hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

The quest to uncover one’s roots

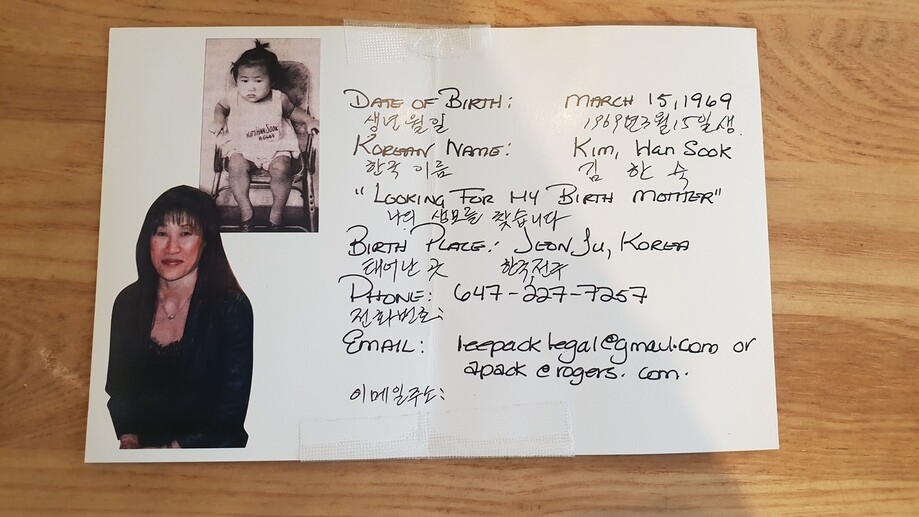

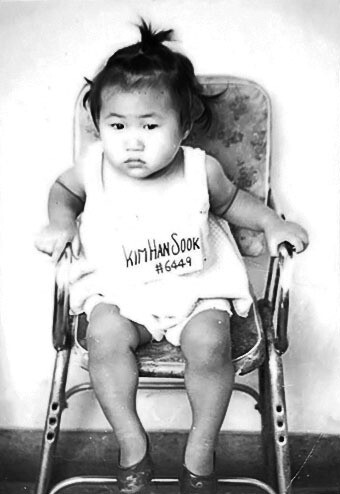

“Name: Kim Han-suk. Date of birth: Mar. 15, 1969. Domicile: unknown. Place of birth: unknown.”

In July 1969, four years after her birth, Angela Mary Lee-Pack, today 50 years old, was dropped off at Bisabeol Orphanage, in Jeonju, a city in North Jeolla Province. Two years later, Angela was adopted by the family of a Canadian veteran of the Korean War. While her adopted father was fond of her, her adopted mother was not, viewing her as a “fat Korean baby.” Even as a newborn, Angela was starved by her adopted mother and locked in the closet. She didn’t get fed until her father came home. That abuse continued for three years, until Angela was put under the care of a children’s welfare group in Canada that had learned about her situation.

In February 1976, at the age of seven, Angela was adopted by another family. But even there, life wasn’t easy for her. At the age of 15, she left her second home, where she hadn’t been given any love or attention. During her two adoptions, Angela constantly pondered her identity. She wondered who she was and how she’d come to be. She had no way to get the answers, however. Angela had serious emotional wounds, since she’d never been loved by her family. Because of those wounds, she lacked the confidence to meet her mother.

Angela had often told herself that, when she turned 50, she would go to Korea to find her birth mother. So in January of last year, she announced to her husband that she was going to do exactly that. After entering the legal profession, she’d forged a happy and stable life with her husband. Now the time had come, she felt, to show her birth mother the proud life she’d made for herself. Angela and her husband arrived in South Korea on June 4.

The only clues she had to find her birth mother were a photo of her as a child, a photo of her today, and the area where she was born. Angela decided to distribute a flyer she’d made containing all that information. Everything she knew about her identity fit onto half a sheet of A4 paper. When asked how many sheets of the flyer she’d printed, Angela said, “More than I can count. I’ve shown it to every Korean I come across.”

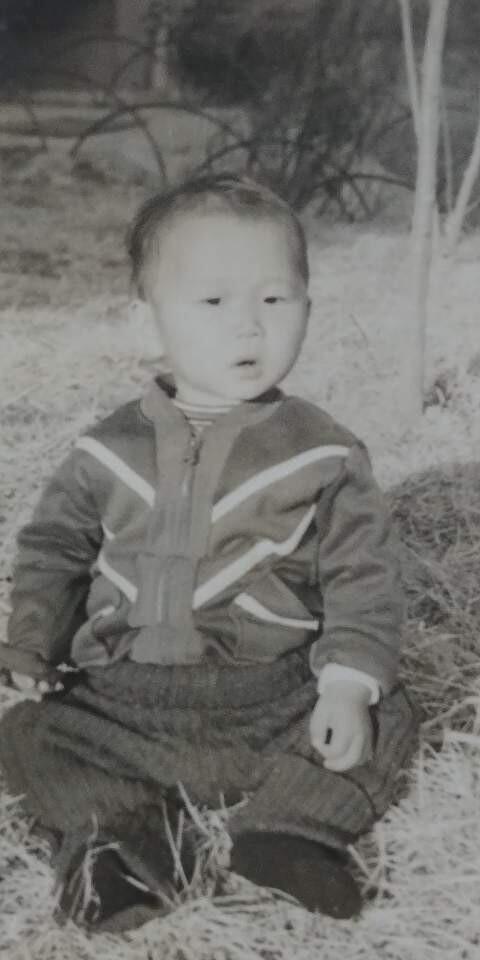

Michael Thielmann, 42, who was adopted by an American family, wasn’t able to make a half-page flyer as Angela had. He knows even less than she does about his early years. The extent of his knowledge is that he was found in Andong, North Gyeongsang Province, and (though this is less certain) that he was born on Sept. 7, 1977, and named Ahn Dong-hyeok. At the age of 15 months or so, an unidentified orphanage sent him to Andong City Hall, which passed him along to the Social Welfare Society, in Daegu. In 1979, he was sent to the US for adoption.

Since getting married to a Korean in 2006, Michael has wanted to uncover his identity as a Korean. He followed some leads at Andong City Hall, but he wasn’t able to learn anything beyond what he’d already heard from the Social Welfare Society. He only has one photo that was taken around the time of his adoption, a fuzzy black-and-white shot.

Angela and Michael had been studying Korean together for more than a year at a cultural center in Toronto. Last month, they came to South Korea as part of a “motherland tour” that’s organized each year for Korean adoptees by the Toronto-based Korean Canadian Cultural Association (KCCA). This program enables Koreans who were adopted by Canadian families to visit their country of birth.

The first place that Angela went upon coming to Korea was the Jeonbuk (North Jeolla) Provincial Police Agency. She’d hoped she might be able to find some information about her birth mother there, but the only thing they could tell her was her situation at the time of adoption, information she’d already received from Holt International Children’s Service nine years before.

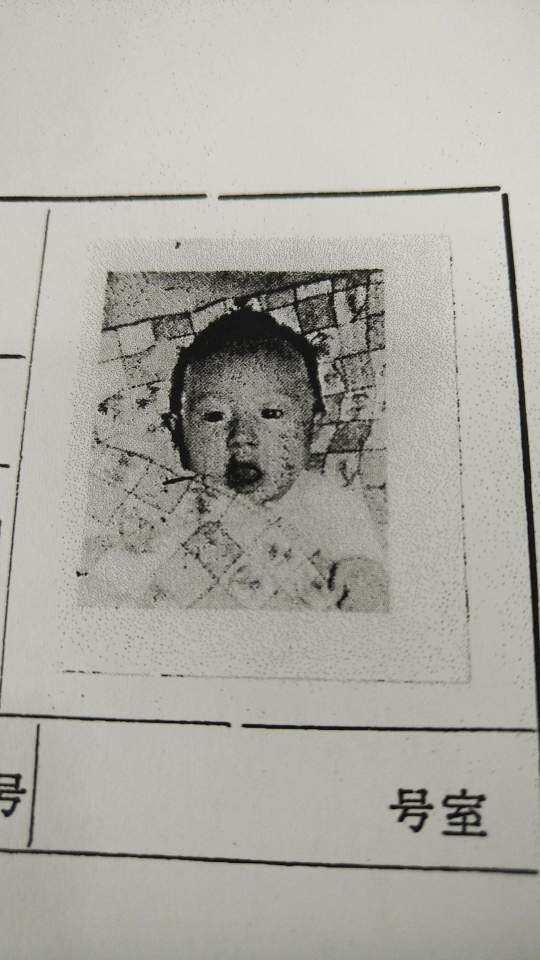

But Angela got more results elsewhere. Attached to a document obtained from Jeonju City Hall was a photo taken of Angela as a newborn, before her adoption. This document was presumably drafted when Angela was being transferred from the orphanage in Jeonju to Holt International Children’s Service. While it’s a faded black-and-white photo, it’s the only one that shows Angela shortly after birth. “Prior to that, I’d never seen a photo taken before I was adopted. Seeing this photo was amazing because it showed me how I looked as a newborn,” she said.

Courage granted by her husband’s support

Angela was able to work up the courage to look for her mother thanks to support from her husband. Chinese-Canadian Scott Lee-Pack thought that the best way for Angela to heal her emotional wounds was to find her birth mother. Angela’s life hadn’t been very easy. At the age of 23, when she was already emotionally unstable because of her two adoptions and the terrible child abuse she’d faced, Angela had a near-death experience while she was driving. Her car was crushed by a big tanker truck, which left her unconscious for two days. So Angela’s husband rolled up his sleeves and got involved in the search for her mother. He got in touch with Korean adoptees in the area and would tell any Koreans he met Angela’s Korean name and the area where she was found.

Michael visited South Korea for the first time in September 2017. “For most of my life, I’d never felt like I belonged anywhere. But when I landed at Incheon Airport and looked around, there were so many Koreans who looked similar to me. Even though I’d come halfway around the world on my own, it didn’t feel strange to me; I felt relaxed and at peace, rather than anxious,” Michael said.

Choosing to father an adopted child and give them a happy home

In 2017, Michael and his wife decided to adopt a child. Michael had grown up in a family of adoptees — his maternal grandmother, his mother, and his older sister had all been adopted. “I grew up as a happy boy in the family that took me in. I wanted to adopt a child like myself and give them that happy home,” he said.

“In fact, I’d already been disappointed once before, back in 2006, when I learned how hard it would be to find my mother, and I’d given up after that. But I didn’t want to pass on to my child that disappointment, and the anxiety resulting from forfeiting my identity as a Korean. I came to Korea because I wanted to be a decent father, both psychologically and emotionally.”

That winter, Michael had a DNA test done at the Seoul Metropolitan Police Agency. He also paid a visit to Andong City Hall, but they didn’t have any information besides what his adopted family had received at the time of his adoption. Even that was a three-page document that a social worker had written, based on the testimony of people who knew Michael before he was sent to the US for adoption. “I couldn’t find any records about myself from before December 1978, when I was transferred to Andong City Hall. The records say I’d been dropped off at an orphanage by my mother at the age of 15 months, but it’s not certain that she was actually my mother,” he said.

This month, Angela and Michael will be returning to Toronto. Because the information they possess is so limited and tenuous, their visit to South Korea has shown them the difficulty of finding their birth mothers. That said, they insist that their visit hasn’t been a frustration or a failure.

“Korea is a place that feels peaceful to me. While being here, I haven’t had to try to act white. It was time when I felt peace of mind,” Michael said.

“During my four weeks in Korea, I’ve learned things about myself for the first time. I’ve learned the reason for all the things I do. For example, I’ve had trouble with the pronunciation of the English ‘r’ for my whole life. Talking to Koreans here, I’ve figured out why that pronunciation has been so tricky for me,” Angela said with a smile.

When asked what they’d want to tell their mother, given the chance to meet her, both Angela and Michael were silent for a while. When Angela finally spoke, she said, “I still don’t know what I would say if I met my mother. I don’t want to ask why she made that choice; whatever the reason, I understand. The only thing I would like to know is when and how I came to be.”

“I want to tell her ‘it’s okay,’” Michael said. “If she doesn’t want to see me, that’s okay. Even if I don’t get to see her, my greatest desire is to tell her it’s okay.”

By Oh Yeon-seo, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Caption:

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 1[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 2Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 3In rejecting statute of limitations defense in massacre case, Korean court faces up to Vietnam War a

- 4Historic court ruling recognizes Korean state culpability for massacre in Vietnam

- 5“Those souls can rest now”: Vietnam massacre survivor reacts to Korean court win

- 6[Editorial] Verdict on Korea’s massacre in Vietnam a first step in atonement

- 7Ruling on Korean atrocity in Vietnam comes 23 years after Hankyoreh 21’s exposé

- 81 in 3 S. Korean security experts support nuclear armament, CSIS finds

- 9[Interview] Continuing the fight for victims of civilian massacres during Vietnam War

- 10Korea’s atrocities in Vietnam, in the words of those who saw and survived them