hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Tragic death of a Nepali migrant worker

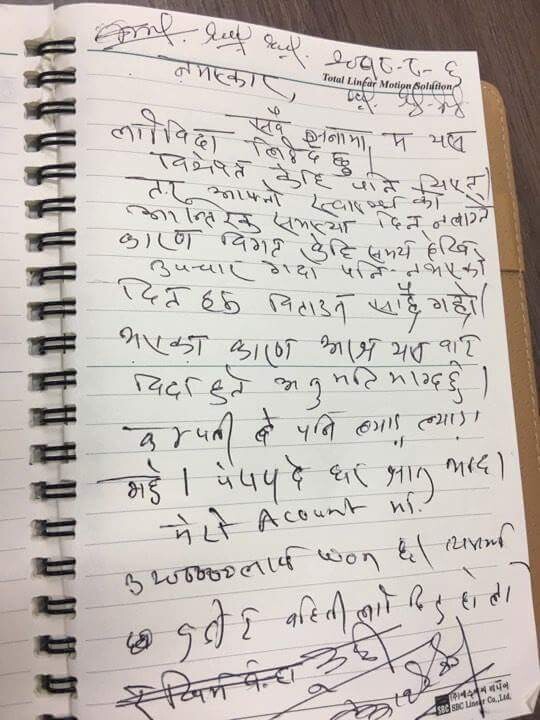

Early in the morning on Aug. 7, a letter was found in the factory dormitory of a parts manufacturer in Chungju, North Chungcheong Province. It was a suicide note written by Keshav Shrestha, a 27-year-old Nepali migrant worker who was found hanged on the dormitory’s roof that same morning. In crooked Nepali script across the pages of a spiral-bound notebook, Shrestha had written his farewell to the world.

“Hello, everyone. I am saying goodbye to the world today. I’ve had health problems and I can’t sleep. I’ve been receiving treatment, but it hasn’t gotten better. This time has been so difficult for me, and today I decide to leave this world. I’ve had to deal with stress at work, I don’t want to go to another factory, and even though I’ve tried to go to Nepali for treatment, I haven’t been able to.”

Shrestha arrived in South Korea in early 2016. He had been married for just three to four months. His wife and younger sister saw him off as he left Nepal. After finding work at a parts manufacturing factory, he worked for 19 months under a system of two day and night shifts of 12 hours each.

But around three to four months ago, he began suffering severe insomnia. Around May, he changed his work pattern to only perform duties in the daytime. Still, he spent more and more nights wide awake.

“I lent him a quiet space where I thought he might be able to sleep, but his health didn’t get any better. He often talked about wanting to work somewhere else,” said a Nepali worker who had been close to Shrestha.

According to the Cheongju Migrant Workers’ Human Rights Center and the migrant worker shelter Cheongju Nepal Shelter, Shrestha met with company management staff twice last week.

“I want to change workplaces. If that won’t work, I’d like to go to Nepal first for treatment and then come back and work for a different company,” he said.

In response, the management staff proposed “moving the team.” When Shrestha refused, the staff told him he should go back to Nepal and instructed him to get a plane ticket there as part of procedure.

On Aug. 7, Shrestha talked until three in the morning with colleagues, complaining he felt “no meaning in life” and had “no choices.” When he failed to show up for morning calisthenics, his dormitory roommate went looking for him and found his cold body. Toward the end of his note, Shrestha mentioned the family he was leaving behind in Nepal.

“There’s 3.2 million won [US$2,800] in my bank account. Please give that money to my wife and sister,” he wrote.

News of Shrestha’s death spread to the outside when Sunita Pandey, the 40-year-old manager of Cheongju Nepal Shelter in North Chungcheong Province, translated the note into Korean and shared it on the Facebook page for Nepal with Safe, a Cheongju youth migrant worker human rights organization.

“A person has died because of the employment permit system,” Nepal with Safe and Pandey wrote in the post.

“[Shrestha] was in great physical pain from difficult work and stress. He asked several times to change workplaces or to be allowed to go to Nepal briefly for treatment, but the company’s foreigner management team would not allow his request,” they added.

“Foreign workers subject to the employment permit system are institutionally prevented from changing workplaces as they wish without the permission of their employer, even if the company where they are now is not good,” they explained.

The Act on the Employment, etc. of Foreign Workers restricts migrant workers as a rule from changing workplaces after entering South Korea through the employment permit system. A worker may change workplaces up to three times in three years, but only in exceptional cases. Workplace changes are allowed only in cases where the employer grants approval, or in exceptional instances such as nonpayment of wages and other Labor Standards Act violations by the employer.

In an Aug. 9 telephone interview with the Hankyoreh, the company management staff said Shrestha had “never said outright that he wanted to change workplaces.” “He said, ‘I want to quit and go back to Nepal,’ and we communicated to him on Aug. 7 that we should discuss the related procedures, including getting a plane ticket for the Labor Ministry reporting process,” the company explained.

“We have also had many foreign workers here who have gone back to visit their home countries. There’s no reason for us not to give permission,” it said.

Shrestha is not the only Nepali migrant worker to have died recently. Pandey heard about six death notices for Nepali workers in May and June alone. On May 20, two young workers were working on the cleaning team at a pig farm in Gunwi County, North Gyeongsang Province, when they were asphyxiated by manure gas. In South Gyeongsang’s Geoje area, a factory worker in their twenties suffered a fatal four-story fall. Another worker died of a heart attack in their sleep. Two workers took their own lives after their employee refused to grant permission for a workplace change.

“Many people are dying on the job, and many others are taking their own lives after battling their employers over blind spots in the employment permit system,” Pandey said.

“More and more, they are coming to feel that they are better off dead than taking any more of this stress,” she added. “I don’t know how I’m going to tell another family about this.”

By Ko Han-sol, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 4[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 5Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 6All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 7US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 8Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 9[Photo] Smile ambassador, you’re on camera

- 10[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes