hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special report- Part VII] Countries around world change trade policies to fight international labor violations

International standards about how companies are handling human rights are changing. The leaders of the G20 countries recently released a declaration about a “sustainable global supply chain,” while there’s a campaign in European countries such as France and Finland to pass laws that would require companies to guarantee comprehensive labor rights in overseas production facilities. Such countries intend to aggressively intervene in multinational firms’ transnational exploitation of workers. For Samsung’s global business model to be sustainable, experts say, a major transformation is needed — retooling systems and bringing attitudes throughout the organization in line with the international focus on bolstering human rights and labor rights at corporations.

Transforming corporate standards for human rights

At the beginning of June, the government of Finland officially announced legislation that would require corporations to conduct “human rights due diligence [HRDD].” According to the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre, Finland will soon begin canvassing the opinions of stakeholders prior to passing the law in question. The Finnish government has also promised to spearhead human rights due diligence legislation at the level of the European Union (EU). Finland takes over its duties as chair of the EU this month.

Human rights due diligence is a concept invented by the UN in 2011 to tackle the issue of multinational firms amassing immense wealth by exploiting workers in underdeveloped countries with lax labor regulations and cheap labor, setting up operations that force workers to work for long hours for low wages. While announcing the corporate principles for protecting human rights, the UN asked multinational companies like Samsung Electronics that manufacture products with parts acquired from around the world and then export those products back to those countries to be accountable for ensuring a higher level of human rights through their business management. This principle states that each company has full responsibility to identify and prevent human rights and labor rights infringements that occur in their global supply chain.

After the UN declared that companies are responsible for exercising human rights due diligence, several countries in Europe began taking steps to apply this principle to their domestic law. The first was France, which passed a law in early 2017 that required all French-based conglomerates with more than 5,000 employees to perform human rights due diligence and to submit their related plans. Consequently, these companies are required to report violations of labor rights and environmental regulations not only at their headquarters in France but also at factories around the world, and to draft plans for dealing with such violations. If the Finnish government implements this law after the canvassing period, it will become the second country, after France, to make human rights due diligence a legal requirement.

“The spread of human rights due diligence legislation through France and other countries of Europe means that human rights-oriented management is moving into the sphere of law-abiding business management. In the future, the question of whether multinational companies are violating human rights in less-developed countries will be an important factor in making their reputation and determining whether consumers and investors trust them,” said Gwak Eun-bi, an attorney with the law firm Jipyong who wrote the report, “The Institutionalization of Human Rights-Sensitive Business Management in France.” Gwak explains that Samsung and other companies based in South Korea will have no choice but to understand and to accept such movements.

Labor rights appeared in a declaration by G20 leaders

Another notable change is that the leaders of the G20 countries adopted a declaration about sustainable global supply chains in August 2017. During a meeting in Hamburg, Germany, the leaders made the following pledge: “In order to achieve sustainable and inclusive supply chains, we commit to fostering the implementation of labor, social, and environmental standards and human rights in line with internationally recognized frameworks, such as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy.”

“We will work towards establishing adequate policy frameworks about human rights-oriented management in our countries such as national action plans on business and human rights and underline the responsibility of businesses to exercise due diligence,” the leaders also said in this declaration. This was an unprecedented example of these 20 countries devising their own solution for tackling labor and human rights violations in multinational firms’ global supply chains.

The UK’s Modern Slavery Act, which was passed in 2015, is also considered a legal step toward requiring human rights due diligence. The act makes it mandatory for companies doing business in the UK to report that they aren’t engaging in human trafficking, using child labor to manufacture products, or trading in such products. The British branch of Samsung Electronics submitted one such report in 2017. This past May, the parliament of the Netherlands passed a law that requires companies to perform human rights due diligence in regard to child labor. And in February, the German press reported the first draft of a law prepared by the Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) that would make human rights due diligence mandatory.

Criticism about “medieval labor conditions”

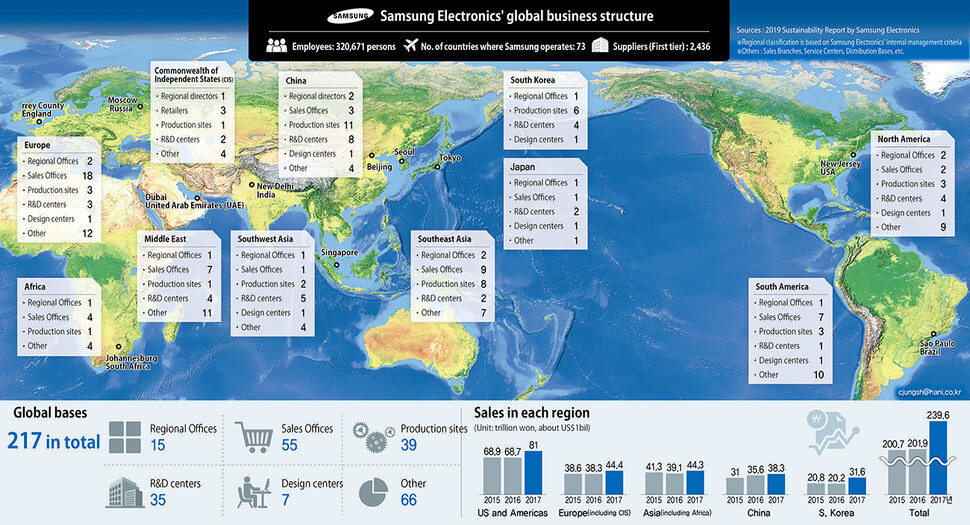

The international community’s increasing demands for multinational firms to pay more attention to how their business affects human rights is connected to Samsung Electronics’ management practices in the various countries of Asia. Although the poor working conditions at the company’s domestic and international factories hadn’t received much coverage in South Korea until the Hankyoreh’s series of articles titled, “Global Samsung: a report on sustainable labor practices,” this issue had already stirred up considerable controversy abroad. As of the end of 2017, Samsung Electronics had 217 business organizations in 73 countries around the world. These organizations include 39 production corporations in Asia, Europe, Central America, and South America.

In May 2016, the International Trade Union Confederation (ITCU), the world’s largest coalition of labor unions, launched its “End Corporate Greed” campaign, which sought to hold multinational firms responsible for union busting, low wages, and excessively intense labor. The first company targeted by this campaign was Samsung. In a report titled, “Samsung: Modern Tech, Medieval Conditions,” that was printed that October, the ITCU drew attention to the long work hours at Samsung Electronics’ factories in China, its suppression of unions in Indonesia, and its indiscriminate use of probationary workers in India. The ITCU argued in the report that Samsung’s policy of no tolerance for labor unions had affected the entire electronics industry in Asia.

Sharan Burrow, who led the composition of the report as the ITCU’s general secretary, sent an open letter to South Korean President Moon Jae-in in March 2018, shortly before Moon was scheduled to visit Vietnam for a summit there. In her letter, Burrow brought up the issue of worker safety at Samsung Electronics’ factories in Vietnam and voiced the ITCU’S serious concerns about human rights and labor rights at the company’s factories in Vietnam. Burrow asked the South Korean government to take action to resolve the problems at Samsung’s factories.

A report called “Labor Conditions at Foreign Electronics Manufacturing Companies in Brazil” that was released in December 2017 by an NGO called the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) devoted considerable space to the controversy about long work hours and human rights violations at Samsung Electronics’ factories in that country. Other NGOs that contributed to this report were Good Electronics Network, a European watchdog group for the electronics industry, and Repórter Brasil, a Brazilian labor group. In a report called “Flex Syndrome” published in December 2012, SOMO addressed labor conditions at a Samsung Electronics factory in Jászfényszaru, Hungary.

“The situation is changing now”

“Prior to this, huge companies with global supply chains such as Samsung regarded the workers in each country as being disposable goods. That happened because the legal systems in those countries, the systems that are supposed to monitor and supervise these companies, were not in line with global standards. But what we should focus on is the fact that the situation is changing now,” Sharan Burrow said in a written interview with the Hankyoreh on July 24.

The labor environment in some countries in Asia, Central America, South America, and Eastern Europe is relatively poor. In some cases, labor laws aren’t up to international standards; in other cases, the laws exist, but aren’t enforced properly because of local customs. Low wages and business-friendly legal arrangements are bound to be attractive for multinational firms.

In 2001, for example, Samsung Electronics built a new mobile phone factory in Tianjin, China. One of the advantages of this location was that it gave Samsung direct access to the Chinese market, but an even bigger factor was the cheap wages there. With a yearly production capacity of 100 million phones, the Tianjin factory served as the company’s largest production facility through the early and mid-2010s.

The prestige of the Tianjin factory underwent rapid decline because of accusations about poor labor conditions in 2012, as well as increasing labor costs. After Samsung Electronics built mobile phone factories in Vietnam (at Bac Ninh in 2008 and at Thai Nguyen in 2014), the output of its Tianjin factory fell even further. In December 2018, Samsung finally announced it was shutting down its Tianjin plant. The average wage of workers in Vietnam is reportedly less than half that of Chinese workers.

The Samsung Electronics factory in Noida, India — which will be the world’s largest single smartphone manufacturing facility when construction wraps up next year — can be seen as part of the same pattern as the shift to Vietnam. Such relocations clearly illustrate how capital tends to gravitate toward countries that are lax in their overall management of labor conditions, including not only the level of wages but regulations on labor intensity, work hours, and chemicals. The result is that Samsung has gotten a nasty reputation: wherever it sets up shop, it sets a new global low.

Samsung has recruited experts on international labor rights, but more needs to be done

Samsung Electronics is aware of the international community’s demands for multinational companies to adopt business practices that are sensitive to human rights. This past March, the South Korean press widely reported that Samsung had become the first South Korean company to create a director for foreign labor and human rights, recruiting Linda Kromjong, former secretary general of the International Organization of Employers, for that position. This appointment was taken to mean that Samsung means to raise its corporate social responsibility for labor and human rights to a global level.

Samsung has furthermore provided a detailed account of its labor and human rights standards and its implementation of those standards in its yearly sustainable management report. The company also stresses that it thoroughly abides by the code of conduct of the Responsible Business Alliance (RBA), formerly called the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition (EICC), of which it’s a member. Samsung has also made a point of commissioning teams of experts to assess workplaces that are identified as being particularly dangerous in terms of labor and human rights. One caveat is that the global labor and human rights experts on these teams are selected by Samsung itself.

“Given the increasing interest worldwide about human rights due diligence, consumers in Europe, at least, are now going to be asking whether Samsung products are being manufactured in factories where labor rights are fully respected, and whether workers are being exploited in the production process. Samsung’s sustainability will depend not on whether it recruits labor and human rights experts, but on how determined it is to adopt a business approach that respects human rights,” said Na Hyeon-pil, secretary-general of the Korean House for International Solidarity.

By Choi Seong-jin, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/8317138574257878.jpg) [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father![[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms? [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/3617138579390322.jpg) [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 2[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 3Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 4Opposition calls Yoon’s chief of staff appointment a ‘slap in the face’

- 5Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan

- 6Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76

- 7New AI-based translation tools make their way into everyday life in Korea

- 8[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 9[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 10[Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue