hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Correspondent’s column] At the heart of tensions in S. Korea-Japan relations

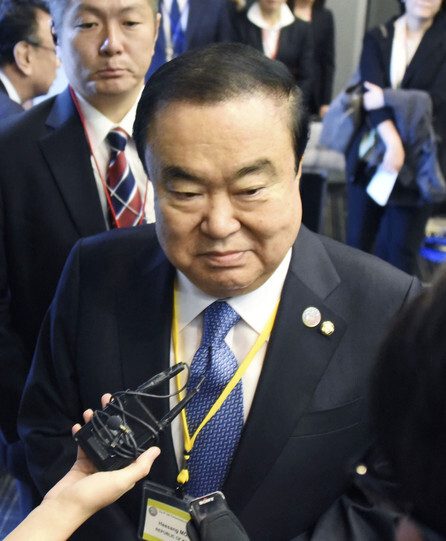

On Nov. 5, South Korean National Assembly Speaker Moon Hee-sang gave a talk in a classroom at Waseda University in Tokyo. Attendees had to undergo an inspection of their belongings. Police could be seen positioned all around the school. This seemed to be a reflection of negative Japanese public opinion toward Moon following a February interview where he suggested that the Japanese military comfort women issue could be resolved with an apology from the Japanese emperor. Indeed, when Moon referenced his earlier remarks during his talk, saying that he “would like to apologize if I upset any Japanese people,” one audience member showed, “Lower your head and apologize before [then] Emperor [Akihito].”

Visiting Japan at a time when the mood toward him was not positive, Moon presented a proposal on what has recently been the most sensitive issue between the two sides: survivors of forced labor mobilization. He suggested that South Korea enact a law to create a fund with voluntary contributions from South Korean and Japanese companies and members of the public. His idea was to head off future legal action over historical issues between the two sides through legislation that encompassed both the forced labor mobilization and the comfort women issues.

I do believe that Moon’s proposal came after serious consideration of what feasible means exist for ending the chill in South Korea-US relations. During the talk, he said, “I am aware I could end up facing criticism from the public of both countries for not living up to their standards.”

But there are some worrying aspects of Moon’s proposal. The first concerns the nature of the fund. During a Nov. 1 joint meeting of the two sides’ respective bilateral parliamentarians’ unions, Takeo Kawamura, chief secretary of the Japan-South Korea Parliamentarians’ Union, said it would be “acceptable to create a fund for future-oriented things, for energy and new industries.” His remarks suggested Japan would only consider it if it were intended as an “economic cooperation fund” that was not recognized in any way as compensation for forced labor. The survivors, for their part, would never support the fund if it were turned into something that completely repudiates its nature as compensation for forced labor.

Second, because it would be based on “voluntary” contributions, there would be no means of “forcing” the Japanese companies responsible for forced mobilization to participate. These companies were the ones who perpetrated forced mobilization, and a fund that does not require their participation loses its rationale for existing. Even if Japanese companies that engaged in forced mobilization were to take part in the fund, they could easily claim that they were not doing so for reasons related to the forced mobilization issue. Third and most important is the question of whether there was any dialogue with the survivors and whether this is a victim-centered plan.

Unless the South Korean government reverses its decision, the South Korea-Japan General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA) ends at midnight on Nov. 23. The US government is pressuring Seoul to extend the agreement. The Japanese government has also been adamant in claiming that Japanese companies must not agree to compensation for forced mobilization, maintaining that the South Korean Supreme Court ruling was in violation of the Claims Settlement Agreement signed by the two sides in 1965. Barring some dramatic deal being reached, assets seized from Japanese companies following the Supreme Court ruling are to be liquidated early next year. When this happens, the Japanese government is very likely to implement some new retaliatory action, characterized officially as a “resistance measure.” The situation facing South Korea is a serious one.

At the same time, it needs to avoid allowing these circumstances to push it into a hasty “solution” that repeats the same mistakes as the comfort women agreement reached by the South Korean and Japanese governments in 2015. Referring to the comfort women agreement in his talk, Moon said, “I think it never was realistic to have an agreement that the victims themselves did not support at all. The essence of a resolution to the comfort women issue lies in restoring the dignity and honor of the victims and healing their wounds.” At its root, the same is true for a resolution to the forced mobilization issue: it needs to be about restoring the victims’ dignity and healing their wounds.

By Cho Ki-weon, Tokyo correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 4Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 5Up-and-coming Indonesian group StarBe spills what it learned during K-pop training in Seoul

- 6The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan

- 7Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 8S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 9Ferry accident likely due to whale; 1 killed

- 10[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?