hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Reportage] Possible remains of Korean laborers excavated in Okinawa

On the morning of Feb. 9, a man took a human vertebra out of aluminum foil and placed it on a rock in a parking lot. Then he wrapped the bone back up in the foil and set it on the rock.

Ahn Gyeong-ho, secretary-general of the April 8 Unification and Peace Foundation, briefly removed the foil from other objects — not only vertebra, but also bullets and clothing used by American soldiers, buckles (presumably used with backpacks), and even old Japanese coins.

This parking lot — in the sleepy seaside village of Kenken, in the town of Motobu, in the Kunigami District of Japan’s Okinawa Prefecture — is the place where two Koreans who were drafted to work for the Japanese army during World War II are believed to be buried. On Sunday, Ahn was one of a group of people from South Korea, Okinawa, the Japanese mainland, and Taiwan who had gathered to begin excavating their remains.

The bones, shells, and other items turned up in a preliminary dig on Feb. 7, before the joint excavation began. The group focused their digging on the place where the vertebra had been found.

Okinawa was the only part of Japan’s home islands that saw major ground combat during World War II. It’s estimated that some 200,000 people, including Japanese soldiers, Okinawan civilians, and Korean and Taiwanese conscripts, died during the campaign there.

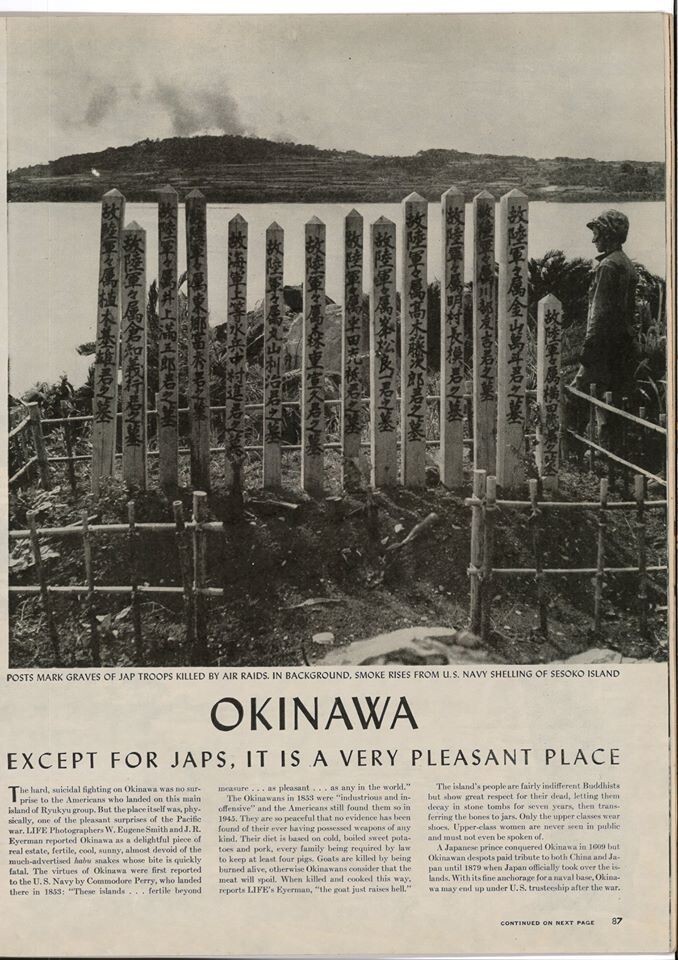

The excavation of Korean remains there is a rare occurrence. The project was sparked by a photograph printed in the US magazine “Life” in May 1945. In the photo, an American soldier is gazing at the ocean next to wooden grave markers bearing inscriptions in kanji, the Chinese characters used in Japan. Two of those names (given their Chinese reading) are “Geum San Man Du” and “Myeong Chon Jang Mo,” presumably Japanese-style names that Koreans were forced to adopt during Japan’s colonial occupation.

After cross-referencing those names with a list of Koreans conscripted during the war, Okinawan activists confirmed that the graves belonged to individuals named Kim Man-du and Myeong Jang-mo, who had been drafted as workers for the Japanese army. At the time of their death, Kim was 23 years old, and Myeong was 26.

According to Japanese military records, the two men boarded the Hikosan Maru, a ship that had been requisitioned as a transport ship for the Japanese military. A large number of people died aboard that ship in a US air raid on Jan. 22, 1945. The 14 individuals whose names appear on the grave markers include the captain of the Hikosan Maru, soldiers, and civilians working for the military.

It’s unclear whether the vertebrae unearthed on Feb. 7 belong to any of these 14 individuals. It’s not even clear whether they’re Korean. “The maturity of the bones suggests the deceased was no more than 18 or 19 years old,” said Park Seon-ju, professor emeritus of archaeology and art history at Chungbuk National University and an expert on the excavation of human remains.

“The bones were found at a depth of 4m, but soil was piled up here after the war. Given the depth of the dig, they might not belong to the 14 people [on the grave markers],” Park added.

Another factor driving the excavation project is the fact that villagers identified the specific spot where the victims’ remains had been buried after their cremation. The excavated bones show no signs of cremation, however.

“Some of the villagers say the bodies were cremated, while others say they were buried intact,” said Fukiko Okimoto, one of the leaders of the excavation project.

According to Okimoto, it’s impossible to say for sure whose bones they are.

In order to make a positive identification, the bones would have to contain enough DNA for testing.

“We can’t just ignore these remains. Even if too much time has passed for the remains to be returned to their loved ones, we need to restore their dignity as human beings who once walked the earth,” Okimoto emphasized.

A ceremony for the departed was held before the excavation began on Sunday. The people gathered expressed their hope that the spirits of the remains would return home. Across the waves, I could see Sesoko Island, looking much the same as it had in that 75-year-old photo.

The excavation will continue through Feb. 11, overseen by a joint action committee comprising a South Korean NGO called Stepping Stones to Peace and a Japanese group organized to “send home” the human remains at Kenken.

By Cho Ki-weon, Tokyo correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0416/8917132552387962.jpg) [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces![[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0416/8317132536568958.jpg) [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

- [Guest essay] At only 26, I’ve seen 4 wars in my home of Gaza

- [Column] Syngman Rhee’s bloody legacy in Jeju

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- 2Faith in the power of memory: Why these teens carry yellow ribbons for Sewol

- 3[Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- 4[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- 5K-pop a major contributor to boom in physical album sales worldwide, says IFPI analyst

- 6How Samsung’s promises of cutting-edge tech won US semiconductor grants on par with TSMC

- 7Korea ranks among 10 countries going backward on coal power, report shows

- 8Final search of Sewol hull complete, with 5 victims still missing

- 9[Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- 10Exchange rate, oil prices, inflation: Can Korea overcome an economic triple whammy?