hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special feature] Will Korea embrace political refugees from Thailand’s relentless military junta?

At 6:30 am on Jan. 17, 2018, a plane arriving from Bangkok touched down on the runway at Incheon International Airport. Looking through the window, 25-year-old Chanoknan Ruamsap took in a city she was visiting for the first time in her life. When she stepped outside, each breath from her mouth raised a cloud of white mist in the air. It was unfamiliar and cold.

After exiting the airplane, she took her bag and rushed into the restroom. The only things inside the hastily packed bag were a few T-shirts, two pairs of blue jeans, a notebook computer, two books, a university diploma and an ID. There was also a page of information about travel in South Korea, which she had hurriedly printed out just before leaving Bangkok.

Chanoknan locked the stall door and took out the printed page. It contained information on Seoul’s famous cafes and restaurants, as well as Korean Wave stars and K-pop. In her mother tongue, she recited foreign names she had never heard before in her life. She desperately tried to cram the information in – her mind was racing, but she knew that if she could not memorize these things, she would be deported immediately.

She had seen a photograph showing people staying at an airport boarding gate after their refugee application was denied. They had looked like prisoners. If she were sent back home, the only place she could go was prison. Tears began to flow, and she gently tried to hold them back. She also might end up deported if the immigration officer saw her eyes swollen. She could not afford to let any tears show.

She wanted to memorize all the content on the printout, but there wasn’t much time. Staying too long in the restroom might draw suspicions.

Fifteen minutes. That was the time Chanoknan spent studying up on South Korea for the first time in her life. Emerging from the restroom, she steadied her nerves and stood in line for the immigration review. As she waited her turn, she went back over what she had read. She did flinch a bit when she made eye contact with the officer, but she tried to look natural.

South Korea’s immigration offices are notoriously strict with Thai visitors. The reason has to do with the many Thais who come disguised as tourists and secretly seek jobs. The officer looked at Chanoknan’s passport, then her face, then back at her passport. After flipping through the pages a few times, Chanoknan was allowed through without questions. All of the information about South Korea she had crammed into her head quickly dissipated.

But she was unable to let down her guard until she was all the way outside. As she attempted to walk calmly along, she wondered why the officer hadn’t asked her anything. Maybe it was the stamp in her passport. Chanoknan had previous long stays in the US and Japan for her studies. The Office of Immigration may have concluded she was different from the other Thais sneaking into South Korea to work.

As she emerged from the airport doors, a text message arrived from “him.” He told her he would be about an hour late. She had only come to know about the man the previous afternoon. He was the only person Chanoknan knew in South Korea – a friend of a trusted friend.

Only then was she able to turn her head and take in her surroundings. Everything seemed unfamiliar. She was scared. The red dress she had worn from Bangkok did not fit with the drab winter colors around her. Flinching from the cold, she took out a black jacket. It had kept her warm at night in Bangkok, but it was not up to holding off South Korea’s winter winds. She looked at the temperature – close to zero degrees Celsius. It had fallen by 30 degrees over the five hours and 30 minutes she had traveled through the darkness to arrive in the morning.

“Great to see you! Are you okay?” he asked after arriving an hour late. She was far from okay. The tears started to come once again – this time mixed with relief – but she held them back. She did not want to cry in front of a stranger. She followed him onto a bus bound for Gwangju. Once they arrived, he directed her to a guesthouse near a subway station in the city’s center. It was inadequate, but it could pass for cozy. Only then did the tears she had been holding back burst forth. She wept until there were no tears left for her to shed.

112, a number of Thai oppression

At 2 pm on Jan. 16, 2018, Chanoknan was at a post office in downtown Bangkok. Her face turned ashen when she discovered the number “112” on a government notice she received at the post office. In South Korea, “112” is the police hotline that people call when they are attacked or in danger, but in Thailand, that number is a tool of oppression.

Any insult or slander of the royal family – including the king and queen – is considered the crime of lèse-majesté, or in other words defamation of the royal majesty. According to Article 112 of Thailand’s criminal code, an individual convicted of lèse-majesté can be sentenced to up to 15 years in prison.

The moment Chanoknan saw the number, she intuitively felt that today might be her final day in Thailand. Her surging emotions brought her to tears and seemed to make time first race and then crawl.

She had never expected this outcome when she had headed to the post office with a friend, having heard that there was a notice for her. Since she had frequently participated in demonstrations supporting democracy and opposing the junta that currently rules Thailand, she had not been very worried about the notice, which she assumed would be a summons from a military tribunal.

“The angel of democracy” – that was how Chanoknan’s fellow activists referred to her.

A string of unjust arrests

Chanoknan had been an organizer of the student democracy movement since Prayuth Chan-ocha, former commander in chief of the Royal Thai Army, took power in a coup on May 22, 2014. Chanoknan wanted to live in a better society. She wanted to be with people who were changing the world.

During a football game on Feb. 7, 2015, between Thammasat University and Chulalongkorn University, where Chanoknan was studying, she held up a placard that said, “Down with the dictatorship, long live democracy” while chanting slogans. A week later, on Feb. 14, she organized a demonstration in front of the military tribunal in Bangkok to ask the tribunal to stop putting civilians on trial.

Chanoknan attended a total of three peaceful demonstrations and was arrested four times. Most of those demonstrations were part of campaigns opposing the junta and advocating human rights. Each time, she was tried by a military tribunal, not a civil court.

The first time Chanoknan was arrested was on May 22, 2015. On the first anniversary of the coup, she had organized a peaceful protest. The protesters gathered in front of the Bangkok Art and Culture Centre in a flash mob, looking at their watches without screaming any slogans or even saying a word. They simply wanted to remind passersby that a year had passed since Prayuth Chan-ocha had launched the coup.

After about 15 minutes, Chanoknan and the other protesters were rounded up by the police and taken to the police station. The police interrogated her all night long, but she refused to answer their questions. In the morning, they let her go. Demonstrations were held in various parts of Bangkok that day, and a total of 38 people were arrested by the police.

The second time, Chanoknan was arrested by soldiers. On Dec. 7, 2015, she had boarded a train on her way to investigate a corruption case. The junta was accused of meddling in the construction of Royal Park Rajapruek and making off with a huge sum of money. Even though a large number of palm trees planted in the park had not cost a cent, the junta forged documents to make it appear that each tree had cost about US$7,000.

After Chanoknan’s arrest, she was taken to a military base. The military interrogated her but released her without charges. A week after that, she received a summons, which she ignored, assuming she had done nothing wrong. Ten months later, the police arrested her and detained her in the Central Women’s Correctional Institution in Bangkok. When this fact was reported, a fundraiser was launched for her release, and she was immediately let go.

After that, the military and police would visit Chanoknan’s house once a month. She and her family were put under surveillance and frequently interrogated. In 2016, Chanoknan organized a campaign to vote against a constitutional reform promoted by Prayuth’s junta in a national referendum.

On June 24, 2016, Chanoknan was arrested by the police on the way to clean the Constitutional Protection Monument at Laksi Circle, a symbol of the Thai constitution. This was her fourth arrest. When the police searched her car, they found a pamphlet criticizing the corruption of the current government.

Politically targeted for having shared a BBC article two years ago

While Chanoknan had always remained resolute despite her multiple arrests, the notice she received at the post office was different. She realized that something had gone wrong. The reason given for her indictment was that she had defamed the royal family by sharing a BBC article on Facebook on Dec. 3, 2016. The article had discussed a number of allegations about the current king Vajiralongkorn, also known as Rama X, including philandering, gambling, his extravagant lifestyle and his involvement in illegal businesses.

Chanoknan’s fellow activist and longtime friend Jatuphat Boonpattaraksa had been arrested by the police in 2017 on the same charge of lèse-majesté. Jatuphat was sentenced to two years and six months in prison by a high court in Aug. 2017 and is currently serving his sentence at Khon Kaen Prison. On May 18, 2017, South Korea’s May 18 Memorial Foundation awarded Jatuphat its Gwangju Human Rights Prize.

Chanoknan thought the charge against her was unfair. Two years had already passed since she shared the article. Even though 2,600 people had shared the article at the time, the only people targeted by the junta were Jatuphat and Chanoknan. Obviously, this was because they were democracy activists who were resisting the junta. But resistance was impossible.

When The Hankyoreh spoke with Chanoknan’s friends, they all said she had been the bravest democracy activist of all. “Chanoknan had the clearest certainty even among the other activists. Before going to a demonstration, she would encourage the others not to be afraid of getting arrested,” one friend recalled.

Even so, Chanoknan was afraid of the charge of lèse-majesté. She was seized by a fear unlike anything provoked by the junta’s oppression until that point. She had heard about people who had been sentenced to 100 years in prison for lèse-majesté. There were people who had died in prison, people whose lives had been cut short in brutal and inexplicable ways. She did not want to end up like them.

On her way home from the post office, Chanoknan contacted the president of the Poverty Council, a group she belongs to. The president put her in touch with a human rights attorney in Bangkok. Before long, the fact of Chanoknan’s indictment had spread through activist circles. She continued to get phone calls from her associates at the New Democracy Movement, the organization of which she was the cofounder and spokesperson.

From upper middle class to political activist

Upon arriving at home, Chanoknan told her parents, who were devastated by what had happened to their beloved daughter.

Chanoknan had been born in an upper middle class family and lacked for nothing while growing up. And so when she first attended a demonstration in 2005, she was on the side of the “yellow shirts” – a pro-establishment group, largely consisting of the middle class and the elites, who opposed former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra for his corruption and demanded his resignation in 2006.

Yellow is the color that represents the monarchy in Thailand. On the other side of the political divide were the “red shirts,” whose ranks were mostly filled with farmers and the urban poor.

But after Chanoknan spent her junior year of high school as an exchange student in Ohio, she began to view her life in Thailand from a different perspective. She rebelled against her parents, who are devout Buddhists, by announcing that she does not have a religion.

Thanks to her bright mind and outstanding grades, Chanoknan gained admission to Chulalongkorn University, considered the country’s top university, where she majored in political science. This would have guaranteed her a respectable position in society, if only she had meekly focused on her studies instead of resisting the junta. But Chanoknan joined the democracy movement as a student activist and ultimately was charged with lèse-majesté. Upon hearing this news, her heartbroken father let out a sigh and poured himself one drink after another.

Chanoknan’s friends told her she needed to get out of Thailand. At 4 pm, just two hours after receiving the notice from the government, she made up her mind to leave. She pulled out her suitcase and packed her things. She didn’t even have time to say goodbye to her younger sibling, who was attending a university in the countryside and staying at the dormitory there.

One human rights organization offered to help Chanoknan. If she was to depart immediately, they told her, she did not have many options. They recommended South Korea, where the UN human rights organization, called the UNHCR, has a presence. Some other options were the Philippines and Hong Kong, but those countries only allowed a visa-free sojourn of 15 days. In South Korea, on the other hand, she could stay as long as 90 days without a visa.

Chanoknan decided to finalize her plans during three months in South Korea. After that, she meant to travel to a country where it would be easier to communicate in English. She wanted to go to a European country like Germany or France. There were already many Thai people living in those countries who had applied for refugee status for political reasons. She figured that South Korea would just be a temporary stopover on the way there.

Chanoknan’s mother drove her to Suvarnabhumi Airport, with three of her friends. Chanoknan asked her mother not to get out of the car, concerned her mother might suffer unpleasant consequences if they were caught together on the airport’s security cameras. Her mother handed her 50,000 baht, worth about US$1,600, that she had managed to throw together. One of the three friends who had come to the airport lobby to see her off began to cry, and soon all four were weeping the tears they had been holding back. Chanoknan wiped her eyes and tried to calm down. She used an electronic kiosk to pass through airport immigration, hoping to avoid human contact as much as possible.

Even after boarding the airplane, Chanoknan could not let herself cry. If someone asked her what was wrong, there was no explanation she could give. An in-flight meal was served, but she didn’t touch it. In a daze, she thought about the past. She tried to think of what to do next, but she had no ideas.

In Gwangju, Chanoknan’s contact visited her every day, taking her to various parts of the city and introducing her to people at human rights organizations and other groups. She was put in touch with a pro-bono human rights lawyer to help her with her refugee application. The May 18 Memorial Foundation told her it would cover her living expenses until she gained approval as a refugee.

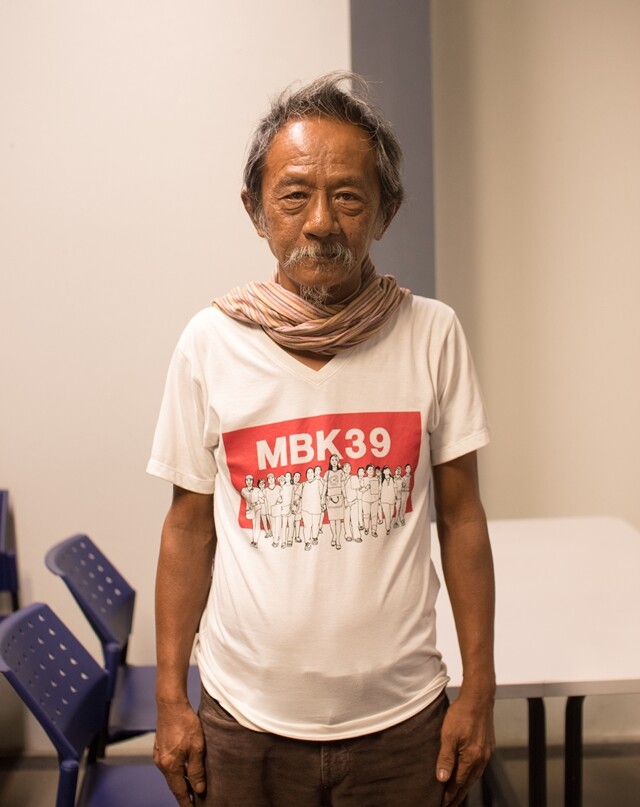

[%%IMAGE5%%]Stuck in limbo

At the end of March, Chanoknan made up her mind to apply for refugee status in South Korea and submitted her documents. Such an application can take as long as five years, if the case goes all the way to the Supreme Court. The problem is her status in society during that time. Until she is recognized as a refugee, there are numerous obstacles to getting work or going to school to learn Korean. In her interview with The Hankyoreh, Chanoknan expressed her intense anxiety: “I’m not a refugee, I’m not a Korean, and I’m not a tourist from Thailand. I’m not anything here.”

In April, Chanoknan attended a seminar about South Korea’s refugee policy at the Gwangju International Center and learned to her dismay that the country has a low refugee acceptance rate. If her refugee application is not accepted, she will have to leave South Korea, leaving her in limbo as she bounces from country to country.

To be sure, Chanoknan’s ultimate destination is not South Korea, where she would at best be a refugee, but her home of Thailand. For the moment, however, she does not expect to be going back home anytime soon. “The collusion between the monarchy and the junta is really bad and is unlikely to be resolved any time soon. Thais aren’t used to questioning the system and wrestling with its problems,” she said.

“At the moment, Thailand is not a democratic republic. Just look at the political refugees scattered around the world and the prisoners of conscience who are locked up in prison. Even so, I want to support the Thai people and bring them the courage to achieve democracy and human rights through their own strength.” Even if she is accepted as a refugee in South Korea, Chanoknan says, she intends to look for something she can do for Thai democracy.

When Chanoknan mentioned that she plans to visit Seoul in June, I asked her what she hopes to do there. “I’d like to go to the slums of Seoul and meet the homeless,” she said, her eyes sparkling.

By Lee Jae-ho, Hankyoreh 21 staff reporter from Gwangju and Bangkok

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Original Korean :http://h21.hani.co.kr/arti/cover/cover_general/45401.html

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/8317138574257878.jpg) [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father![[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms? [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/3617138579390322.jpg) [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 2[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 3New AI-based translation tools make their way into everyday life in Korea

- 4Opposition calls Yoon’s chief of staff appointment a ‘slap in the face’

- 5Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan

- 6Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 7[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 8Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76

- 9[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 10[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady