the number of entry refusals increased, more and more Chosen-seki Zainichi Koreans began not even applying anymore. In many cases, they just give up because they’re not going to get to go anyway.”

Cho Kyung-hee noted, “The standards for tourist visa refusal are vague, with no explanations or basis given. Instead of considering the historical situation of Zainichi Koreans, they’re applying an excessive security-based reasoning that’s even more intense than what operates internally in South Korea.”

Kim Young-hwan said, “Zainichi Koreans who have taken Japanese citizenship are allowed to visit freely. It’s ironic, and unfortunate, that Chosen-seki Zainichi Koreans have been unable to visit South Korea for close to ten years.”

Kim Myung-joon, secretary-general for the group Mongdang Pencil: People Working with Korean Schools, said, “The ’Chosen‘ label is now emerging as a serious issue causing pain to Zainichi Koreans. Many of the Zainichi Koreans are elderly people who would like to visit their homeland but can’t.”

Civil society takes action

The association behind the July 12 policy proposal to the Presidential Transition Committee was formed in the wake of Chong Yong-hwan being denied entry to South Korea in July of last year. Its members include groups such as MINBYUN-Lawyers for a Democratic Society, the Public Interest Human Rights Legal Defense Center, the Institute for Research in Collaborationist Activities, Mondang Pencil, and KIN and individuals like former Ritsumeikan University professor Suh Sung and attorney Jang Wan-ik. Among the ideas presented in its policy proposal on July 12 were amendment of the Passport Act to loosen tourist visa issuance review standards for stateless Koreans living overseas and allow applications for extensions, amendment of the Overseas Korean Act to include the overseas-residing stateless Koreans currently not regarded as overseas Koreans, and development of Ministry of Foreign Affairs guidelines to prevent human rights infringements during the tourist visa application process.

“There are reports of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs abusing its discretionary powers in politicized ways during the entry review process, such as forcing people to [sing the] national anthem or [sign] oaths or asking insulting questions,” said Song Sang-kyo, director of MINBYUN’s Public Interest Human Rights Legal Defense Center.

“These are illegal acts that are not lawfully permitted,” he stressed.

“Many overseas Koreans have been unable to enter South Korea because their tourist visas were denied for unjust reasons. If the Ministry of Foreign Affairs recognizes the seriousness of this problem, it needs to be forward-thinking and move quickly to develop human rights-friendly administrative guidelines before they are legislated,” Song said.

Song also pledged to “use various methods to investigate the situation, including information disclosure requests on human rights issues during the tourist visa issuance and passport review processes.”

By Huh Ho-joon, Jeju correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1Samsung subcontractor worker commits suicide from work stress

- 2Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 3No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 4‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 5[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 6Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 7Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 8US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 9[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 10[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?