hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

A Japanese-American filmmaker’s quest to shed light on the comfort women issue

“Where is the main battleground of the cold war that’s being fought over the comfort women issue?”

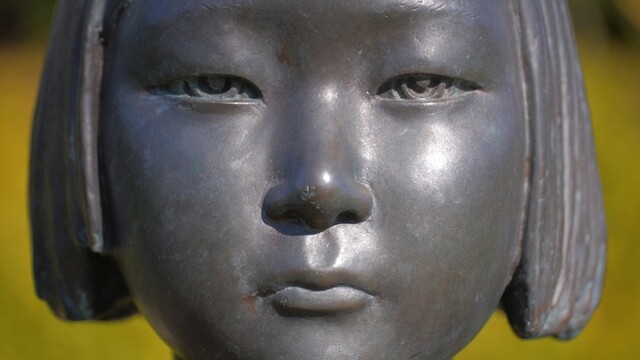

The documentary, “Shusenjo: The Main Battleground of the Comfort Women Issue,” which is being released in South Korean theaters on July 25, plots a different course from previous films that have dealt with the comfort women issue. During the making of this film, director Miki Dezaki, a 36-year-old Japanese-American, interviewed not only professors and groups who support the comfort women’s cause but also 30 or so far-right Japanese historical revisionists who deny their very existence. By bouncing their conflicting arguments off each other, Dezaki offers a new perspective on the comfort women issue. As the very title implies, the contestants in this logical battle — which is fierce enough to evoke an actual battleground — continue to trade blows.

South Korea’s Liberation Day, Aug. 15, is just around the corner, and anti-Japanese sentiment is running high because of punitive economic measures recently taken by the Japanese government, led by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, in retaliation for the South Korean Supreme Court’s decision awarding compensation to Koreans forced to provide labor to Japanese companies during the colonial occupation. Since the documentary is being released as such a time, it will be interesting to see what kind of response it evokes from South Korean viewers.

When Dezaki arrived in South Korea on July 15, he had several quips at the ready. “I’ve got to tip my hat to Abe for making an issue that’s boosted interest in my film. Saying that I didn’t want Abe to watch the film has also been helpful in promoting it,” the filmmaker said with a laugh.

Dezaki offered the following account of how he’d come to make the film. “I’d realized that there’s a serious gap in information about the comfort women issue between South Korea and Japan and that that gap sometimes leads to conflict. I felt that there was a need for a documentary that could give a clear comparison of the points being debated.”

As this suggests, Dezaki chose not to have the elderly victims of the comfort women system take the stand to criticize historical distortions. Instead, he meticulously tracks down and dissects the documents and press reports that Japan’s far-right figures cite as evidence. Along the way, the film treads upon some very sensitive issues, such as the truth of claims that the comfort women were forcibly abducted, detained, and forced to become sex slaves and the accuracy of the estimate that there were 200,000 comfort women.

“The main documents by US army units that reported on the comfort women show that they were just prostitutes and that they were paid rather well for their work.” “Why do so many people take such an excessive interest in this dumb issue? It must have some kind of pornographic appeal for them.” Insensitive remarks spouted off by Japan’s right-wing figures are refuted by the director with sparkling logic, his targets including Yoshiko Sakurai, one of Japan’s leading right-wing pundits; Mio Sugita, a lawmaker with the Liberal Democratic Party; Kent Gilbert, a pro-Japanese American lawyer; and Hideaki Kase, a member of Nippon Kaigi (Japan Conference), Japan’s biggest right-wing group.

Born into a family of Japanese immigrants to the US, Dezaki spent five years working as an English teacher in Japan, starting in 2007. After posting a video to YouTube about racism and discrimination in Japan, he came under attack from the right wing. That was when he learned that Takashi Uemura, a former reporter for the Asahi Shimbun newspaper who was the first to cover the comfort women issue, had faced similar attacks. “Why is the Japanese right wing so sensitive about the comfort women issue?” Dezaki asks at the beginning of the film. That question is a thread running throughout the entire film.

The state can “never be wrong and should never apologize”

Japanese intellectuals in the documentary, such as professors Koichi Nakano and Setsu Kobayashi, say that the Japanese right wing’s ideological conviction that “the state can never be wrong and should never apologize” is “based in a deep-rooted desire to return to the pre-war Meiji constitution and their Shinto faith, which centers on the emperor and involves visits to the Yasukuni Shrine, where the spirit tablets of class A war criminals are still worshipped as divine.” At the heart of this is the Nippon Kaigi, the hotbed of Japan’s far right wing, with 85% of Japan’s cabinet belonging to the Nippon Kaigi group in the Japanese Diet. When we recall that Abe’s maternal grandfather was Nobusuke Kishi, a Class-A war criminal and a member of the cabinet of Prime Minister Hideki Tojo, who ordered the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the historical outlines of Japan’s right wing become clear.

These groups have also flexed their muscles on the textbook issue. All middle school textbooks in Japan dealt with the comfort women issue in 1997, after the Japanese government issued the Kono Statement in 1993, acknowledging its responsibility for the Japanese imperial army’s involvement in the comfort women system. But by 2012, all mention of the comfort women had been erased from textbooks. That was the result of efforts by the Japanese Society for a New History Textbook, which is supported by the Nippon Kaigi.

The Japanese right wing is extending this “battleground” to the US. When the first comfort woman statue outside South Korea was erected in Glendale, California, on July 30, 2013, about 100 Japanese held a rally expressing their fierce opposition to the statue. The Japanese right wing also attempts to manipulate US public opinion by funding sympathetic American YouTubers or by keeping American journalists in their pockets.

Dezaki also brings up the responsibility of the American government. “The US has continued to force South Korea and Japan into some kind of awkward reconciliation as its primary allies in Northeast Asia, where it seeks to counter China. The remarkable similarity between South Korea and Japan’s establishment of diplomatic relations in 1965 and the Park administration’s comfort women talks with Japan in 2015 was “due to the influence of the US, which has prioritized its own interests over justice on the comfort women issue.”

Opposition from right wing boosted public press and brought out more viewers

During this film’s debut in Japan in April, it brought out more than 30,000 viewers. That was a surprisingly good turnout for an independent film, boosted by buzz from press conferences held by right-wing groups opposed to the film.

The comfort women issue ought to be seen as “a fight against racial discrimination, sexual discrimination, and fascism,” Dezaki said. “It’s very unfortunate that the Japanese government has responded to the [Supreme Court’s] recent ruling about forced labor by instituting economic retaliation. They’ve always done the same thing about the comfort women issue. Both of these issues ought to be seen as human rights issues.”

Dezaki hopes that his film will have a positive effect. “I don’t think the Japanese government’s positions are the same as what the Japanese people think. If this film helps Koreans and Japanese learn things they didn’t know about each other before, it might reduce hatred and enable productive discussion and debate,” he said.

By Yu Sun-hui, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 4Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 5US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 6[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 7All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 8[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda

- 9Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 10More South Koreans, particularly the young, are leaving their religions