hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

South Korean society grapples with the question of how to respond to Vietnam War atrocities

In May 1999, the Hankyoreh 21 published a shocking report. Titled “South Korea’s Terrifying Troops,” the magazine reported that South Korean forces during the Vietnam War had perpetrated mass sexual assaults and massacres against civilians in various regions south of the southern front in Oct. 1969. It was the first report in the domestic press on civilian massacres by South Korean troops in Vietnam.

Nearly two decades later, the accusations of civilian massacres in Vietnam have been proven to be historical fact, but response measures have been minimal. Meanwhile, attention has been turning to public talks and debates by civil society to uncover the tragic truth and answer the question of what South Koreans can do as citizens of the nation responsible.

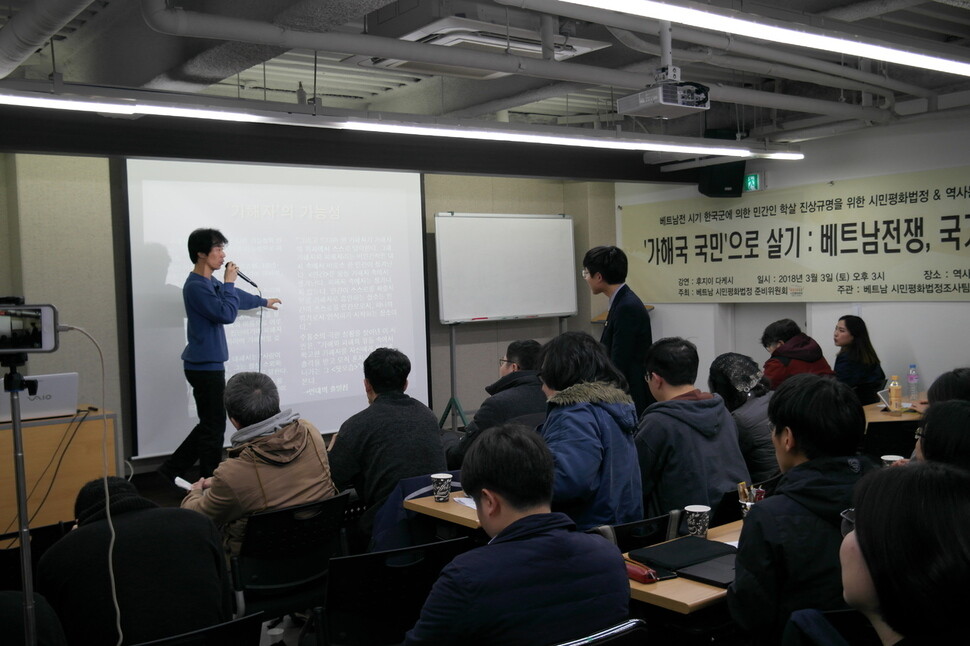

On the afternoon of Mar. 3, over 100 people crowded into the Gwanjiheon auditorium on the fifth floor of the Institute for Korean Historical Studies (IKHS) in Seoul’s Jegi neighborhood. They had come to hear a talk by Takeshi Fujii, a researcher studying South Korea’s contemporary history. The title of the talk was “Living as Citizens of an ‘Aggressor Country’: The Vietnam War, the State, and Us.” The event was organized as part of the lead-up to a weeklong “citizens’ peace court” beginning on Apr. 18 to investigate civilian massacres by South Korean troops during the Vietnam War.

The topic of the Mar. 3 talk, which was jointly organized by IKHS and the citizens’ peace court preparatory committee, remains a sensitive matter both politically and academically. But the citizens attending showed intense interest in the issue. After preliminary applications quickly exceeded capacity, the organizers apologetically decided to broadcast the event live via Facebook.

“An extremely important issue” facing South Korean society

“As someone who is Japanese, I was hesitant about whether I could discuss civilian massacres in Vietnam by Korean troops,” Fujii said. “But after a long period living as an ‘aggressor country citizen’ and a researcher of contemporary South Korean history, I felt the issue was extremely important for South Korean society to change in a positive direction.”

Fujii explained that he had “first become aware of imperial Japan’s history of invading other Asian countries and various human rights issues while taking part in a campaign opposing the imperial system as a university student in Japan in the 1990s.”

“At around 20 years of age, I realized that I was in the position of ‘aggressor’ in every way as someone who was Japanese, male, and non-disabled, and I came to the conclusion that I deserved to die,” he continued, drawing laughter from the audience.

But he went on to say his thoughts “had nothing to do with the victims – I was narrowing my perspective to a personal decision rooted in a strong sense of ethics.”

“Taking responsibility should start not with repudiating ourselves but with solidarity with both aggressors and victims,” he said.

“Because the direct agents of brutal violence in war are made up of individuals mobilized by the state, the use of abstract language about ‘state violence’ results in things becoming a ‘diplomatic issue’ as the victims and aggressors alike lose their specificity and are reduced to certain groups,” he explained.

“This produces an outcome where it falls on the state itself to change relationships formed through violence ordered by that state,” he continued.

The problem does not stop there. As time passes and later generations come to outnumber the original perpetrators and victims, many citizens of the “aggressor country” question why they should assume responsibility for something they didn’t do.

“When you approach things in terms of an ‘aggressors vs. victims’ frame, agents become reduced to structures, which eliminates the potential for real change between the two sides,” Fujii added.

“Only when we cross the boundaries of individual ethical consciousness can we transcend those limitations and move in a positive direction where addressing the legacy of the past becomes a way of producing the future. It is necessary and important to hold states accountable, but we also need self-awareness in terms of what that sort of action produces and why we do it,” he concluded.

While the citizens’ peace court is being organized to document state violence, Fujii’s argument is that when we simply listen to accounts of victimization, we are ignoring the lives of the victims. Instead, he said, we should listen to stories that connect their lives to our lives today.

As an example, workers at Samsung Electronics factories in Vietnam currently work an average of 70 hours a week, and Vietnamese women – with an average age in their twenties – account for over 70% of spouses in South Korean international marriages, with 60.6% marrying within three days of their first meeting. Fujii described the situation as “basically human trafficking.”

In conclusion, Fujii stressed that “the process of addressing the past can be more important than the outcome,” adding that the key questions were what kind of future we can imagine in that process and with whom.

By Cho Il-jun, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 3[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 4‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 5[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 6[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 7[Reportage] On US campuses, student risk arrest as they call for divestment from Israel

- 8Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 9[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 10[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father