hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Remembering Bae Bong-gi, the first comfort woman to testify about her experiences as sex slave

Bae Bong-gi – readers may not be familiar with the name, but she was the first woman to testify about her experience as a sex slave, or comfort woman, for the imperial Japanese military. In November 1944, at the age of 30, Bae left her home and went to Tokashiki, a small island in Okinawa Prefecture, where she became a comfort woman. She lived under the pseudonym of Akiko in a comfort station for the Japanese army that was called the “house with the red-tiled roof.”

Not long afterward, Japan was defeated by the US in the War in the Pacific. After the Japanese left, US troops came to the island. In a concentration camp run by the US troops, Bae had to keep doing the same work. Korea had been liberated, but she wasn’t able to go home.

Bae’s body and spirit were broken on that distant island. Without a home of her own, she stayed in a tiny shed, without any gas or running water. As she suffered a nervous breakdown in her shed, she would scream from her headaches and neuralgia. Children in the neighborhood called her the “crazy old woman.”

In May 1972, the Japanese government regained sovereignty of Okinawa, which had remained under the control of the US after World War II. At that point, Bae had to make a tough decision. Japan had announced that it would only be granting special permanent residency to Koreans living in Okinawa Prefecture who could prove they had entered Japan before Aug. 15, 1945.

In order to avoid being deported from Okinawa, Bae had to confess that she had once been a comfort woman. “I lived in Okinawa as a comfort woman,” Bae said to the owner of a restaurant she’d used to work for. In October 1971, the Japanese press covered the story of Bae, who was 51 years old at the time. Thus, Bae was forced by the Japanese government and press to reveal her past.

Bae cried when she thought of her home. In September 1988, reporters from a Japanese women’s weekly called Josei Jishin interviewed Bae, who was 74 years old at the time. The reporters said they would pay her way if she wanted to visit Korea. “You know, I’d like to go, I really ought to go sometime,” Bae said and then sobbed for quite some time.

Oct. 18, 1991, three years later, was an unseasonably hot day in Okinawa. That was the day when Bae passed away, without ever managing to return to Korea, at the age of 77.

“In my dreams, I went to my hometown, but I didn’t have a home. [. . .] I never had a house, you see. [. . .] In another dream, I couldn’t go into my house, because I didn’t have one. [. . ] Even so, I often went back in my dreams,” Bae testified in “House with the Red-Tiled Roof,” written by Fumiko Kawada

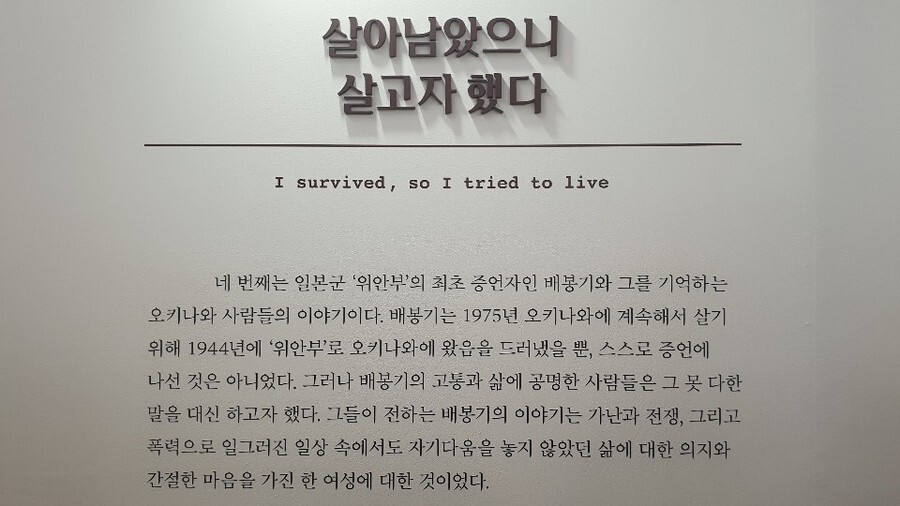

While Koreans only vaguely remember Bae, Okinawans remember her clearly. On Mar. 16, Hong Yun-sin, a special researcher at the Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies at Waseda University, delivered a lecture to complement an exhibit titled, “Records, Memory, the ‘Comfort Women’ of Okinawa and the Story of Bae Bong-gi” at the Seoul Center for Architecture and Urbanism.

Hong has been collecting records and public documents related to comfort stations in various parts of Okinawa and cross-checking those with local testimonies. The scholar published a book in Japanese in 2016 called “Comfort Stations and Memories of the War in Okinawa,” which is currently being translated into Korean. During the course of the two-hour lecture, Hong raised difficult questions about how Okinawans remember Bae and the other comfort women, how those memories are related to the Okinawa peace movement and how Koreans ought to remember the comfort women.

In 1992, a group that is researching the history of women in Okinawa put points on a map of the prefecture to indicate the location of some 130 comfort stations. “We were protesting the presence of so many comfort stations on Okinawa. We don’t have any legal evidence, but this is an unshakeable fact,” Hong said during the lecture.

Okinawans victimized by Pacific War as much as the comfort women were

The comfort women and the people of Okinawa were all victims of the same war. One-third of the people in the prefecture were killed during the War in the Pacific. “The Okinawans were unable to forget the comfort women who took care of them during the war. Their own experience includes the experiences of the comfort women. By speaking of their own experiences, they were able to express how hard things were for the comfort women. While they hadn’t seen Bae themselves, they talked about their experiences with the comfort stations, places where women like Bae were taken. We need to focus on the ‘warm-hearted gaze’ with which they protected women.”

An article by the Hankyoreh titled “Bae Bong-gi: First Witness of the Comfort Women, Forgotten by Koreans,” published Aug. 8, 2015, was also quoted in the lecture. When Gil Yun-hyung, the Hankyoreh’s correspondent in Tokyo at the time, became the first Korean reporter to write a story about Bae, he had to face the guarded, even indignant gaze of the old women of Okinawa.

“That gaze could actually be the warm-hearted gaze of people who wanted to protect the comfort women. You’ll remember how I told you that points were marked on the map to indicate the comfort stations. The comfort stations in Okinawa were privately owned houses. Even after the war was over, Okinawans kept living in those houses. They testified that the places they’d lived in had been used as comfort stations. They were memorial spaces intended to inform people about the painful things that had happened there. These are the experiences that Bae concealed and the Okinawans disclosed. This isn’t a confession; it’s a revelation that they were the ones who protected the victims and witnessed the comfort women,” Hong said.

Bae’s experiences has significant implications for S. Korea’s #MeToo movement

The fact that Bae had to come forward with her suffering as a comfort woman in order to survive has significant implications for the #MeToo movement in Korean society. “What kind of knowledge can we gain from the fact that she was unable to talk about her pain? [. . .] There are many people who have suffered but cannot join the #MeToo movement. There are people who’ve chosen #WithYou, to stand with them. What kind of knowledge can we gain from the fact that they aren’t able to talk about their pain? That’s a question we need to ponder.”

The Okinawans who survived the War in the Pacific have chosen to stand with the former comfort women by testifying that their own homes were used as comfort stations. That’s their unique way of remembering the comfort women. “The comfort women survived. They used their testimony to tell others about their experience during the war. While meeting with various people, they’ve turned into human rights activists and unparalleled feminist thinkers. But we need to be aware of the potential violence in our attitude [of demanding a consistent testimony]. There’s also a tendency to start judging their testimonies, asking whether it might be false and whether it might have changed over time. We also have to embrace the contradictory testimonies of the comfort women.”

South Korean society has long been indebted to the comfort women for their testimony. It has demanded that they testify again and again. The Okinawans were different. On the island of Miyako, in the southern part of the prefecture, a stone was erected in memory of the comfort women. The locals remembered how the comfort women had once rested on a certain stone on their way to and from the laundry washing place, and they moved that stone to the site of the memorial.

The stone is indelibly engraved with the following message, colored in white, in twelve languages, including Korean: “We share the pain of all the victims of sexual violence by the Japanese military and long for an end to sexual violence resulting from armed conflict occurring around the world and for the advent of a peaceful world in which war will never again occur. KOREA.”

By Lee Jeong-gyu, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 346% of cases of violence against women in Korea perpetrated by intimate partner, study finds

- 4Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 5‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 6[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 7Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 8Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 9“Parental care contracts” increasingly common in South Korea

- 10[Interview] Dear Korean men, It’s OK to admit you’re not always strong