hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Who was Song Sin-do?

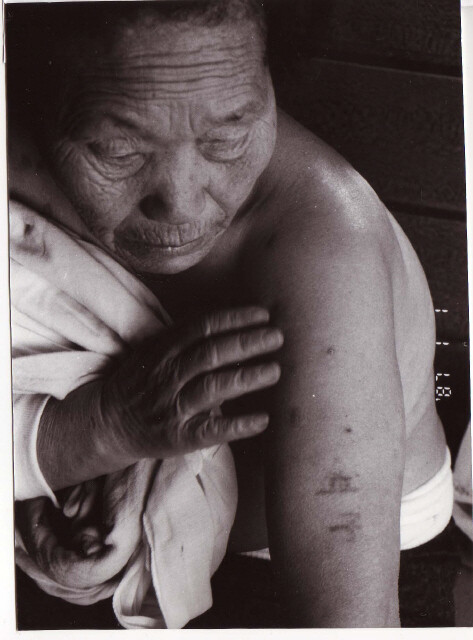

The knife scars left on her sides and thighs and the tattoo on her arm that read “Kaneko” (her name at the comfort station) bore witness until the end of her life to the things Song Sin-do had suffered. After being abducted by the Japanese army at the age of 16, Song rotated through comfort stations at various cities in China for seven years and was forced to “comfort” countless Japanese soldiers. She was impregnated several times and gave birth to two children. But because she could not take care of them, she surrendered them to Chinese families and parted with them forever.

While she was making the rounds of comfort stations in China, Song heard about Japan’s defeat in World War II. But with nowhere to go, she accepted an offer of marriage from a Japanese soldier and followed him to Japan. She boarded a ship in the spring of 1946 and reached Hakata Port in Fukuoka, but the soldier proved unfaithful and deserted her. Song later met a Korean living in Japan, and they lived together until 1982.

The world was made aware of the existence of this woman by conscientious Japanese citizens. In 1992, Japanese government documents were discovered proving that the Japanese army had been involved in the compulsory mobilization of the comfort women. After this, four Japanese civic groups set up a hotline called “comfort women 110” to collect information about the former comfort women. An anonymous tip brought Song, who was living in Miyagi Prefecture, to the world’s attention. After this, the civic groups established a group to support litigation for Korean-Japanese former comfort women and helped Song launch a legal battle demanding an official apology from the Japanese government.

The documentary “My Heart is Not Broken Yet,” directed by Ahn Hae-ryong and released in 2007, covers the slow progress of the lawsuit and the life of Song, the only Korean-Japanese former comfort women to sue the Japanese government. After a legal battle that dragged on for ten years, Song made it all the way to the Supreme Court of Japan, but in the end her lawsuit was rejected. The documentary’s title was inspired by Song’s remark that “Even so, my heart is not broken yet.”

Song’s remark that she may have lost the trial, but her heart was not broken yet served as both a warning that the comfort women issue was not resolved and a message of encouragement to join in the fight. During the documentary, Song condemns war and speaks of universal peace that transcends her own wounds. The film was released in Aug. 2007 and even today continues to be screened in several parts of Japan. People who have seen the film have made comments such as “The world must not make war again” and “We should boldly resist the efforts of the Japanese government to avoid its responsibility.”

During an interview with the Hankyoreh during a visit to Seoul in 2011, Song said that the only thing she thought about while being forced to work as a comfort women, while handing over her baby to someone else, and while being discriminated against and shunned for decades in Japan was that she had to stay alive. “I can’t die until I receive a decent apology from the Japanese. My heart will never be broken by Japan or even by death,” she said.

Song moved to Tokyo because of damage caused by the Great Tohoku Earthquake in 2011, and toward the end she was living in a nursing home. “Song had trouble getting around for the last few years. More recently, she was so weak she could barely speak, so she didn’t have any final words,” said Yang Jing-ja, the president of the litigation support group who took care of Song until recently, during a telephone interview with the Hankyoreh.

By Cho Ki-weon, Tokyo correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 3Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 4Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 5[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 6Inside the law for a special counsel probe over a Korean Marine’s death

- 7[Reporter’s notebook] In Min’s world, she’s the artist — and NewJeans is her art

- 8Japan says it’s not pressuring Naver to sell Line, but Korean insiders say otherwise

- 9[Exclusive] Hanshin University deported 22 Uzbeks in manner that felt like abduction, students say

- 10At heart of West’s handwringing over Chinese ‘overcapacity,’ a battle to lead key future industries