hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] How Trump’s anti-China narrative actually helps Beijing

Trump and Xi seem hardline upfront but have actually worked to maintain status quo

If I had to point to a day when the absolute power of Chinese President Xi Jinping trembled, it would be Feb. 6, 2020.

That was the day the doctor Li Wenliang died in Wuhan, Hubei Province, which was under lockdown as China battled the chaos and pain caused by COVID-19. The first reports that Li had died around 9:30 pm were immediately suppressed by state censors. The official announcement didn’t arrive until 3 am, deliberately delayed by authorities worried about public outrage.

Li had been the first to sound the alarm about the COVID-19 outbreak, at the end of December 2019. That led to his arrest and punishment by the Chinese police on the grounds that he was spreading rumors; later, he was himself infected and eventually succumbed to the disease. For some time, Li’s final message — “I think a society should not have just one voice” — and similar ideas reverberated throughout China. The dead doctor had shaken the authority of the living president.

Xi Jinping’s salvation came in the person of US President Donald Trump. Just as the COVID-19 outbreak in China was stabilizing in early March, pandemonium was breaking out in the US. Reports about the awful situation in the US, caused by Trump’s irresponsibility and incompetence, underlined the comparative advantage of Xi’s leadership, which had brought the situation under control by locking down Wuhan and its 11 million inhabitants for 77 days.

As Trump repeatedly criticized China in an attempt to shift the blame for his poor handling of the outbreak, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) stood its ground, stirring up patriotism at home. When Trump gave airtime to a conspiracy theory about the coronavirus originating in a Wuhan laboratory, Chinese diplomats responded with rumors of their own about US military athletes spreading the virus.

The Chinese authorities doubled down on propaganda, including the claim that China had saved the world through its sacrifice, and provided masks and other disease control equipment to other countries to reinforce its self-proclaimed status as savior. Articles published after Li’s death that had criticized the government and advocated free speech were scrubbed from the internet, and citizen reporters who had tried to share the truth about Wuhan were arrested or went missing. The feckless responses and horrific scenes in the US and other Western countries were a dramatic case study reinforcing the conclusion that the CCP, as authoritarian and overbearing as it might be, was eminently competent.

The two pillars propping up the CCP’s legitimacy are economic growth and patriotism. Since nearly the entirety of China was put on lockdown for nearly two months to stop COVID-19, the country posted an economic growth rate of -6.8% in the first quarter of the year. But even before the outbreak, dark clouds had been gathering over the Chinese economy: a falling economic growth rate, local government debt, and other financial woes. During this year’s National People's Congress, China didn’t even dare to offer a target economic growth rate. The growth rate rebounded to 3.2% in the second quarter, but that was driven by large-scale government investment in its “new infrastructure” initiative of building infrastructure for 5G and AI, and Chinese exports, domestic demand, and employment are still shrouded in uncertainty.

China leans on patriotism to overcome economic anxietyAs economic anxiety increases, China leans more heavily on the other pillar of patriotism. The more Trump tries to blame China for his own failure in dealing with COVID-19, the more he enables Xi to dominate public opinion at home with an appeal to patriotism in a showdown with the US. The relationship between the two leaders is one of “hostile symbiosis,” with each desperately in need of the other. Just as Trump argues that he should be reelected because he’s better equipped to put pressure on China, Xi also brags that China has grown strong enough under his governance to speak up to the US and confront it as an equal. That’s how Xi makes use of Trump.

The two leaders first met in a summit at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort, in Palm Beach, Florida, on Apr. 6, 2017. Trump had run for president under the mantra of “America first,” pledging to reclaim the jobs and economic advantage that, in his view, had been handed over to China. While Trump and Xi were dining after their summit, Trump disclosed that dozens of Tomahawk cruise missiles had just been launched at Syrian government air bases. The surprise announcement was calculated to catch Xi off guard.

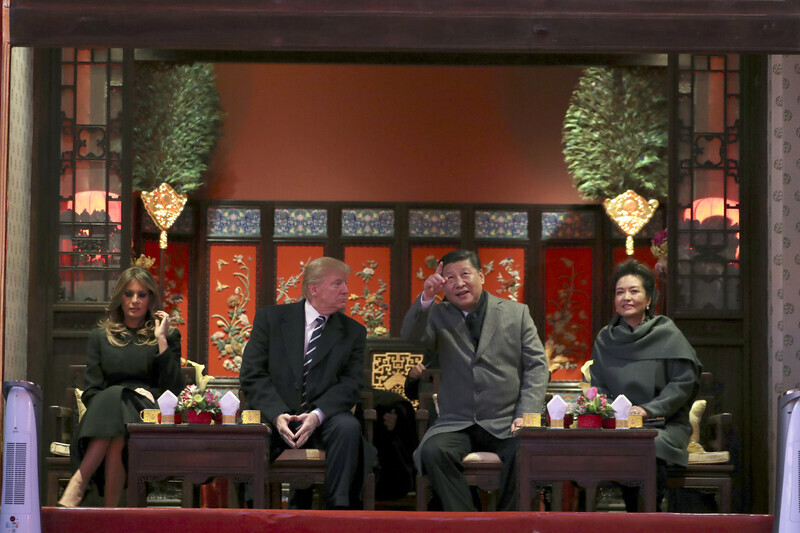

That November, Xi cleared out the Forbidden City in advance of Trump’s visit. This was extraordinary hospitality for the American president on what Beijing called a “state visit plus.” But at the same time, it was also Xi’s way of underscoring that China was an equal of the US through the “imperial protocol” of hosting Trump at the Forbidden City, soon after Xi had abolished term limits and consolidated his uncontested control over China.

In early 2018, soon after returning from his opulent visit to Beijing, Trump initiated a trade war with China. He began raising tariffs to counter China’s trade surplus with the US while also taking aim at Made in China 2025, a Chinese policy initiative that seeks to develop cutting-edge technology and bolster technological self-sufficiency. The US also placed pressure on South Korea, Japan, and the countries of Europe to keep Chinese company Huawei out of 5G networks around the world.

This year, the US has not only been blaming China for the COVID-19 outbreak but also threatening a “decoupling” that would shove China out of the world’s financial and manufacturing systems. Trump recently issued an executive order that ends special treatment for Hong Kong and signed a bill that sanctions banks that do business with Chinese bureaucrats who were involved in the enactment of the Hong Kong national security law; these could be the first shots in a “financial war” between the two countries.

US unlikely to deliver serious blow in trade war with ChinaBut despite the US’ shrill attacks on China, the Trump administration is unlikely to make any moves that would deliver a serious financial or economic blow to China before the presidential election in November. John Bolton, former White House national security advisor, revealed in recently published memoirs that Trump had earnestly asked Xi during the G20 summit in Osaka in June 2019 to import more American soybeans and wheat to help him get reelected.

In public, Trump was leaning hard on China, but behind the scenes, he was making free-handed deals. In the phase one trade deal that the US and China reached at the beginning of this year, China agreed to buy US$200 billion worth of American farm produce and other goods. Trump’s prospects of winning reelection greatly depend on whether China makes those purchases as promised, which in effect gives China major leverage over Trump.

COVID-19 has increased Trump’s dependence on XiThe COVID-19 outbreak has pushed Trump into a corner, putting him in even greater need of the Chinese help to turn the economy around. The US’ response to China’s enactment of the Hong Kong national security law is political showmanship, designed to look tough but actually reflecting caution. The Trump administration considered restricting the US dollar supply to Hong Kong but ultimately shelved the idea. Attacking the Hong Kong dollar peg — which fixes the currency at 7.75-7.85 Hong Kong dollars to the US dollar — would deliver a devastating blow to the financial system both in Hong Kong and in China, but it would also cause serious harm to American companies and financial capital in Hong Kong.

The US and China will no doubt continue their military standoff in the South China Sea and their bickering over the issues of Hong Kong and China’s treatment of the Uighur minority in Xinjiang, but the US won’t decisively target Chinese weak points at least until the US presidential election.

But the new “cold war” between the US and China could enter a more perilous phase after the US presidential election this year. China’s concern is that if Trump is defeated and a Democratic administration is formed under Biden, the US government’s strategy of containment will grow much more sophisticated. Xi’s government is operating on the assumption that Trump’s reelection would serve China’s interests more than Biden’s.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who has been in the vanguard of the assault on China, met with China’s top diplomat Yang Jiechi in Hawaii on June 17 for two days of closed-door dialogue. During that meeting, Pompeo and Yang seem to have reached some kind of secret truce. This signals that both the US and China are taking a hard line in public but actually want to maintain the status quo for now.

The Chinese are fully aware that a consensus has formed in the US about the need to contain China, a rare point of bipartisan agreement between Democrats and Republicans. China can keep Trump’s anti-Chinese campaign from getting out of hand by agreeing, for example, to buy farm produce. What Xi and other Chinese leaders are worried about is that, with the Democrats in power, the US would hit China harder in the areas of finance, cutting-edge technology, and human rights, and would bolster alliances that Trump has undermined to complete China’s encirclement.

Trump’s reelection would repel traditional Washington’s alliesIf Trump is reelected, on the other hand, countries such as Germany and France will contemplate parting ways with the US. China is no doubt framing a strategy for exploiting that potential so as to engineer a geopolitical realignment. The “cooperation agreement” that China and Iran will apparently be signing soon is part of the groundwork for that strategy.

Given the evident limitations of the US-led world order, China has used its Belt and Road Initiative (also known as the New Silk Road) to experiment with a new international order, or at least an order for China’s sphere of influence. Xi’s government has declared that China will go down its own path and no longer abide by the systems and ideas of the Western world. Hu Jintao carefully pretended to follow norms under Deng Xiaoping’s concept of “tao guang yang hui” (literally meaning “hide brightness and nourish obscurity”), but now his successor Xi Jinping has adopted a more aggressive foreign policy under the banner of the “great resurgence of the Chinese people.”

Intensifying international pressure only pushes China to further demonstrate its strengthAs the US spins its wheels, China has been exploiting the power vacuum to take audacious action in a range of border conflicts in Hong Kong, Xinjiang, the South China Sea, Taiwan, and India. Its moves appear aimed at eliminating all potential threats and weaknesses before the US can regroup and resume encirclement. When China rammed through the national security law in Hong Kong, it was trying to nip in the bud any possibility of the US undermining China by way of Hong Kong or of the Hong Kong democracy protests affecting the mainland.

Intensifying international criticism only pushes China to make further demonstrations of its strength. The Chinese leaders are stubbornly convinced that any hint of giving ground or compromising would give the US a pretext to hit China in its weak spots and give domestic discontents an opportunity to challenge Xi’s authority. The three fundamental factors that I think have forged the Xi system are the lessons learned from the collapse of the Soviet Union, the trauma of the Cultural Revolution, and China’s panic about its confrontation with the US. As China repeatedly attempts to confirm the “revival of the Chinese empire” through strength, anxiety is spreading among its neighbors.

By Park Min-hee, editorial writer

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/8317138574257878.jpg) [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father![[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms? [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/3617138579390322.jpg) [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 2Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 3Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76

- 4[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 5[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 6Opposition calls Yoon’s chief of staff appointment a ‘slap in the face’

- 7Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan

- 8New AI-based translation tools make their way into everyday life in Korea

- 9[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 10[Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?