hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Reportage] Life of Joseon exile rediscovered in France 100 years later

“Bonsoir, Madame. Oui, Mademoiselle. Oui, Mademoiselle.”

Even as he repeated the words, they sounded unfamiliar. He felt seasick from the long journey. The young man turned his gaze to the expanse of the ocean. It was November, a time when the cold would begin arriving in his hometown, but on the Indian Ocean it was as sweltering as the early summer days of June. For a brief moment, 22-year-old Lee Yong-je felt his heart beat faster at the thought that he had escaped Korea, where the old ways of Joseon and the tyranny of Japan held sway, and arrived here on a foreign ocean. It was the year after 1919, when the March 1 Independence Movement had taken place. The young man had no idea at the time that it was a journey he would never return from.

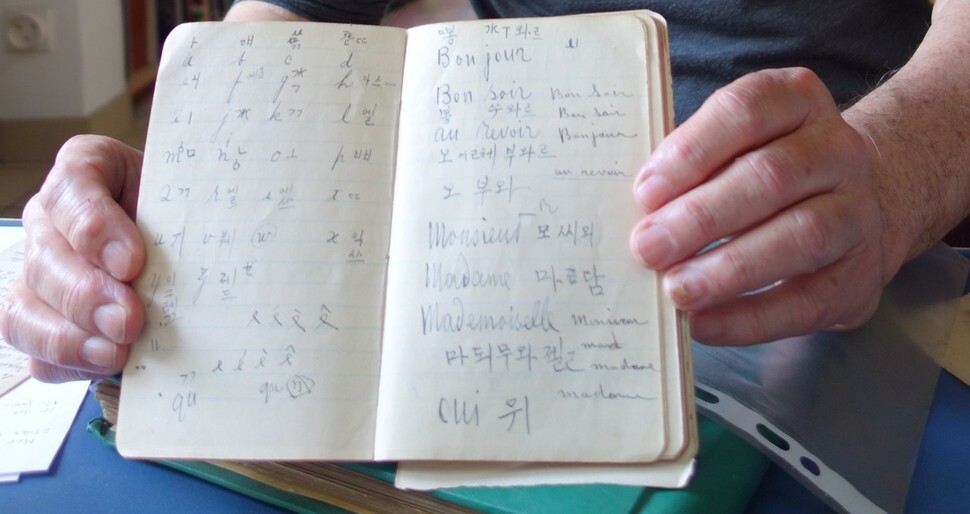

Meeting the Hankyoreh on Apr. 18 in the commune of Bourg-la-Reine on the outskirts of Paris, his son Antoine, 73, smiled as he showed his father’s notebook and its labored French script from 99 years earlier.

“This was my father’s initial French proficiency,” he explained. With his silver hair and shaggy gray beard, Antoine looked like an ordinary Frenchman, but he bore the Korean surname of “Lee.” After arriving in France in 1920, Lee Yong-je married Frenchwoman Madeleine Koechlin in 1936. The two would go on to have three sons, including Antoine, and three daughters.

Antoine did not know much about his father’s life when he was growing up. “My father did talk sometimes about his great-uncle who raised him, and his own father who was a logger in Siberia,” he said. “But the sequence of events was so mixed up that I couldn’t understand it.”

It was only after Lee Yong-je’s death in 1986 that his family gained a fuller understanding. That was when they received a copy of a 1983 interview conducted with him for research purposes by Korean studies scholar Alexandre Guillemoz of the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (EHESS). The life described in the interviews was a harsh one. Most of all, Lee carried more stories inside of him than his children remembered.

The name Lee went by in France was “Li Long-chi,” a Chinese pronunciation of his Korean name. Born in 1898, he would live 66 years of his life in France, but his passport showed him retaining Taiwanese citizenship up until his death in 1986. He was effectively stateless. He had been to the People’s Republic of China, but did not know much about Taiwan. Lee did have a hometown, a place where he had been born and raised. It was in the northeast Korean city of Hamhung, where the plains were painted golden in the fall with ginkgo foliage and dropping stalks of rice.

His story began with the March 1 Independence Movement in 1919. In the early period of the movement, it was younger people who stood at the vanguard, fueling it from the front lines of the demonstrations. It was also younger people whom the imperial Japanese forces targeted with their swords. Soon after the March 1 Movement, large numbers of young people began leaving Korea, either to evade Japanese capture or to commit themselves to the independence movement abroad. For Lee as well, the March 1 Independence Movement was the impetus behind his departure. Working as a clerk in his hometown, he found himself under Japanese surveillance after passing one of his juniors a copy of the Korean Declaration of Independence he had received from a friend. The junior was thrown in prison when the declaration was discovered. Lee had been looking for opportunities to leave Korea, and his friend made an unexpected proposal.

“Let’s go to France,” the friend said. “If we can get as far as Shanghai, there’s supposed to be an organization that will take us to France.”

At the time, China and France had a “Frugal Study Association” program in place, a financial aid system that allowed Chinese students to work while they studied at French schools. Both Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping would travel to France through the system in 1920. Sensing an acute need for capable diplomats, the Republic of Korea Provisional Government actively committed participants in the program from among the young Koreans flocking to Shanghai. In addition to Lee Yong-je, the list of passengers bearing Chinese passports on the French ship Porthos on Nov. 7, 1920, including future Acting President Ho Chong, future Yonsei University Professor Jeong seok-hae, future Minister of Culture and Education Kim Beop-rin, and Seo Young-hae, who would later serve as the Korean Provisional Government’s correspondent in France.

Surviving in Paris was difficult for Lee. He struggled to continue his studies while working odd jobs as a steelyard worker, brick factory laborer, and hospital handyman. It was a very different life from that of Seo, who attended school north of Paris in Beauvais as soon as he arrived in France and later committed himself to campaigning for Korean independence within the country. It was also different from his colleagues who would return home to become government officials or professors after completing their studies. Lee continued to exchange letters with his family back home in Hamhung, Hamgyong Province, but he would never again set foot on the Korean Peninsula.

“I think he did have hopes of returning home after liberation in 1945,” Antoine said. “But my father quickly abandoned them – because of Korea’s division.” Neither the area south of the 38th Parallel nor the one to the north was the homeland that Lee yearned for. During the Rhee Syng-man administration, South Korean Ambassador to France Kong Jin-hang promised to issue him a South Korean passport, to which Lee reportedly replied, “As long as Korea remains divided in two, I will not take a South Korean or a North Korean passport.”

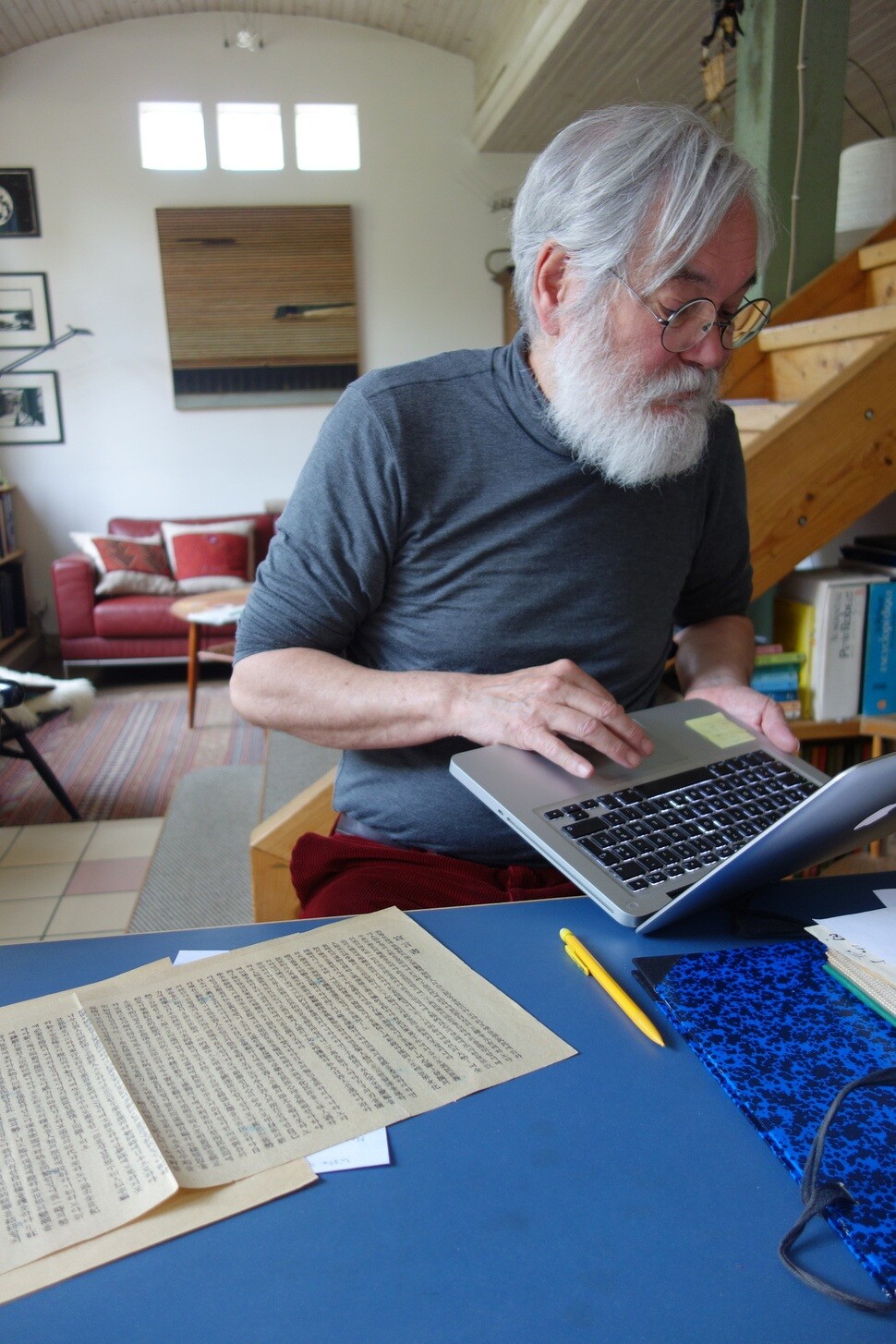

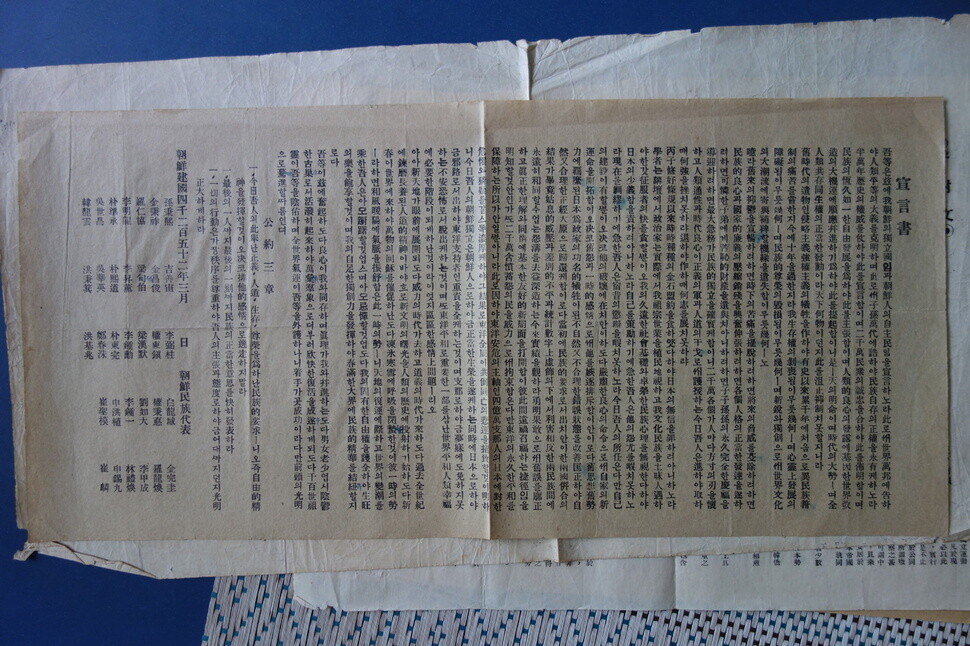

A look at the personal effects left behind by Lee suggests his desire for Korea’s independence and peace ran deeper than anyone’s. Among the remaining old items painstakingly kept by Antoine from his father are statements from the independence movement that have been preserved without so much as a speck of mold – including a statement issued by the Korean Independence Party at the time of Lee Bong-chang’s attempted assassination of Japanese Emperor Hirohito in Tokyo in 1932.

Antoine had no way of knowing when some of the documents were written or what they were about. One of them was an independence declaration made by 33 national representatives on Mar. 1, 1919. Park Chan-seung, a Hanyang University professor and longtime researcher of the March 1 Independence movement, told the Hankyoreh the document was “pretty similar to the ‘original copy’ printed by the Cheondogyo publishers Boseong, but the script and the punctuation are different.”

“The print hasn’t been reported yet in South Korea, so it looks like we will need to examine it a bit more,” he said.

Antoine’s father never explained the documents to him. Despite being a linguist who extensively studied Korean, Lee never taught his children to read the language. Only after his father died and his own hair had begun to go gray did Antoine start learning about his father and his homeland. Only later on did he learn why his father had such an affection for ginkgo trees, which are relatively rare in France – to a man living an uprooted life for nearly 70 years, the gold of the ginkgoes was his only means of recalling the landscape of his home. Antoine planted one ginkgo each in the backyard of his home and the garden of his Normandy villa, where he also laid the remains of his father to rest.

“More than anything, I think my father longed for the vistas and trees of his home. Sadly, he had no hope of returning to a unified homeland.”

The colonial Joseon occupied by Japan that Lee and other disgusted young men like him left behind no longer exists. But 100 years later, there is still no “peaceful” homeland for a soul weary from life in exile to return home to and rest comfortably in.

By Um Ji-won, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 3[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 4After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 5[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 6Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 7US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 8All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 9[Photo] Smile ambassador, you’re on camera

- 10[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda